Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to be able to thank the many people who have helped see this book into print. Their assistance has added immeasurably to the value of this work; any faults that remain are mine alone.

The University of California at Berkeley introduced me to wonderful scholars (some now dispersed to other places) who helped start this project in the right direction and, more important, taught me how to ask the questions I needed to keep it going on my own: Celeste Langan, Sharon Marcus, Colleen Lye, Catherine Gallagher, and Lydia Liu. Mai-Lin Cheng and Asali Solomon remain trusted sounding-boards and true friends. I also thank the University of California for a Dissertation-Year fellowship and the Townsend Center for the Humanities for allowing me to participate as a year-long fellow and showing me what interdisciplinary conversation could look like.

At the University of Missouri, the English Department as a whole, and especially my colleagues in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century studiesNoah Heringman, George Justice, Devoney Looser, and Nancy Westhave offered support, advice, and friendship in equal measure. Sam Cohen, Joanna Hearne, and Donna Strickland read every page of this book and made every page of it better. The students, both graduate and undergraduate, have helped me tremendously both by taking generous interest in my work and by sharing their interests with me. The University of Missouri Research Board and Research Council supported a years leave and a summers visit to London archives, respectively; both were indispensable to the progress of this manuscript.

For their comments on and support of my work, I wish to thank the members of the Dickens Project, Ross Forman, Dane Kennedy, Douglas Kerr, Julia Kuehn, Peter Logan, Teresa Mangum, Erika Rappaport, and Philip Stern. David Hanson published an earlier and partial version of Chapter 2 in Nineteenth-Century Studies and gave valuable editorial feedback. I also thank the library staffs who have helped me acquire the necessary materials for this study, in particular all the library staff at the University of Missouri, as well as the Bancroft Rare Book Library, the British Library, the Wellcome Library, the Lindley Library of the Royal Horticultural Society, and the Library and Archives at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

At Stanford University Press, I want to thank especially Emily-Jane Cohen, who shepherded this book through its long development process, and Sarah Crane Newman, attentive to every detail. I also want to thank the anonymous readers of the manuscript whose suggestions changed this book in uniformly good ways.

My family has remained ever patient with the demands of this project. I want to thank all of them, especially Claire and Ed Stiepleman, kindest of in-laws; Lily Shih, Witt Monts, Gabriel Monts, and Serena Monts, best of cousins; and of course my parents, Margaret and Raymond Chang, who showed me how to write and to teach long before I realized that I would want to do both of those things. I have since realized both how hard and how wonderful it is to follow their shining examples. Most of all I must thank my children, Isaac, Ezra, and Jacob, and my husband, Peter, for love and companionship beyond the bounds of words.

Conclusion

At the end of the nineteenth century, China was understood to become ever more alienated from the conditions that made it visible to British eyes. Realignments among the global powers changed the place of China in the British imagination. Japan and, later, Africa took up Chinas role in the minds of many modern critics as the preeminent visual and geographical counterpoints to Euro-American visual and literary modernism. Yet even as those influences now seem to outweigh Chinas, they could not have done so without the foundational structure that China provided.

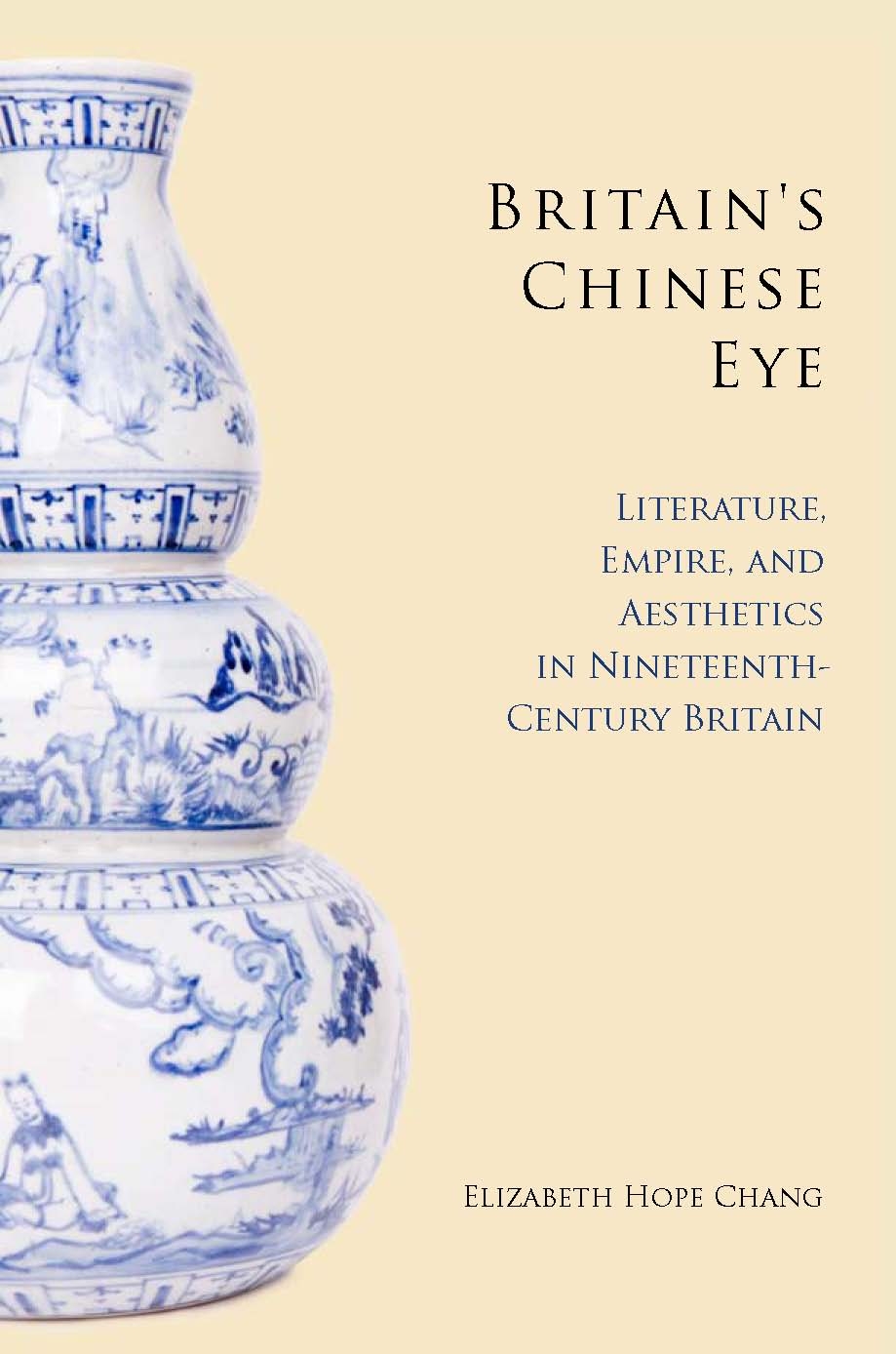

This book has followed both British celebrations and British repudiations of Chinas familiar exotic across the nineteenth century with the simple contention that such receptions mattered greatly in the history of British visuality. They mattered as opposing examples that helped define by antithesis the capacities of the British visual and narrative realdefinitions that have been the subject of this book. They continued to matter, albeit largely implicitly, when the revolutions of modernism revised visual realism and claimed supposedly foreign and antithetical aesthetic terms as their own founding conditions. And they matter still. A sense that the Chinese somehow see differently, and that certain differences in visual representation can therefore be identified specifically as Chinese, makes unspoken substance for current rhetorical formations that describe relative differences between China and the West in essentialized terms. Although differences in modes of perception are now the terrain of cognitive neurologists as well as writers and artists, this broadening of inquiry has not altered the initial parameters of the questioning.

When I say that such receptions mattered, I mean that very literally. Material objects, physical spaces, and the narrative evocations of that materiality and spatiality explained Chinese visual difference to British observers through all the permutations of visual engagement: looking, being looked at, seeing others looking, and directing others how to look in turn. These engagements change with changing economic conditions; production and trade make objects available to view, but they also make subjects capable of seeing them in meaningful ways. When Lord Macartney entered the Qing emperors pleasure grounds to partake of their rural vicissitudes, he did so under very different circumstances than his secretary, John Barrow, who was reduced to peeking over the edge of the garden wall. The political authority that granted Macartney a clearer perspective on the gardens views, however, expired with the failure of his mission; the narrative authority that Barrow gained as author of the widely read Travels in China continued onward throughout the century. Thus while the gap between Barrow and Wordsworth is broadand the gulf between Barrow and Whistler (to take one of many possible examples) nearly unbridgeableit is their shared interest in Chinas representational (rather than direct) effects that justify this studys connections.

A precondition of this study has been the sense that these arguments can be generalized beyond the Chinese example; by thinking about how racial difference is imagined to make certain differing kinds of perception possible, we can also understand how other categoriesclass, gender, sexuality, and morecan be imagined to do the same thing. But I want to insist upon the specific value of China as an example. Economic histories of the past decades have shown Chinas role in the globalization of the world economy to occur both earlier and more significantly than was previously believed. Even as Britons were following the story of Chinas resounding defeat in the First and Second Opium wars, they were filling their lives with the material effects of Chinas economic significance. Though some of Chinas emblematic productstea, porcelain, and even opiumwere by the end of the century produced domestically or in British colonies, they retained their symbolic status as pieces of China.

Whistlers painting Purple and Rose: Lange Leizen of the Six Marks, discussed in Chapter 2, makes a useful point to return to here in considering how we ought to understand Chinas place in Victorian creative consciousness. Critical reception of Whistlers painting can be compared with the far more famous and more controversial scene of modeling of foreign influence demonstrated in a later artwork: Pablo Picassos Les Demoiselles DAvignon (1907). In Picassos Cubist masterpiece, two of the five nude prostitutes depicted wear faces deeply evocative of African tribal masks. How to talk about Picassos use of these artifacts, which may be based on objects he saw during a memorable visit to the Muse dEthnographie du Trocadro in 1907, is a problem that has consumed art critics for many decades. On the other hand, questions about what the Chinese objects in Purple and Rose mean to Whistler are only beginning to be asked by postcolonial scholars. Yet much of the inquiry that scholars have directed to Picassos masterwork, in particular Simon Gikandis recent probing study, can be aimed at Whistlers work as well.

![Harvie Christopher - Nineteenth-century Britain: a very short introduction ; [in memorian Colin Matthew]](/uploads/posts/book/137651/thumbs/harvie-christopher-nineteenth-century-britain-a.jpg)