ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Chinese dress has gone through many changes since my first small book was published in 1987. At that time, China was emerging from the tumultuous years of the Cultural Revolution (196676), controlled and driven by Mao Zedong. His eventual successor Deng Xiaopings open-door policy allowed the country to open up again to the world, with, inevitably, Western influences filtering in via the media and foreign visitors. In Hong Kong, too, changes which began with the booming economy in the late 1970s saw long-established villages and market towns replaced by New Towns, each populated by more than half a million people.

When I arrived in Hong Kong in 1973, villagers in the New Territories were still dressed in the traditional shan ku , the ubiquitous black pajamas worn for centuries throughout China. In contrast, across the border, on my first visit to Guangzhou two years later, during the Cultural Revolution, I found everyone attired in blue or green Mao suits. It was impossible to imagine that only seventy years earlier, mandarins clad in sumptuous dragon robes were swept along in sedan chairs while their womenfolk, in richly embroidered gowns, tottered about on tiny bound feet.

Today, except in remote regions and areas populated by the minority groups, the dress of the vast majority of Chinese is indistinguishable from that of any other community around the world. Western dress has become the norm, ranging from top French and Italian designer labels purchased in up-market boutiques in Shanghai or Beijing to market stalls selling mass-produced goods, including designer imitations.

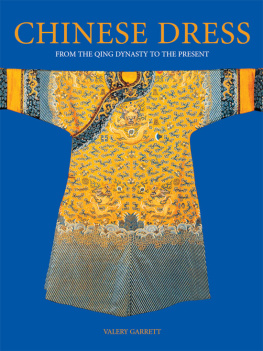

Although this book covers Chinese dress from the Qing dynasty (16441911) to the present day, with the exception of the many minority groups, the emphasis is on the dress of the twentieth century as reflected in the many wide-sweeping changes that occurred in Chinese society and culture. The dress of imperial China has already been well documented by costume historians like Schulyer Camman, John Vollmer, and Verity Wilson, and in my earlier work. I have always been more concerned about what ordinary people wore, stimulated initially by my interest in the farming and fishing groups of Hong Kong during the 1970s and 1980s where I was able to carry out fieldwork. At this time, life in China was too disruptive and the country off-limits to researchers.

So the start of a new millennium seemed a good a time to look back, over three centuries, and especially the past twenty years, to reflect on what has changed, and how much has stayed the same. Despite the universal influences of technology little dreamed of in the 1980s, I am glad to see that ancient customs which lay dormant during the turbulent times of the Cultural Revolution have been revived. Family connections are still important, and the lunar calendar continues to be observed with festivals carried out with fervour. Thousand of years of traditions survive and even thrive into the twenty-first century.

Many friends and collectors have helped in the gathering of information for this book. I have also found the work of Andrew Bolton and Sang Ye on the second half of the twentieth century in China most helpful. I would especially like to thank long-time friends and collectors Chris Hall, Teresa Coleman, and Judith and Ken Rutherford for their generous loan of items. Others who have assisted along the way are my husband Richard, Ian Dunn, Peter Gordon, Dr James Hayes, Dr Peggy Lu, Gail Taylor, John Vollmer, Vera Waters, Christina Wong Yan Chau, Linda Wrigglesworth, and not forgetting Holly. My editor, Noor Azlina Yunus, has been a constant source of support and encouragement. To all I give my sincere thanks.

Most of the photos and illustrations come from my collection, acquired over the past thirty years of living in Hong Kong, and from making very frequent visits to China. In Hong Kong, I was able to visit remote villages in the rural New Territories on a regular basis, where I photographed the villagers still wearing traditional dress and who generously donated or offered items for sale. A large proportion of these garments and accessories eventually formed the Valery Garrett Study Collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, for the benefit of future researchers. In China, my visits to dealers, individuals, street markets, and curio stores proved fruitful and were a wonderful way of getting to know the country and its people. Three decades of collecting have brought untold pleasures and, most of all, treasured friends.

All photographs and illustrations are in the collection of the author, except where indicated below. Photographs in this book were provided by, or reproduced with the kind permission of the following individuals or organizations. Care has been taken to trace and acknowledge the source of illustrations, but in some instances this has not been possible. Where omissions have occurred, the publishers will be happy to correct them in future editions, provided they receive due notice.

Hugh D. R. Baker, London, UK: Fig. 364

Frances Bong, Hong Kong, SAR: Fig. 453

LuLu Cheung, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 509, 510

China Tourism Photo Library, Hong Kong, SAR: Fig. 384

Don Cohn, New York, USA: Fig. 172 (left)

Teresa Coleman Fine Art, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 20, 24, 81, 9597, 191, 201, 203a, b, 218221 (right), 234, 376 (top left, top right), 408, 409

T. R. Collard: Fig. 39

Niels Cross, UK: Fig. 429

The Field Museum, Chicago, USA: Fig. 9

Valery Garrett/Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, SAR: Fig. 242

Valery Garrett/Hong Kong Museum of History, Hong Kong, SAR: Fig. 362

Chris Hall Collection Trust, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 17, 19, 21, 22, 28, 31, 50, 63, 70, 79, 80, 87, 92, 94, 118, 121, 123 (bottom right), 133, 136, 146, 147, 153, 154, 156, 169, 171 (left), 174 (right), 188, 192, 208, 243, 246, 247, 283, 285, 287290, 299, 305, 374, 419, 421, 422, 449, 450, 452, 462, 463

James Hayes, Sydney, Australia: Fig. 253

Hong Kong Trade Development Council, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 502, 503

Ragence Lam/Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong SAR: Figs. 505, 506

Library of Congress, Washington, USA: Fig. 237

Keith Macgregor, UK: Fig. 341

Judy Mann, Hong Kong, SAR: Fig. 504

Nanjing Museum, Nanjing, PRC: Fig. 1

National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China: Figs. 14, 59, 61

Palace Museum, Beijing, PRC: Figs. 5, 7, 15, 26, 41, 55, 75, 77

Public Records Office, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 254, 316, 333

Royal Ontario Museum ROM, Toronto, Canada: Fig. 16

Judith Rutherford, Sydney, Australia: Figs. 195, 477

Ken Rutherford, Sydney, Australia: Fig. 12

Sothebys Picture Library, London, UK: Fig. 52

South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 324, 388

Vivienne Tam, New York, USA: Figs. 444, 507, 508

Peter Tang Wing Tai, Macau, SAR; Fig. 129

Shanghai Tang, Hong Kong, SAR: Figs. 511, 512

Murray Warner Collection of Oriental Art, University of Oregon Museum of Art: Fig. 11

Vera Waters, Hong Kong, SAR: Fig. 501

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK: Figs. 6, 56

Linda Wrigglesworth, Ltd. London, UK: Figs. 49, 69, 187, 241

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, William,A Group of Chinese, Habited for Rainy Weather, The Costume of China Illustrated in Forty-eight Coloured Engravings , London: Miller, 1805.

Ball, J. Dyer, Things Chinese: Being Notes on Various Things Connected with China, London: Low, 1900; 5th edn published Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh, 1925; reprinted Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Berliner, Nancy Zeng, Chinese Folk Art , Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1986.