CONTENTS

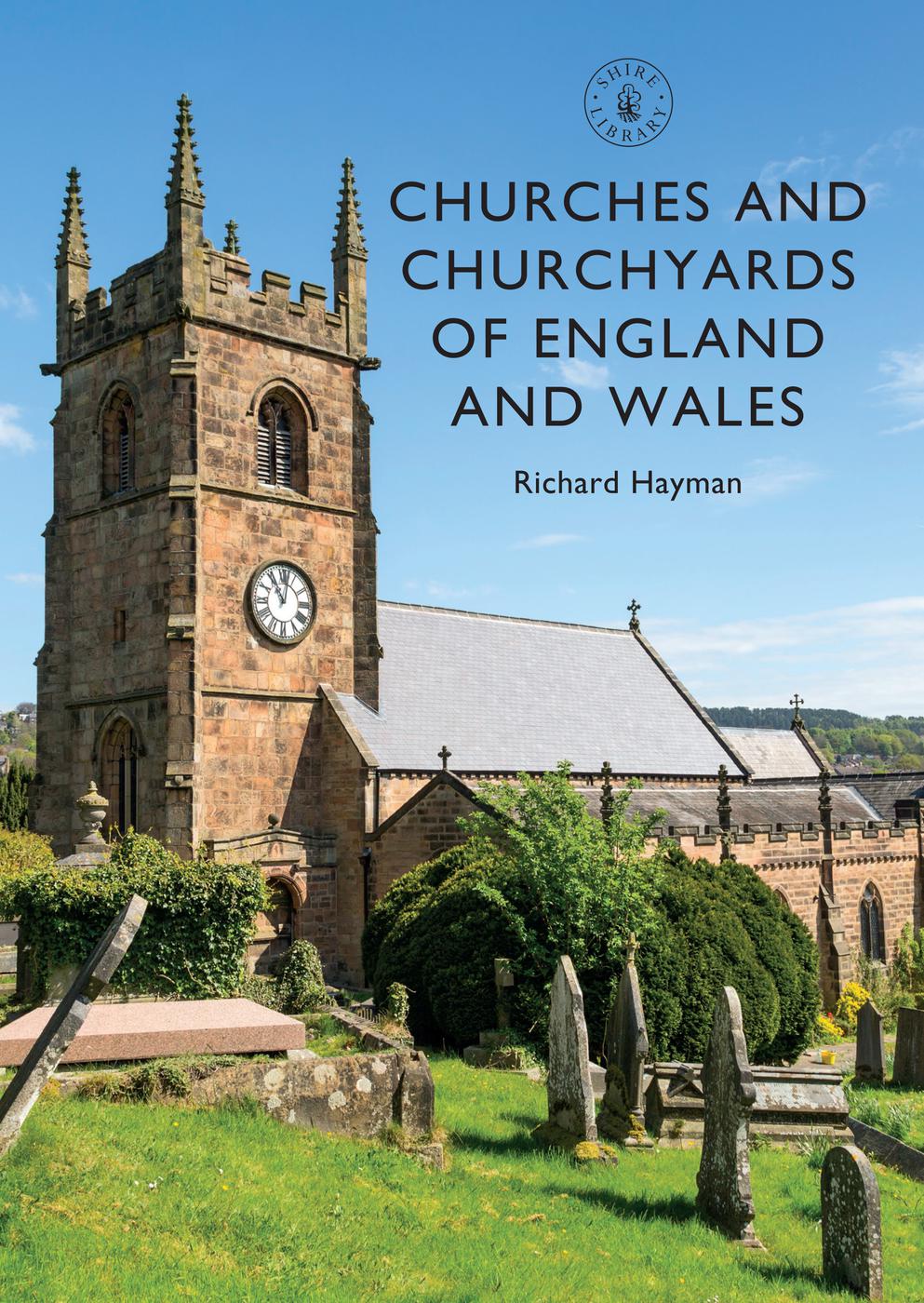

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

THE BROAD SWEEP OF HISTORY

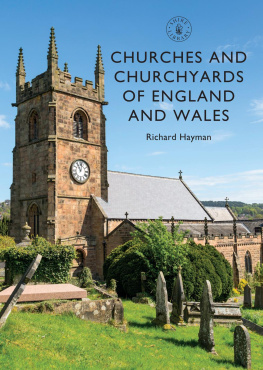

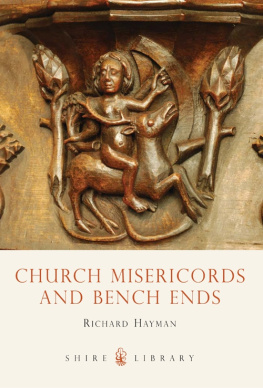

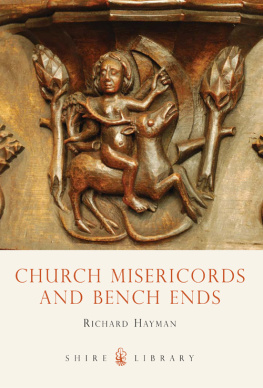

S TOKE-SUB-HAMDON CHURCH stands at the foot of Ham Hill in south Somerset, in a churchyard entered by a seventeenth-century gateway and surrounded by monuments and headstones of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Built mainly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and restored in 1862, the church has an untidy cruciform plan with the thirteenth-century tower placed on the north side instead of over the crossing. Although not especially remarkable by Somerset standards, the building is full of incident, with windows of different styles and dates, carvings around the outside of the building, a richly decorated Norman chancel arch, sixteenth-century funeral monument and a seventeenth-century altar table. Above the doorway in the vaulted porch is a carving made in the mid-twelfth century of Sagittarius shooting an arrow at Leo, the two of them separated by the Tree of Life, on which bi rds peck fruit.

Stoke-sub-Hamdon church is unique, in the same way that every parish church is unique. It is also an exemplar of what makes parish churches worth visiting and re-visiting. We are used to looking at history one period at a time, but a church rarely allows us to do this. In over 1,500 years of Christian history, churches have undergone radical changes for doctrinal reasons, styles have gone in and out of fashion, old materials have needed to be replaced, individuals have sought to impose themselves on the building for posterity, and the surroundings of the church have changed. Historical periods are more often than not jumbled up in the church and churchyard. For all these reasons a church is not fixed in time and to appreciate a church is to appreciate the sweep of history in a single view. Stoke-sub-Hamdon is just one of several thousand churches that allow us to do that.

Above the doorway at Stoke-sub-Hamdon this twelfth-century tympanum shows Sagittarius and Leo, the Tree of Life, and Agnus Dei (or Lamb of God), a curious and not wholly comprehensible collection.

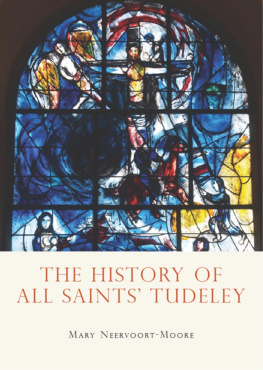

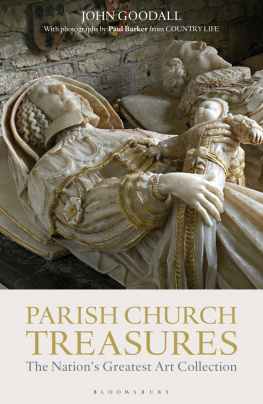

A parish church is much more than the embodiment of our religious history. Churches represent most of our oldest buildings, and the oldest of our buildings still in use. Despite this, the parish church remains the foremost work of architecture in most English and Welsh villages and towns. The manor next to the church, the imposing funeral monuments inside the church, and the seating arrangement, which can reveal evidence about the separation of social classes and of men and women, tell us much about our social history, especially of the past 500 years. The churchyard and its monuments add yet another layer to the social history of the village. No institution has been a greater patron of the arts than the Church. It continues to commission works of art in glass and wood and stone but it is a tradition that goes back to Saxon times. It is increasingly recognised now that churches are the museum and art gallery of the nation.

Most parish churches have funeral monuments that are an important part of the nations social history. At Stamford St Martin (Lincolnshire) is the monument to John Cecil, fifth Earl of Exeter, erected in 1704.

The Anglo-Saxon figures in the church at Breedon-on-the-Hill (Leicestershire) are among the oldest works of sculpture to survive outside of a museum.

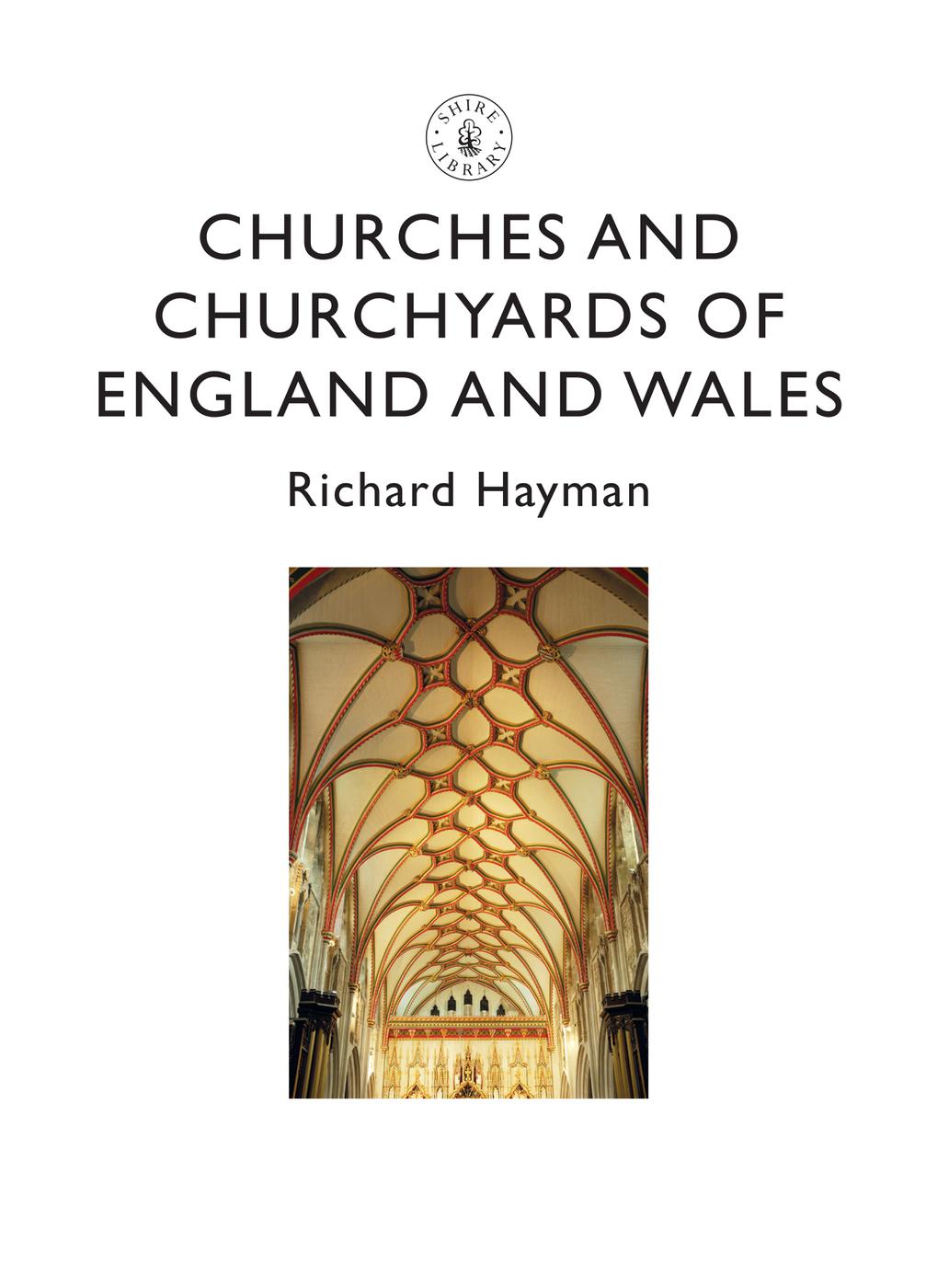

The aim of this book is to explain why English and Welsh churches and churchyards look as they do and how their appearance has changed over time. Perhaps the greatest changes have occurred in the churchyard, which are now sober places for quiet reflection but in the past were host to outdoor gatherings of the parish or the town, for leisure, business and even sport. The church is the setting for Christian worship, but as forms of worship changed so did the buildings and their furnishings. In the medieval period, to open the door of the church was to encounter a representation of heaven on earth, or at least as close an approximation to it as resources would allow. It is why efforts were made to glorify the church in both architecture and decoration. What is often forgotten is that these churches were built, furnished and maintained by their own congregations, but the way in which popular religion directed itself to building and beautifying churches ended at the Reformation in the mid-sixteenth century. After the Reformation churches were built and furnished in a more utilitarian manner, reflecting the different emphasis of Christianity on the Word rather than the image. The Victorians revived much of the style and symbolism of the medieval church building, although not the communal effort in paying for it s construction.

Medieval stone coffins can be found in numerous churchyards in the north of England, like this example at Darley Dale (Derbyshire). Many of them were discovered during church restoration work.

The grain of the nations history runs through our parish churches. It is also one of the most accessible forms of heritage. There is a church in every town and village, which has as much to offer the informed observer on the inside as it has on the outside. Unlike most forms of heritage, churches remain in use and are open to the public or at least most of them are, even if it means looking on the noticeboard for the keyholder. Churches are the perfect way for independent-minded people with an ounce of curiosity to ex plore the past.

Kington (Worcestershire) has two modern windows made in the 1980s by John Petts of Abergavenny.

Llangurig (Powys) was the site of an important clas in the upper Wye valley. The village came later.

HISTORY OF THE PARISH CHURCH

T HE PARISH IS the basic unit of church administration, serving the pastoral needs of local communities, under the umbrella of the diocese ruled by a bishop and, ultimately, archdioceses, of which there were only two in medieval England and Wales. This church hierarchy is more than a thousand years old. In England it emerged in the late Saxon period, although in some parts of the country, notably the politically unstable Marches of Wales, the parish system was still evolving in the twelfth century. However, the parish system as we know it today was not designed; it developed slowly, often illogically, and most of our medieval parish churches did not begin life serving a pa rish community.

English and Welsh churches with the earliest origins usually began as monasteries, minsters or individual chapels for hermits or high-ranking priests. This was equally true in Wales, where an early monastic church was known as a clas , some of which are now within the borders of England. A lot of what we know about early monasteries is derived from the writings of church historians because many individual monasteries and chapels were founded by notable saints. Foundation myths were important in medieval Christianity, not least to remind monks and nuns of the high standards set by their forebears. Endowment of a monastery was one way in which lay people of rank could express piety and many of them were founded in the seventh and eighth centuries. In this period, however, not all monastic foundations lived up to the image of disciplined isolation, such as on Holy Island (Northumberland). Bede, in a letter written in 734, sharply criticised many of the monks there, and was scornful of so-called monasteries that were lax institutions founded by reeves or thegns who simply declared themselves abbots, but had an ulterior motive of acquiring land for themselves. Subsequently there was a decline of monastic foundations, due in part to the threat of Viking incursions, and early monasteries are more likely to have become parish churches than to have thrived until the time of the Reformation. Monasticism was revived under the influence of Dunstan of Glastonbury in the tenth century, but in the more recognisably medieval form of the international orders. In this period local lords were less inclined to found religious communities, so built private chapels for their o wn use instead.