Bloomsbury Continuum

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square

London

WC1B 3DP

UK | 1385 Broadway

New York

NY 10018

USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2015

John Goodall, 2015

Photographs Paul Barker, 2015

John Goodall has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4729-1763-8

ePDF: 978-1-4729-1765-2

ePub: 978-1-4729-1764-5

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 Inheritance, Before the year AD 1000

CHAPTER 2 Genesis, 1000-1199

CHAPTER 3 The Church Triumphant, 1200-1399

CHAPTER 4 The Late Medieval Parish, 1400-1535

CHAPTER 5 The Tudor Reformation, 1536-1603

CHAPTER 6 Protestant England, 1603-1699

CHAPTER 7 The Anglican Church, 1700-1799

CHAPTER 8 Revival and renewal, 1800-1899

CHAPTER 9 The 20th Century and the Millennium, 1900 to the Present

Introduction

Our parish churches constitute a living patrimony without precise European parallel, their architecture and fittings the product of sustained patronage that, in some cases, demonstrably extends back well over a millennium. The cumulative product of that investment is a physical palimpsest of almost unbelievable complexity and interest. Their cultural riches are astonishing not only for their quality and quantity but for their diversity and interest as well. Fine art and architecture here combine unpredictably with the functional, the curious and the nave, as a complementary backdrop to the life of the local church.

In this sense these buildings effectively form an unsung national museum that, unlike all its institutional rivals, presents its contents in an everyday setting without curators or formal displays. The objects themselves also preserve an unrivalled authenticity of place. There are many exceptions and complications to the rule, but the contents of parish churches often remain in the building for which they were first created. That continuity links us directly with those who created them, sometimes across enormous periods of time. Properly interpreted, therefore, parish churches tell from thousands of local perspectives the history of the nation, its people and their changing religious observance.

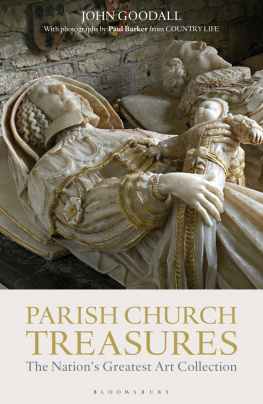

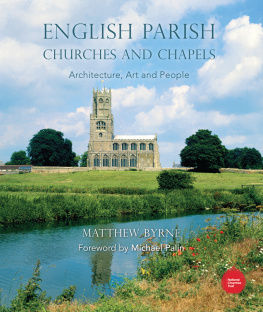

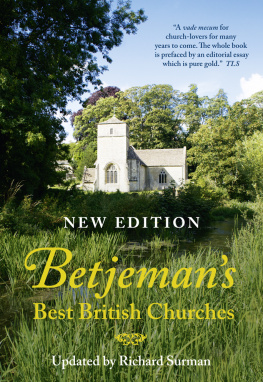

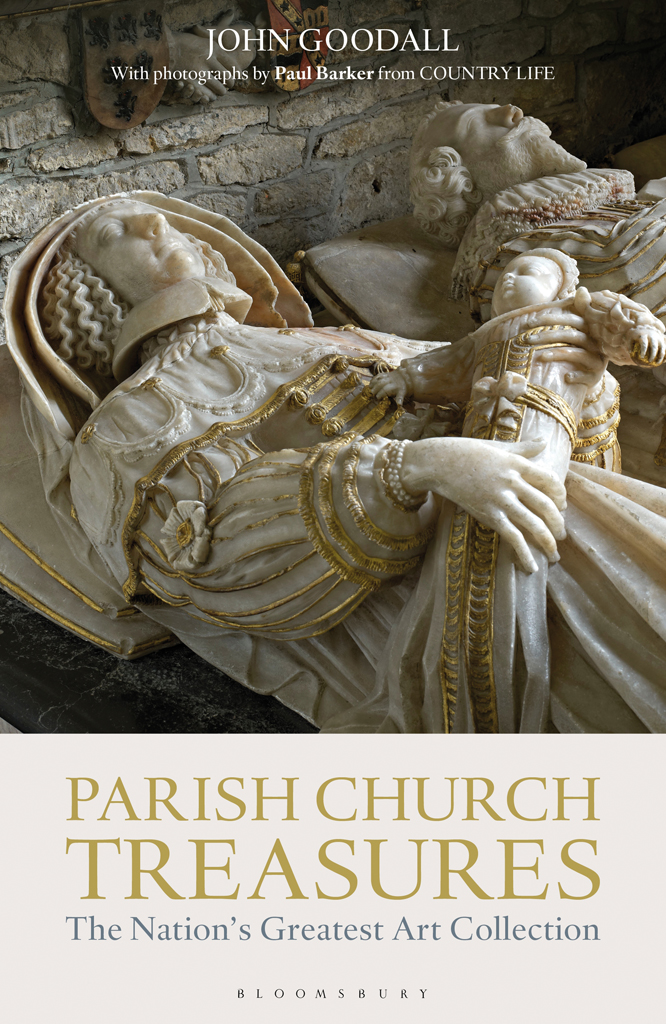

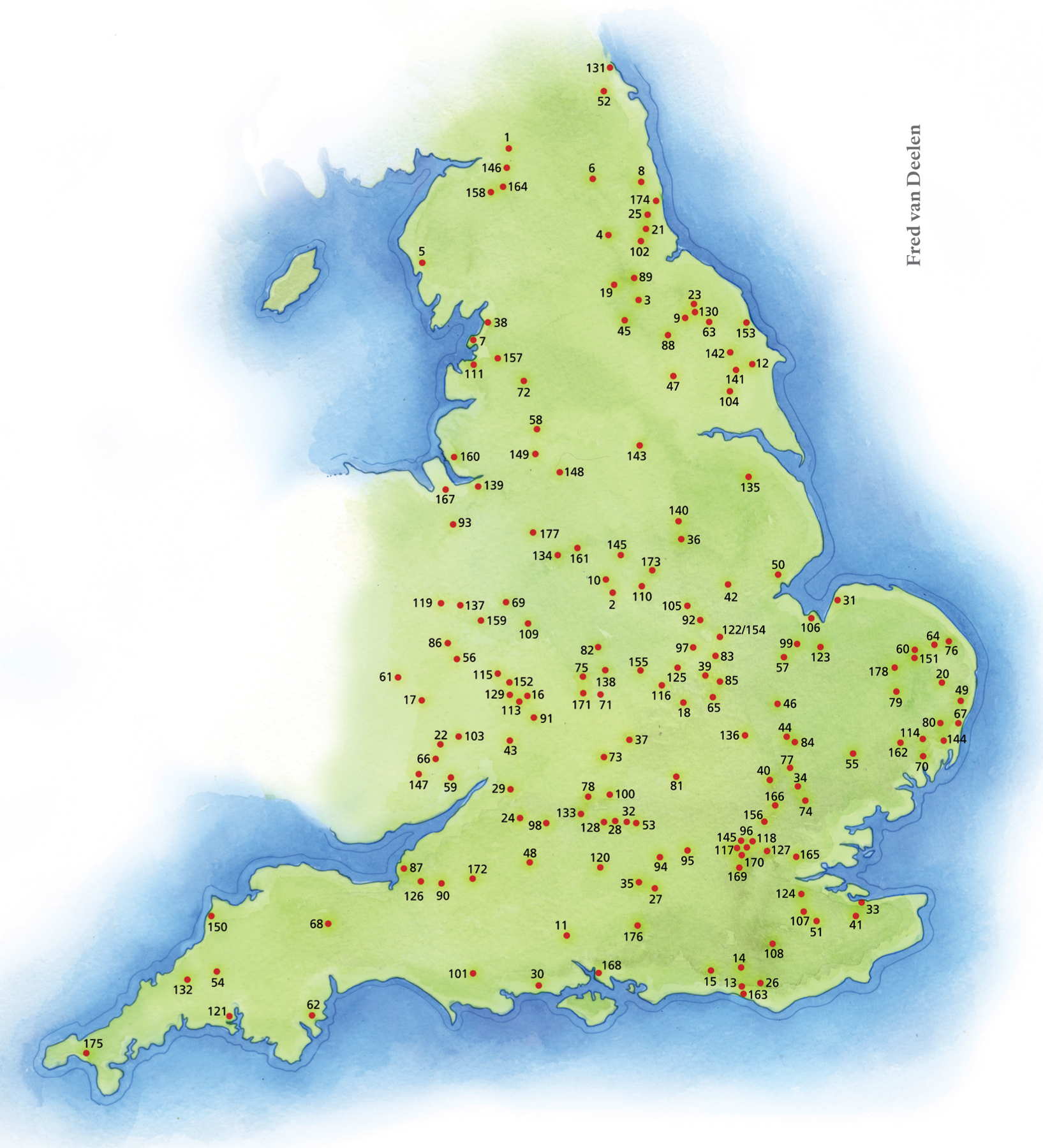

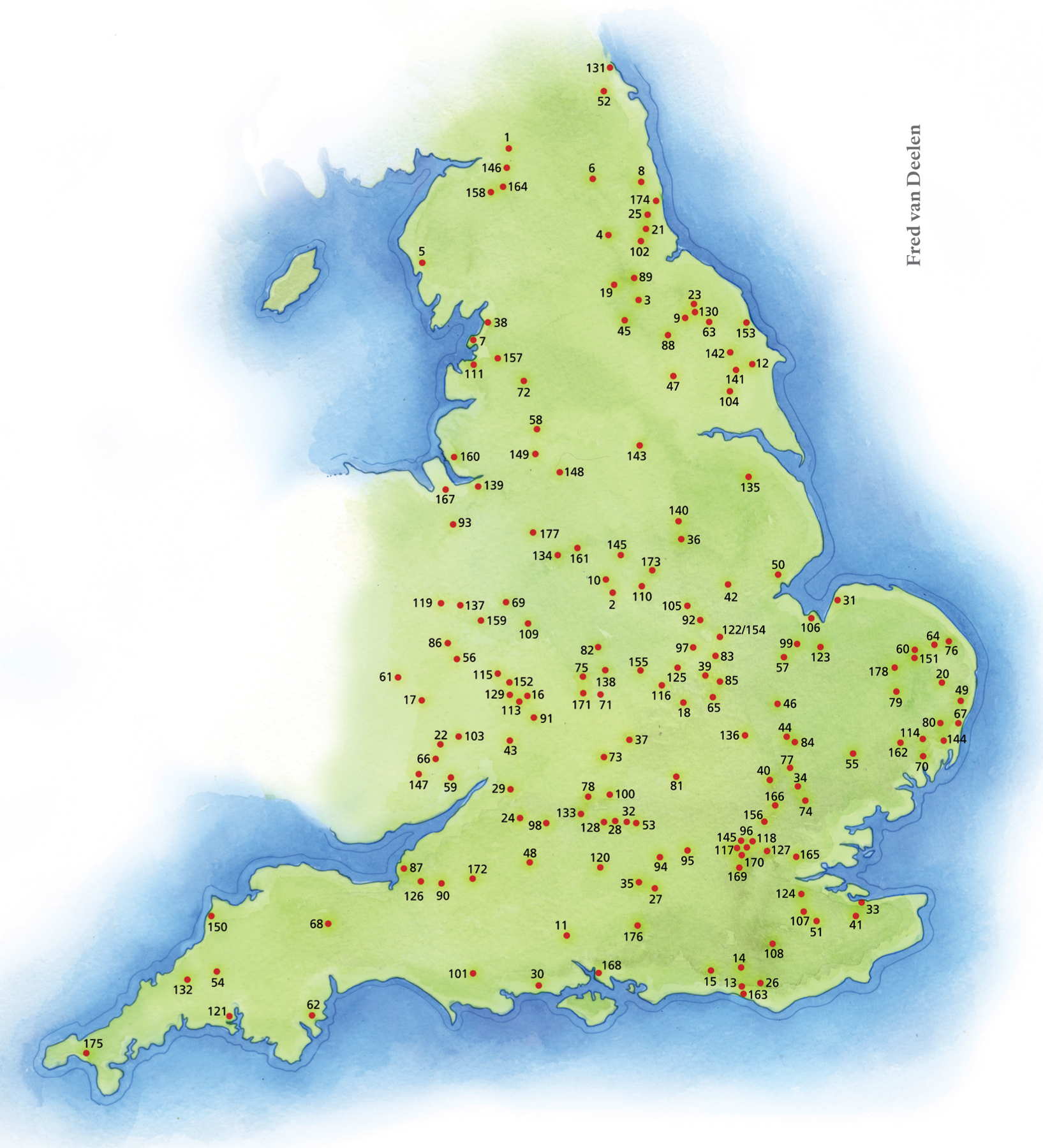

This book is an attempt to celebrate these riches in a way that is at once accessible, delightful and thought-provoking. It has developed from the seed of a weekly series entitled Parish Church Treasures published in Country Life since the autumn of 2012. Each week this presents a short, focused article on a single object in a different parish church. Brought together within the pages of this book are about 170 treasures, each individually photographed in location by Paul Barker and assembled within a series of nine chapters. These are prefaced with short introductory essays that tell within an overarching chronological structure the story of the parish church from the remote past to the present day.

The selection of treasures that form the backbone of this book deliberately looks beyond objects of merely marketable value. In part this is because valuables, such as church plate, are necessarily locked away, and I wanted to celebrate things that can be seen on a day-to-day basis. It would be rash to make promises for the future, but most parish churches are accessible through no more than a preparatory telephone call. Some may lament the fact that the doors of some churches are often closed but this accessibility remains extraordinary. In any case, sometimes it is not even necessary to go through the door to enjoy something unexpected and truly exceptional.

But this focus was not dictated merely by practicalities. People are normally well aware of things that are worth large amounts of money and accord them respect (recent history has also shown that an awareness of value can encourage parishes to sell the objects that make them special). By contrast, the invaluable or at least the inalienable are regularly overlooked, almost regardless of their beauty and importance. The local communities that proudly maintain churches are usually only concerned incidentally with their history. They can also find it hard to grasp the full significance of objects that have become familiar.

Why in particular should this matter now? The answer is because parish churches are currently undergoing a massive and collective change as congregations seek to modernize their interiors. As a background to this, moreover, communities are struggling to maintain buildings that, because of their quality, are costly to repair. In scale and significance these transformations will have a physical impact that easily matches that of the great nineteenth-century restorations that created many of the interiors we see today.

To posterity, the present reordering boom will merely be one more episode in the long and eventful history of these buildings. Yet, as with all moments of change, it entails real dangers to the fabric of churches and their contents. Outstanding among these dangers is the possibility that things will be neglected or even destroyed because a parish lulled by familiarity into indifference or intoxicated by an enthusiasm for change or simply because of a preoccupation with other, more pressing priorities grossly undervalues them. What better moment, therefore, to highlight the significance and diversity of such cultural riches?

No less important is the need to champion at this critical moment the unique character of these buildings as places that transcend familiar concepts of ownership and use. For as centres of religious life, parish churches are more than just historic monuments; as village or public buildings they are more than simply the possession of their congregations; as works of architecture and receptacles for art they are more than sheds for worship; and in some cases as buildings or at least sites of breathtaking antiquity, no one generation has unquestioned rights to do as it pleases with them (though each generation must necessarily take complete responsibility for them and can expect no help from the past or posterity in the burden it carries).