GOING TO CHURCH

IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND

Copyright 2021 Nicholas Orme

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed and bound in China

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021935426

ISBN 978-0-300-26261-2

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Grace

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

The author and publishers are grateful for the permission to reproduce granted by the copyright holders listed below.

FOREWORD

From at least about AD 597, when St Augustine started his mission to the English at Canterbury, Christianity reached the people of England through churches. The earliest were those known as minsters, staffed by groups of clergy. These were joined and to a large extent superseded from the tenth century by much greater numbers of local parish churches, run by single clergy. By about the year 1200 England possessed some 9,500 churches of both kinds, forming a network that covered the whole of the country. Until the Toleration Act of 1689 they were places which every adult was expected to attend for baptism, marriage, and burial, to visit for worship on Sundays and festivals, and to support by helping to maintain the buildings and their furnishings. Many thousands of medieval parish churches still survive in their original or altered forms, as do most of their territories or parishes, albeit often with modified boundaries. The following book sets out to tell their story and that of their clergy and congregations from Augustines arrival to the final establishment of a Reformed Church of England under Elizabeth I in 1559.

The presence of churches all over England, their relationship with its people, and their functions as buildings and places of worship, music, and art make them relevant to a wide range of historical studies. They were important in the institutional history of the Church, as the means by which it ministered to lay people and sought to regulate them. They formed part of the power of the crown and the privileged orders of society, and were centres of the social and economic life of local communities. From the 1530s they were involved in the political and religious changes that accompanied the Reformation. They are also helpful in understanding other disciplines than history. In the realm of medieval literature, they, their staff, and their worshippers appear in Langlands Piers Plowman and Chaucers Canterbury Tales, as well as the works of Robert Mannyng, John Mirk, Dives and Pauper, Margery Kempe, and Alexander Barclay among others. They provide crucial evidence for the history of liturgy (how worship was organised), music, architecture, and the decorative arts.

The breadth of this relevance has made it hard for scholars to keep all the aspects of their history within a single survey. The historians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who first studied the functioning of medieval parish churches did indeed try to do justice to several of these aspects at the same time. Daniel Rock, J. C. Cox, Henry Littlehales, and other such figures up to about the 1920s sought to produce composite accounts of churches from documents, architecture, furnishings, literature, and liturgical texts.

The present volume seeks to address more of these aspects so as to give a broader and deeper account of parish church history. It follows mainstream history in dealing with institutions and social groups, but also concerns itself with liturgy and with buildings in terms of their interior spaces, furnishings, and usage. It draws on literary sources where this is possible, with the additional hope of elucidating them. It does not attempt to argue a particular thesis about medieval parish churches. This is not feasible given a coverage of hundreds of years, thousands of churches, and millions of people. Churches varied in structure, leadership, and resources, and their story involves a complex mixture of opposites: devoutness and indifference, good and bad behaviour, equality and privilege, communality and coterie. Rather this book sets out to reconstruct how churches worked as religious centres: what happened inside them. Its information is drawn widely from across England to make it a national study, not a regional one. Its object is to help students of all disciplines, as well as general readers, to appreciate the major elements of parish church history within the covers of a single book. The first chapter traces the emergence of an organised Church in Roman Britain and Anglo-Saxon England, and shows how parish churches, parishes, and congregations came into existence up to the Norman Conquest. Six further chapters survey the main features of their activities through the centuries from then until the 1520s, while an eighth considers the impact of the Reformation.

The focus of the book is on people in church. It examines who organised the worship and religious affairs of a parish: the officiating clergy and the laity who assisted them. It describes the buildings to which people went, and the significance of their shapes and furnishings. It asks how far a parish church helped to mould its worshippers into a community, and how far other factors caused the community to divide into smaller groups. It tries to explore the extent to which parishioners went to church or did not go, what they experienced when they came, and how they behaved in church. The history of Church services the topic of medieval liturgy is a particularly difficult subject, and a principal aim of the work is to provide an easy way in to understanding it. How did a church, its leaders, and its people worship each day, each week, and each year? How did they provide for and try to control the great events of life: birth, coming of age, marriage, sickness, and death? What was given in terms of spiritual ministry through the mass, through teaching, and through the cults of Christ and the saints? Finally how far were the structures and behaviour characteristic of the Middle Ages altered during the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century? Accounts of the Reformation usually emphasise change, but the study of Church organisation and worship during that process reveals many continuities.

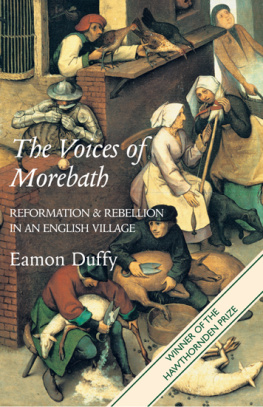

I am grateful for the kindness of many people who have given me advice and information. Paul Barnwell, Helen Gittos, David Lepine, Nigel Morgan, Nigel Saul, and two assessors kindly read parts or all of the text to its advantage. I am also indebted to John Allan, Caroline Barron, John Blair, Roger Bowers, Clive Burgess, Eamon Duffy, Brian and Moira Gittos, Sarah Hamilton, John Harper, Martin Heale, Diarmaid MacCulloch, Joanna Mattingly, Valerie Maxfield, Nigel Ramsay, Gervase Rosser, Robert Swanson, Sheila Sweetinburgh, Magnus Williamson, Peter Wiseman, and Tyanna Yonkers for their writings or for answering particular questions. Many thanks are due to the staff of the Bodleian and Exeter University Libraries, as well as to John Allan, Alison Barker, David Cook, Michael Swift, and Diane Walker, who kindly provided some of the illustrations. My last deep obligation is to Lucy Buchan, Percie Edgeler and Eve Leckey for their tireless work on the illustrations, design, and text of the book.

Next page