THE VOICES OF MOREBATH

Copyright 2001 Eamon Duffy

First published in paperback 2003

3 5272921028262422

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Typeset by Northern Phototypesetting Co. Ltd, Bolton Printed in Italy

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN- P UBLICATION D ATA

Duffy, Eamon.

The voices of Morebath: reformation and rebellion in an English village / Eamon Duffy.

p. cm.

Includes index.

1. ReformationEnglandMorebath. 2. Morebath (England)Church history16th century. 3. Trychay, Christopher, ca. 14901574. I. Title.

BR 377.5.M67 D84 2001

274.23'52-DC21

2222222222222222222 2001001477

ISBN 0 300 09185 0 (hardback)

978-0-300-09825-9 (paperback)

FRONTISPIECE: The Alchemist, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1558? detail. Staatliche Museen, Berlin

TITLEPAGE: Sir Christopher Trychay's signature,

from a list of regulations for the maintenance of the church hedge

[Binney 38 / Ms 181], see pp. 501.

for

Jonathan, Hester, Pippa

at their goyng forthe

Contents

Acknowledgements

While writing this book I have accumulated obligations to a host of friends and colleagues who have offered insight, advice, information, expertise, hospitality or merely an indulgent ear Dr Ian Arthurson, Mr T. Cooper, Dr David Crankshaw, Professor Pat Collinson, Dr Beat Kumin, Dr Joanna Mattingly, Professor John Morrill and and Ms Helen Weinstein. I owe special debts of gratitude to Sir David and Lady Calcutt for hospitality on Exmoor and for the sight of an archdeacon chasing someone else's hat, to Jim and Mabel Vellacott of Bampton and Morebath Jim and Mabel at Wode who walked and talked me round the farms of Morebath, to Richard and Caryl Rothwell of Little Timewell for access to the estate map of Morebath Manor, to Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch for making me think twice, to Dr Neil Jones for unrivalled expertise in Tudor law, to Professor Nicholas Boyle, who read every word and commented constructively on almost all of them, and to Dr C. S. Knighton who also read the typescript. I thank them all. Professor Nicholas Orme has been from the beginning of this project a generous and supportive friend. A glance at the footnotes will reveal how often I have borrowed from his deep knowledge of the religious history of Devon. In addition he has been a tireless source of hospitality, information and guidance, and a healthily sceptical reader: this would have been a far poorer book without him.

The Bethune-Baker fund of the Cambridge Faculty of Divinity and the Morshead-Salter fund of Magdalene College made research grants. John Nicoll and Sally Salvesen at Yale have again proved themselves peerless publishers and warm friends, and Margot Levy was a thorough and intelligent copy editor. I am grateful to the Rector of Bampton and the Devon County Archivist for permission to reproduce pages from the Morebath account-book, and I am grateful for the efficiency and cooperation of the staffs of the Devon Record Office, the Somerset Record Office, and the West Country Studies library. The final stages of the book were completed as McCarthy Professor at the Gregorian University, Rome, in the gracious setting of the Collegio Irlandese, where I was welcomed with truly Hibernian kindness by Monsignor John Fleming, Rector, and his staff and students.

Finally, I thank my wife Jenny, best support of all, who has borne heroically with marriage to Sir Christopher Trychay.

A note on names and spelling

This is a book about the voice of a sixteenth-century man; I have therefore felt it essential to present to the reader what Sir Christopher Trychay wrote, in the way that he wrote it. I have retained the Tudor spelling in all quotations (this is less difficult to understand than may appear at first glance readers who are daunted should try reading the passages aloud, and will be surprised how often the sense clarifies itself. I offer such brave readers three clues Sir Christopher uses y to speak about himself, I'; he uses a separate word, ys', to indicate a genitive, where we now use an apostrophe s John Wode ys brother' for John Wode's brother'; and he frequently uses double s or double t where we use sh or tch parysse for parish, fett for fetched'). But for comfort's sake, and since it is my hope that readers other than professional historians may find the story of sixteenth-century Morebath of interest, all extended quotations are followed by a modernised version, printed in italics. In shorter quotations, I have translated all hard words in square brackets, and I have translated all the Latin.

The 1904 edition of the Morebath accounts by J. Erskine Binney, while not quite complete and sometimes inconsistent in capitalisation and division of the text, is basically reliable. I have worked from the manuscript in the Devon Record Office in Exeter, but since the printed edition is the version of the accounts available to most readers of this book, I have chosen to quote from Binney's text, except in the few places (clearly indicated) where his transcription positively misleads. For those who wish to pursue them, page references to the current (but chaotic) binding of the manuscript are given immediately after the page numbers in Binney's edition.

For clarity's sake, I have provided arabic equivalents for all roman numbers, even in the Tudor text, and in translating money sums have used the modern symbols for pounds, shillings and pence. I have silently expanded all conventional abbreviations, and have very occasionally and very conservatively added punctuation to clarify specially complex passages. Following a misleading Victorian convention, Binney transcribed the obsolete letter thorn as y': I have substituted the more accurate th'. The obsolete letter yog', which he transcribed as z', presented greater problems. There is no stable modern equivalent for Sir Christopher's somewhat erratic use of this symbol, and it never assists the sense. I have thought it simplest to omit it.

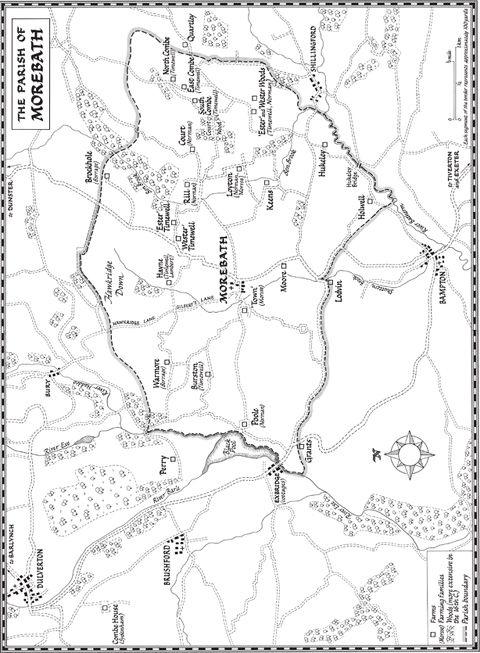

Spelling of family and place names vary greatly in the manuscript: outside direct quotation, I have opted for the spelling in the modern ordnance survey maps of Morebath, and have also used the generally current versions of family names such as Hurley (instead of Hurly'): the only exception is Sir Christopher's own surname, which I have spelt throughout as he did.

I have taken the opportunity of a fourth printing to include details of a rather startling incident on p. 164.

Preface

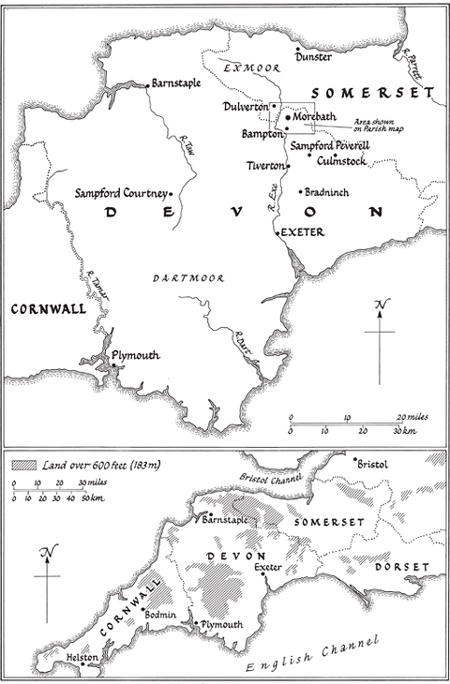

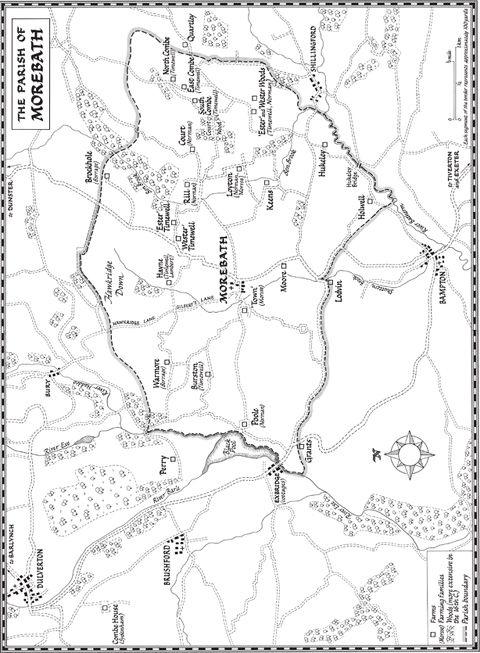

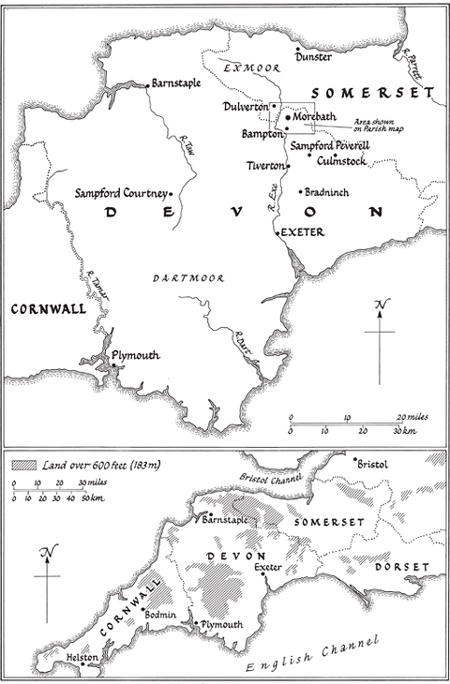

This is a book about a sixteenth-century country priest, and the extraordinary records he kept. It deals with ordinary people in an unimportant place, whose claim to fame is that they lived through the most decisive revolution in English history, and had a priest who wrote everything down. Morebath was and is a tiny Devonshire sheep-farming village, which in the sixteenth century was made up of just thirty-three families, working the difficult land on the southern edge of Exmoor. The bulk of its conventional Tudor archives have long since vanished: there are no manorial records, and most of the ancient wills of the region went up in smoke during the bombing of Exeter in the Second World War. But for more than fifty years through all the drama of the English Reformation, Morebath had a single priest, Sir Christopher Trychay (his surname is pronounced Trickey', to rhyme with Dicky, and Catholic priests then were called Sir as now they are called Father'). Sir Christopher was vicar of Morebath from 1520 until his death in 1574. Opinionated, eccentric and talkative, he kept the parish accounts on behalf of the churchwardens. There are more than two hundred surviving sets of churchwardens' accounts from Tudor England, but none of them like Morebath's. Almost everywhere else these accounts are what they sound like bare bones, dry records of income and expenditure. The Morebath accounts contain all that, but they are packed as well with the personality, opinions and prejudices of the most vivid country clergyman of the English sixteenth century, and with the names and doings of his parishioners. Through his eyes, or rather, through his voice, talking, talking, talking for he wrote these accounts to be read aloud to his parishioners we catch a rare and precious glimpse of life and death in an English village. His accounts reveal its complex social life, its strains, tensions and conflicting personalities, its search for internal harmony, its busy pre-Reformation piety, its struggles to meet the growing demands of the Tudor war-effort against Scotland and France.

Next page