THE HISTORY OF ALL SAINTS TUDELEY

Mary Neervoort-Moore

Interior of All Saints Tudeley from south door. (P. Ive)

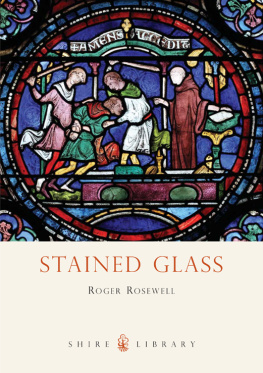

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

The organ and barrel-vault ceiling. (R. Ive)

CONTENTS

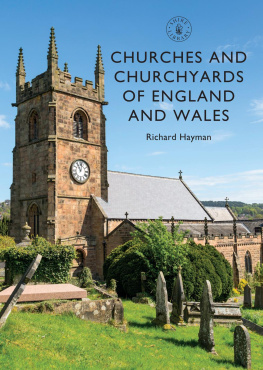

The eighteenth-century tower of All Saints Church.

EARLY CENTURIES TO THE MEDIEVAL PERIOD

J UDGING BY EXTERNAL APPEARANCES anyone could be misled into thinking the history of All Saints Church, Tudeley, began in the eighteenth century as some guidebooks have suggested. Many events and influences have shaped village and Church century by century, and the history of the church and parish are so intertwined they cannot be separated.

Robert Furley, in his History of the Weald of Kent (1871), although scornful of Tudeley as a place of interest acknowledged that it was a place of antiquity this can be largely attributed to the established working of iron ore which had been smelted locally long before the Roman occupation. The date of that early settlement is not known, although there are some who claim that the Phoenicians came up the River Medway in their galleys to trade here for iron. Certainly when the Romans came in AD 43 there was a great increase in the smelting of ironstone; blooms of refined iron were exported to Rome until the end of Roman rule in Britain in AD 410.

Traces of a forge still exist 650 yards west of the church at the bottom of a deep escarpment through which a stream runs which was known as the Devils Gill. The stream still runs, though to local farmers it is now known only as the Gill.

Yet another indication of Tudeleys antiquity comes from the beginning of the seventh century, the early days of Christianity in Britain when Kent was a Saxon kingdom. The Weald of Kent in the early seventh century was a vast and dense oak forest, reaching almost to the sea. At that time there were only four churches in the whole of the Weald Hadlow, Tudeley, Benenden and Palster.

That there was already a settlement with a forge established in Tudeley may explain why it was one of the four places in which an early Saxon church was sited, although nothing remains of that earlier building.

View across the Medway valley from the churchyard of All Saints, looking north-east.

It was during the late Saxon period that the first church was built on the present site of All Saints. The building no longer stands, but the sandstone footings of the nave and tower of the present church are the foundations upon which the Saxon church was built.

At the end of the Saxon period, the Domesday Book (1086) recorded that Eddeva held it of the king and that it is and was always worth 15s TRE. TRE refers to the last year of Edward the Confessor (the last Saxon king recognised by the Normans) and Eddeva is probably Edith of Wessex (the wife of Edward the Confessor and the sister of the future king Harold II), who since 1018 had also held the neighbouring manor of Hadlow, although others have argued that she was Eddeva the Fair, otherwise known as Edith Swan-neck (the common-law wife of Harold II).

The last of the Saxon kings, Harold II, was killed at the battle of Hastings in AD 1066. The new king, William Duke of Normandy, better known as William the Conqueror, proceeded to portion out the land of his newly conquered realm to his family, friends and followers. He rewarded his halfbrother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux with vast possessions of land, including Tudeley, and also created him Earl of Kent.

The entry in the Domesday Book refers to Tudeley Tivedele being held by Richard de Tonbridge of Odo. It reads as follows:

In Wechylstone Hundred Richard of Tonbridge holds TIVEDELE of the bishop. It is assessed at 1 yoke. There is land for 1 plough and there is [1 plough] in demesne and a church and woodland for 2 pigs.

St Thomas Becket Church, Capel.

The wall painting of the Last Supper in St Thomas Becket church, Capel.

In 1082 Odo was disgraced and imprisoned with the result that in 1084 his lands and all that stood on them including Tudeley were seized by the king.

While the church does not at first glance suggest great antiquity, late medieval masonry still exists in the west tower, the aisle, nave and chancel. According to Textus Roffensis (dated 1123) a chrism fee (a fee payable by the parish to the cathedral in the week before Easter for the consecration of the oil used with baptism and for other purposes) of 9 denarii was paid to the See of Rochester.

Records show there to have been fifty-one incumbents from John, appointed in 1252, until 2014 but virtually nothing remains to record the incumbent previous to the earlier date.

Unlike the many churches throughout the land that were richly endowed, there is little remaining to suggest that Tudeley church and parish enjoyed the benefits of wealthy patronage. Over the centuries the church passed through the hands of many patrons, ending up in 1239 in the hands of the Priory of Tonbridge. It suffered a number of vicissitudes as well as undergoing many periods of demolition, rebuilding and restoration. The living was sequestered in March 1331 when the Archdeacon of Rochester issued a mandate to the Dean of Malling to sequester the Living for the church being allowed to fall into disrepair (an ever-recurring problem).

Around a mile from Tudeley, on a little hill, Thomas Becket is said to have preached beneath a yew tree that still exists. The Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem built a chapel soon after his murder in 1170 next to the yew tree. It remained as a chapel of the order until 1447 and gave its name, Capele, now Capel, to the locality.

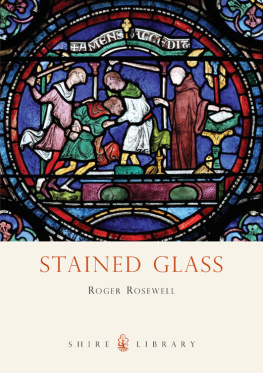

In 1927 a series of thirteenth-century wall paintings were uncovered at Capel by the late Professor E. W. Tristram. Painted between 1230 and 1250 the paintings cover the greater part of the north wall of the nave. The Norman window separates pictures depicting Christs entry into Jerusalem and the Last Supper. In the splays of a single-light window are pictures depicting Cains slaying of Abel.

Ranging from 1329 to 1361, the Tudeley forge accounts, the only Wealden forge accounts extant for that period, show the effect of the Black Death upon the price of iron, which doubled owing to the shortage of labourers. The plague had a devastating effect upon the village, seriously reducing the level of the population.