CONTENTS

STAINED GLASS LOST AND REDISCOVERED: 1530s1815

S tained glass windows are an inspiring, beautiful and rewarding form of art. Their kaleidoscopic colours form vibrant designs which sparkle in the sun and embellish the interior with a bewitching light, displaying the skills of leading artists and craftsmen from across the centuries. These designers had to make them both a functional part of the building that would complement the architecture, while at the same time creating images that would inspire an illiterate congregation to follow a righteous path. Stained glass windows therefore display not only the changing styles of art over the past millennium, but also unlock a treasure trove of history by revealing much about the men and women who designed and commissioned them.

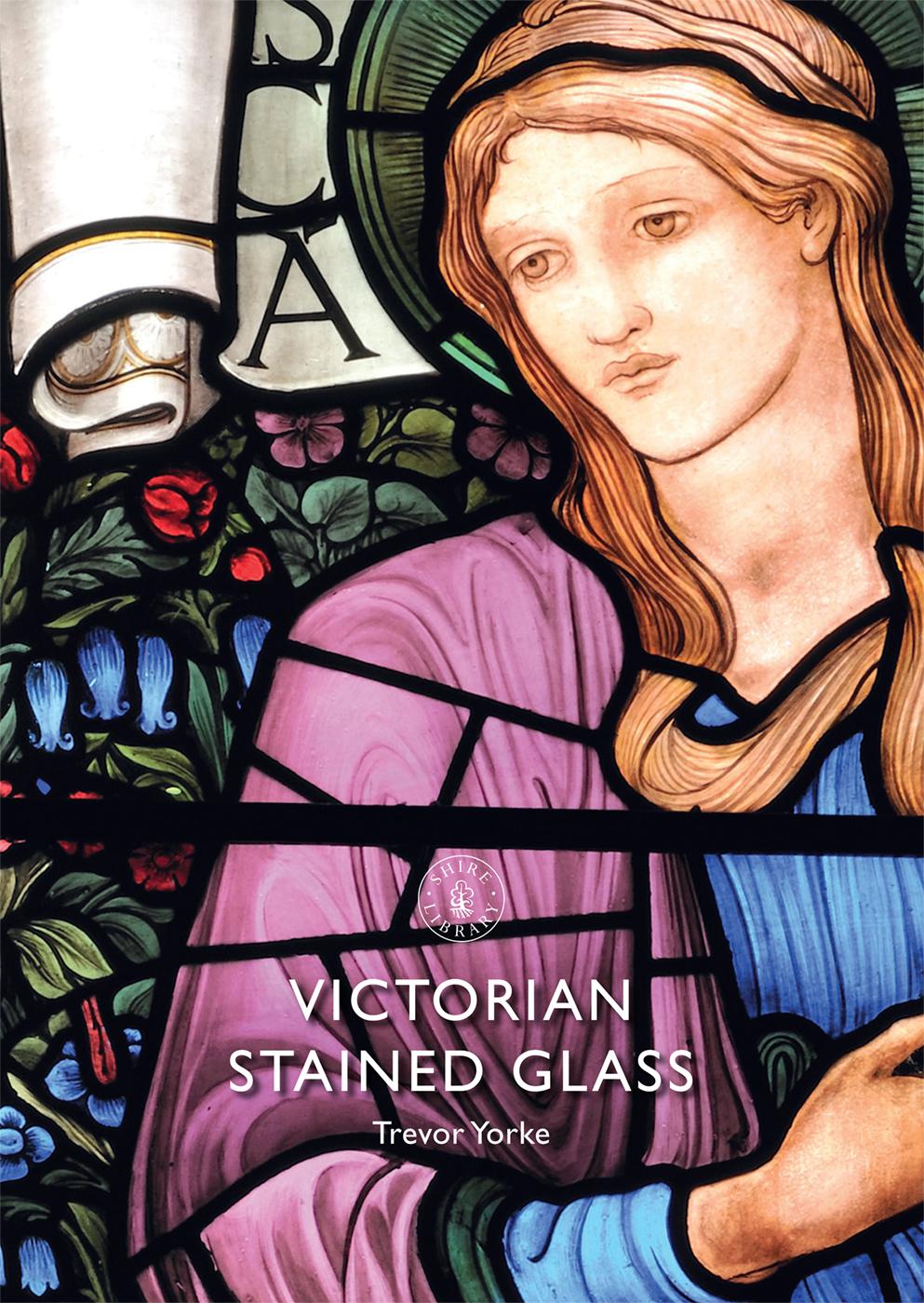

Despite their aesthetic beauty, stained glass windows have a history scaling from periods of high creativity to those of reckless destruction. The message so artistically presented to one generation was viewed as blasphemous by another, while changes in architectural style and technological developments made once-fashionable colourful mosaics seem suddenly out of place. As a result, stained glass windows from the medieval period are rare and often fragmented, but are treasured for their artistic and historic value. The majority found today in cathedrals, churches or private houses date from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when the art form was revived. Victorian artists and designers not only created myriad colourful designs, but also had to rediscover the ways in which the windows were originally constructed. In order to appreciate the task that faced them, it is first useful to understand how stained glass was made, why it fell from favour and what the changes were that inspired its revival.

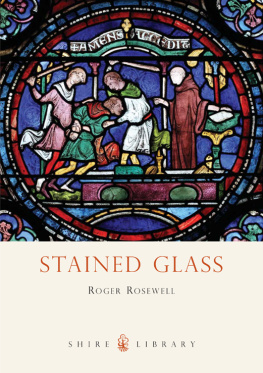

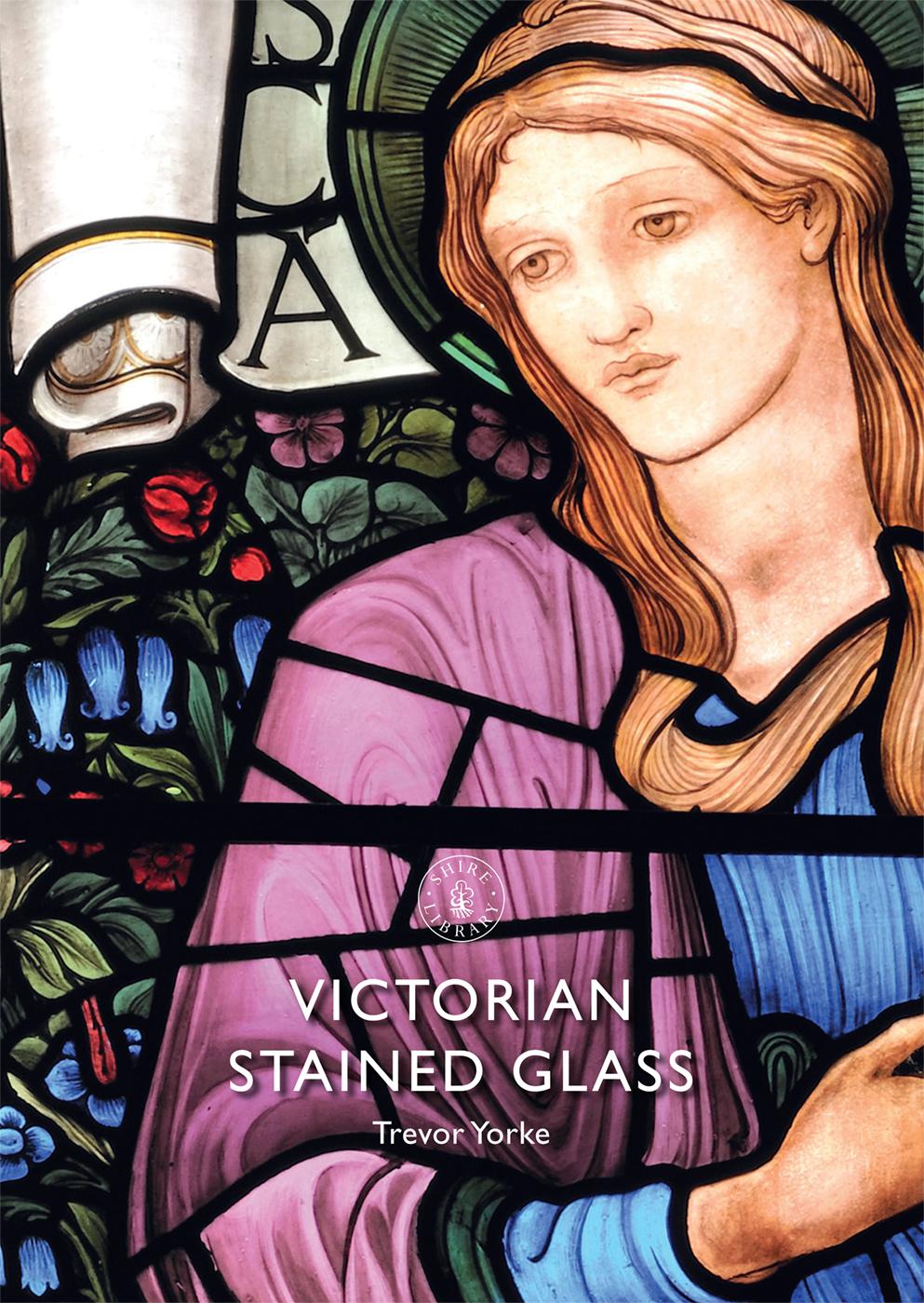

The Victorians meticulously studied medieval stained glass in order to accurately recreate them and then later inspire new forms and styles, as in this beautifully detailed example from Holy Trinity Church, Blatherwycke, Northamptonshire.

Traditional hand-blown or antique glass has been produced in Britain since the Roman period. It was made from silicon dioxide, usually in the form of sand. As this melts at around 1500 degrees Celsius, a flux was required, for instance soda ash, so this would happen at a much lower temperature, which was achievable in ancient kilns. The molten glass produced is soluble in water, rendering it useless as a window material so a stabiliser, for instance limestone, was added to counter this. In order to form sheets of glass suitable for glazing, a number of methods were developed. Muff or cylinder glass was made by fixing a lump of molten glass to the end of a pipe, which was then blown and swung until it formed an elongated balloon shape. It was then removed from the pipe, had the ends cut off, and the remaining cylinder was sliced along its length and flattened out to make a single sheet. Crown glass was formed by blowing and rolling the tube with the molten glass at one end to form a bubble. An iron rod was then inserted at the other side and the blow pipe detached, with the glass then spun to form a flat disc which was cut up to form the small panes known as quarries. As the molten glass cooled, the outer surface solidified before the core, which could cause it to crack, so the temperature was lowered gently over a number of days in a process called annealing.

Coloured glass was created by adding metallic oxides before the initial firing in the kiln. Iron oxide could be used for yellow, cobalt for blue, copper for green and gold for reds. These were added to the silica, soda and lime mix and fired in a clay pot within the kiln; hence, this is known as pot metal glass. A problem with some colours, especially ruby red, was that the glass was too opaque. A method called flashing was therefore devised, in which a molten bubble of clear glass was dipped in red glass to leave a thin coating that was more translucent. Glaziers soon realised that by using acid to etch away the flashed coat they could create a new effect called abrading. The vast majority of the windows we see today comprise coloured rather than stained glass, the latter being a term that only became popular in the Victorian period. Stained glass actually refers to a method introduced in the early fourteenth century, when it was discovered that by applying silver nitrate to clear glass and then firing it again in a kiln it created a yellow stain. This was useful for British glaziers, as only clear glass was produced in Britain; coloured glass had to be imported from France or the Rhineland.

The final stage was to add the lines and shading to the pieces of glass with a dark brown or black paint made from iron or copper oxide and ground glass, before the finished image was fired again in the kiln. Many later medieval windows used clear glass with just dark painted outlines and shading, known as grisaille glass, from the French for grey, often with yellow stain for highlights. The strips of lead known as cames that held the glazing in place had a H-shaped profile, into which the pieces of glass were slotted and then cemented. Larger openings had additional support from iron saddle bars and stanchions metal rods embedded in the surrounding masonry which were usually connected to the lead cames by soldered wire.

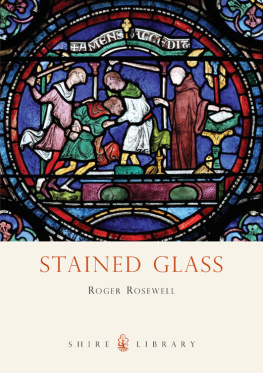

An example from the rare fifteenth-century medieval windows at Holy Trinity Church, Long Melford, Suffolk. Many medieval windows were later damaged and have since been reset with many fragments in random patterns.

The earliest pieces of stained glass discovered in Britain can be found at The Bede Museum, Jarrow Hall, South Tyneside, which were uncovered at the nearby monastery and probably date from the late seventh century, when it was recorded that the abbot ordered glass and glaziers from France. The oldest complete windows date from the late twelfth century, with the finest examples at York Minster and Canterbury Cathedral; ones that would later inspire Victorian designers. Over the following centuries, styles changed and techniques evolved, but stained glass windows remained a key element in the design of most churches until Henry VIIIs founding of the Protestant Church of England and the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s heralded a period of neglect and destruction. The images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, apostles and saints were revered Catholic idols that Protestants rejected, on the basis that in the Second Commandment God instructs that idols or any representation of him should not be made. Henrys son, Edward VI, passed legislation ordering that monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry and superstition, including windows, should be removed. In strongly Protestant areas some windows were lost; in others, a compromise of whitewashing the offending image might have sufficed. However, the high cost of re-glazing the damaged windows was soon appreciated, so under Elizabeth I stained glass gained a degree of protection. During the English Civil War in the 1640s, puritanical Parliamentarians, who viewed idolatry as a sin and the work of the Devil, set about destroying the surviving images in windows. Some were removed or received protection; others escaped because they were high up in the church or in remote parts of the country and out of reach of the iconoclasts. However, in Scotland and Ireland the destruction was more thorough, and virtually no medieval glass has survived here.