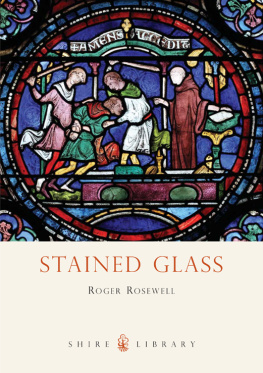

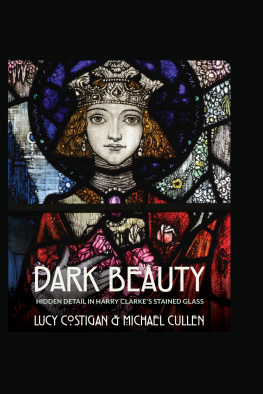

STAINED GLASS

Roger Rosewell

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

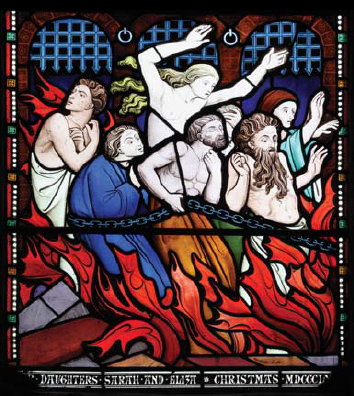

Detail from the Last Judgement by Clayton & Bell, 1860, St Mary, Hanley Castle, Worcestershire.

CONTENTS

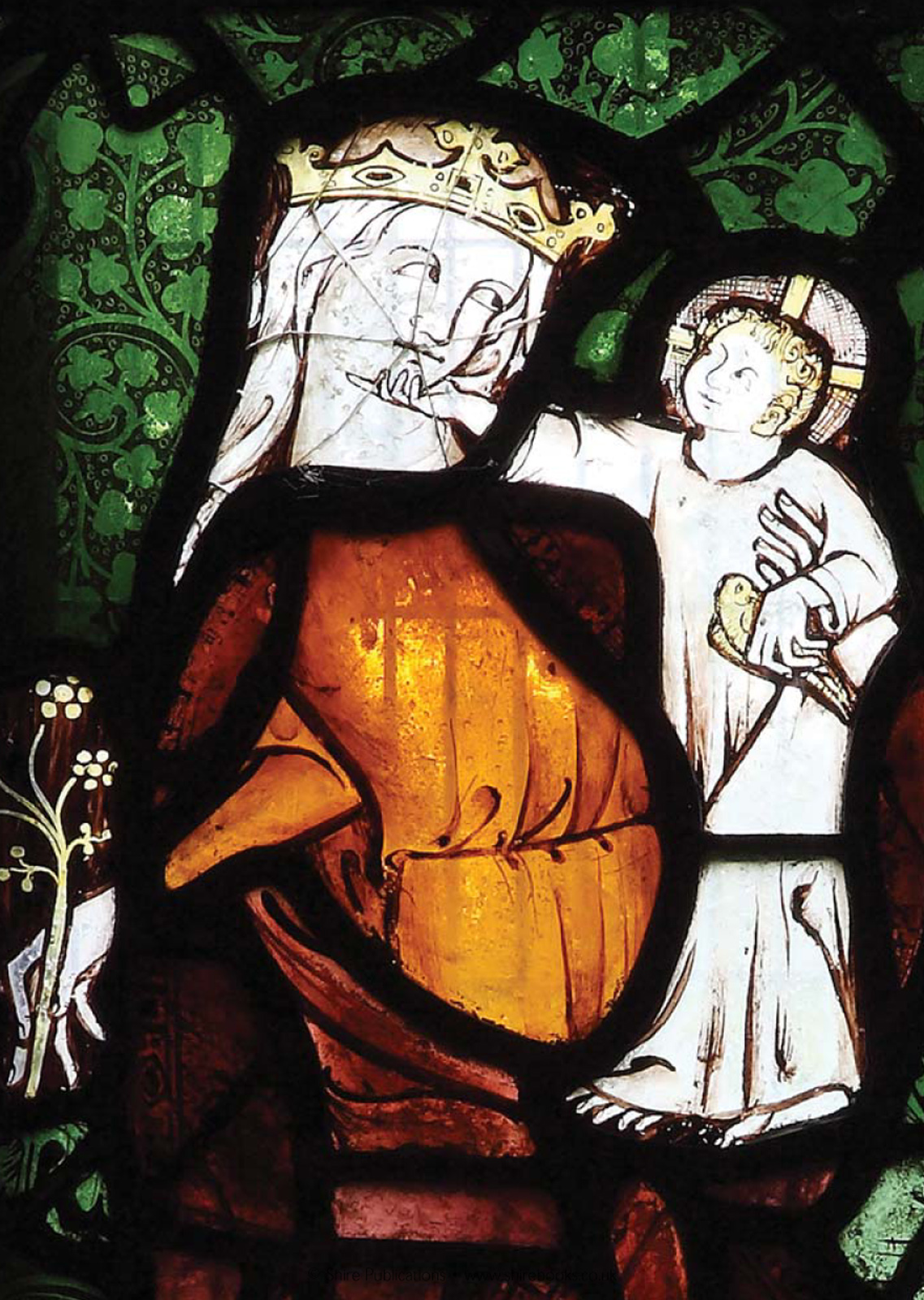

The Virgin and Child, c.13305, St Michael and All Angels, Eaton Bishop, Herefordshire.

INTRODUCTION

F OR OVER A THOUSAND YEARS painted and stained glass has filled the windows of English cathedrals and churches with sacred stories and vivid images of great moments in national history.

These masterpieces of colour and design were produced by artists who painted with light to create monuments that have inspired generations of audiences.

They include the largest collection of surviving medieval paintings in England and some of greatest masterpieces of modern art.

Whether small and delicate or towering and powerful, these windows transform buildings and change the way we see and feel.

Apart from their religious significance, stained glass windows also provide a dramatic record of the people whose beliefs and passions shaped England for a millennium. They are unique lights into our past.

gluttony, lust and sloth, from the seven deadly sins, fifteenth century, St Mary Magdalene, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire.

ANGLO-SAXON WINDOW GLASS, AD 7001066

T RYING TO PIECE TOGETHER the early history of stained glass is like looking through a misted window on a rainy day. Not everything is clear; much cannot be seen. A twelfth-century manuscript says that window glass was installed at York Minster as early as AD 66972 to prevent the entry of birds and showers, but for most historians the story begins a few decades later, during the construction of a new monastery at the mouth of the river Wear, now part of modern Sunderland. According to a near-contemporary account of these events written by the Venerable Bede, a monk at the adjacent twin monastery of Jarrow:

When the work [at Wearmouth] was drawing to completion, he [Abbot Benedict] sent messengers to Gaul [probably Normandy] to fetch glaziers, craftsmen who were at this time unknown in Britain, that they might glaze the windows of his church, choir and refectory. This was done and they came, and they not only finished the work required, but from this caused the English to know and learn their handicraft .

Over two thousand pieces of white and coloured window glass have been recovered by archaeologists from the Wearmouth and Jarrow sites. The colours include blue of several hues, green, amber, yellow-brown and red. Scientific analysis has shown that it was made from recycled broken glass, possibly salvaged from abandoned fifth-century Roman buildings, and chunks of raw glass imported from the eastern Mediterranean (modern-day Egypt, Jordan and Israel), the main centre of commercial glass production before the ninth century.

How this raw glass got to Northumbria remains a fascinating mystery. It is thought to have been exported from the Middle East to northern France before crossing the Channel and edging its way along the eastern coast of England by ship.

Once the glass had been unloaded, it was processed and cut into small shapes square, rectangular, triangular, diamond, and curved known as quarries. It seems likely that the separate pieces were then arranged into a decorative mosaic pattern, with the individual quarries held together by a framework of lead strips. Formed in H-shaped sections, these lead supports are known as cames (from the Latin calamus, meaning reed), and the lines they formed around the cut pieces of glass were often used as integral parts of the overall design.

At the Anglo-Saxon church of St Paul at Jarrow, some of the excavated fragments have been assembled in this manner and installed in a small circular window. It is a conjectured scheme, rather than a replica of any original design, and is the oldest window glass in England.

Apart from these finds, Anglo-Saxon window glass dating from the seventh to eleventh centuries has been recovered from sixteen other sites across England. A fragment excavated at Winchester, dated by archaeologists to c. AD 9661066, is painted with acanthus leaf foliage of the same type as appears in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts of the same period.

The origin of this later glass is unclear, as glass making had begun to spread to northern Europe about this time. Although there is virtually no evidence for the manufacture of glass in England in Anglo-Saxon times, the production of clear (white) glass was widespread in the Wealden forests of Surrey and Kent from the thirteenth to seventeenth centuries, and in Staffordshire from the early fourteenth century to the seventeenth century.

Anglo-Saxon glass, c. AD 700, St Paul, Jarrow, Tyne and Wear.

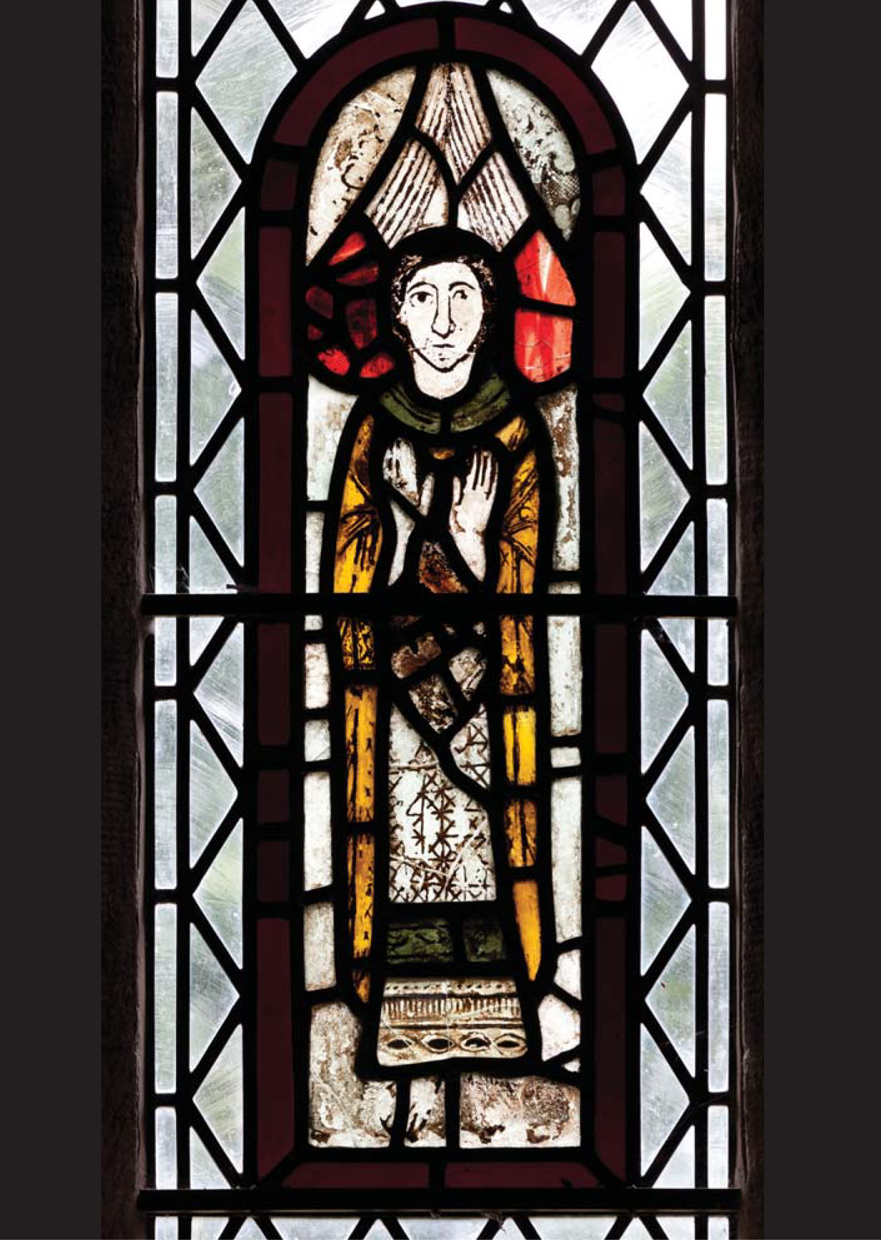

St Michael, c. 110035, in later setting, All Saints, Dalbury, Derbyshire.

THE NORMANS, 10661200

I N CONTRAST TO FRANCE, very little Norman painted glass survives in England from the hundred years after the Conquest in 1066. There is a small figure of the Archangel St Michael at Dalbury (Derbyshire) dated to c. 110035, and four windows in Canterbury Cathedral, possibly made around 115060. These are the earliest complete stained glass windows in England.

Both sets of windows incorporate pot-metal coloured glass, the description given to glass that was coloured during the production process by the addition of various metal oxides to the clay melting pot: iron oxide made red; copper oxide green or yellow; cobalt (aluminium oxide) produced blue; and magnesium purple. For reasons not entirely clear, these processes were never developed in medieval England and every piece of coloured glass used in church windows had to be imported, often from the Rouen area in Normandy, but also from Burgundy, Hesse and Lorraine. From the end of the fifteenth century Venetian glass was available in London.

Sadly the evidence for the next fifty years is again extremely scarce; it was a time of profound innovation in the architecture of churches and the display of stained glass. At the time of the Conquest, an art and architectural style based on Roman models, known as Romanesque, dominated Europe (in England it is often called Norman), in which walls were massive and window openings relatively small with rounded arches.

All changed when the great abbey church of Saint-Denis, near Paris, was rebuilt in the 1140s, and emerging new architectural ideas coalesced. The use of pointed arches and flying buttresses meant that walls could be opened up for tall lancet windows. For many Christian writers, such as an unknown twelfth-century German poet at Arnstein Abbey, streams of light passing through glass became a metaphor for Christs Immaculate Conception and his birth to a Virgin mother.