INTRODUCTION

A round 1207 a savage trial by combat was fought before a huge crowd in the northern English city of York. During the fight, the loser, a man called Ralph, was blinded by his stronger opponent. Weakened by his suffering and unable to see, he was subsequently stretchered to the shrine of one of the citys most famous former archbishops, St William, in York Minster, where, after he had prayed for the saints help, his eyesight was miraculously restored.

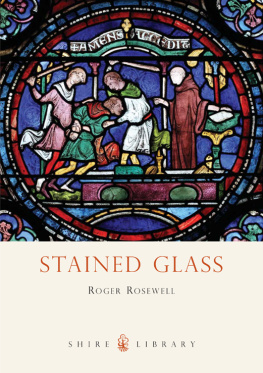

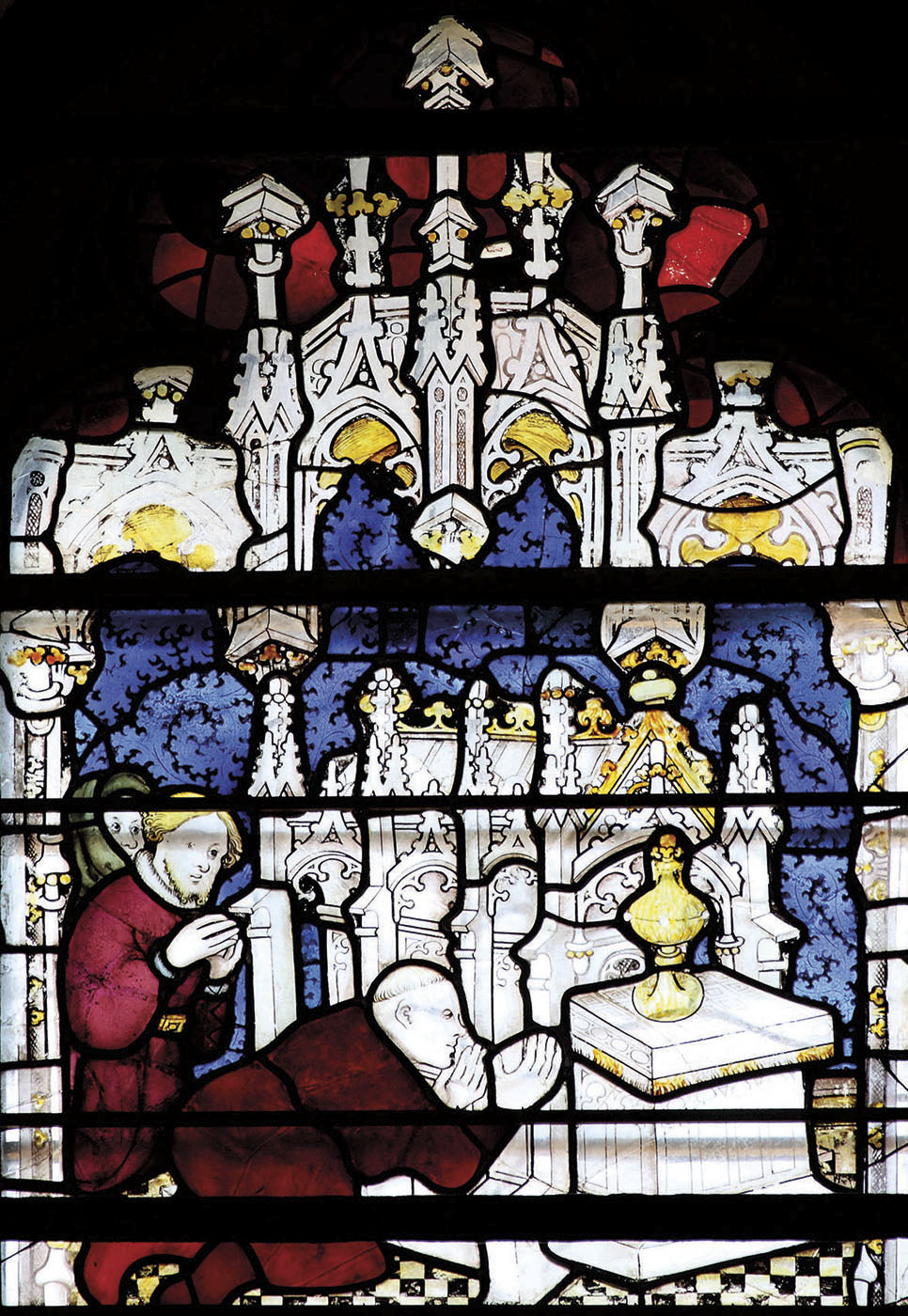

Detail of the legend of St Nicholas and The Cup in which a drowning boy is resuscitated by the saint. Stained glass window, c. 151019, in the Church of All Saints, Hillesden, Buckinghamshire.

Such amazing stories were not uncommon in medieval Britain. Similar accounts of lost eyes being regrown by the intervention of saints were told in Canterbury and Worcester, alongside reports of cures of various afflictions ranging from leprosy to paralysis, as well as rescues from wrongful imprisonment and unjust punishment. The power of saints to help effect miracles of these magnitudes was one of the staples of Christian spirituality. The Church taught that saints like William, who sat close to God in the holie company of heaven, were uniquely placed to intercede with him when humans asked for divine help. Rich and poor alike believed in these intercessionary powers for almost a thousand years, shaping and defining the lives of twenty generations.

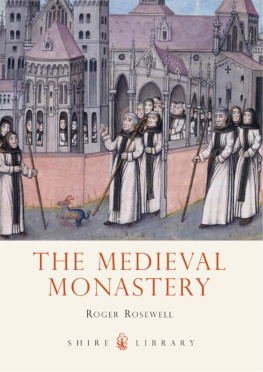

The stories of saints and their miracles were told by word of mouth, in manuscripts and through art such as stained-glass windows, wall paintings and drama. Churches were dedicated to God in their names. Kings carried their banners into battle. Every village or parish remembered them on special feast days where plays and other events re-enacted their lives and communities celebrated the protection of their powerful, if invisible, defenders and allies. Even the landscape was shaped by their stories and miracles. When young virgin girls, such as St Winefride in north Wales and St Sidwell in Exeter, were beheaded by wicked suitors or jealous relatives, holy wells were said to have sprung up where their heads fell. At Whitby in Yorkshire spiral fossil ammonites found in the rocks below the cliffs were said to be snakes that had been transformed into stone by the prayers of the seventh-century saint, St Hilda, a local abbess.

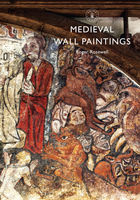

Late fifteenth-century rood-screen painting of St Apollonia holding a tooth in pincers in the Church of St Michael, Barton Turf, Norfolk.

Over time many saints achieved reputations for possessing special skills or areas of expertise. Favourites included St Apollonia, a Roman martyr whose teeth had been pulled out with pincers and who was consequently invoked to relieve toothache; St Nicholas of Bari (nowadays better known to many as Father Christmas) who protected children and seafarers; St Margaret of Antioch whose miraculous emergence from the belly of a dragon saw her adopted by mothers in childbirth; and St Eloi (sometimes Eligius, Eloy or Loye), a former goldsmith turned Bishop of Noyon, in northern France, whose shoeing of an uncontrollable horse possessed by the devil (he reputedly detached the leg, fixed the shoe and reattached the leg, while making the sign of the cross) saw him adopted by horse-traders and farriers.

Saints were an intrinsic part of daily life, loved and trusted by every social group. Pilgrimages to their shrines funded the building of great cathedrals and abbeys, and created networks of roads, hostels, and chapels across Europe, forking westwards to Santiago de Compostela in north-western Spain or eastwards via Venice and by ship to Jerusalem and the Holy Land in the eastern Mediterranean.

St Winefrides Well (151226), at Holywell, Flintshire, Wales.

For most of the Middle Ages, enduring beliefs in the miracles and intercessions of saints provided hope for those who sought relief from pain, sin and injustice. Saints were confidants and friends, helpers and protectors. Their lives were held up as models to follow devout, pious, pure, immune to temptation and evil; their virtues were employed as aides and inspiration; their mercy and strength were available to all.

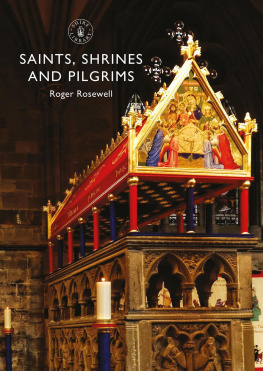

Stained glass in York Minster, c. 1414, depicting Ralph praying at the shrine of St William of York, after which his eyesight was miraculously restored.

Life was unimaginable without them.

SAINTHOOD

C hristian ideas about sainthood flowed from the experiences of the early Church. After the death of Jesus around AD 33, apostles such as St Paul travelled widely in the Roman Empire, preaching the new religion. At first most Romans were fairly indifferent but when suspicions grew that Christianity was a disloyal sect which posed a threat to the stability of the empire, sporadic waves of persecution erupted, especially during the rules of the emperors Nero (ruled AD 5468) and Diocletian (ruled AD 284305).

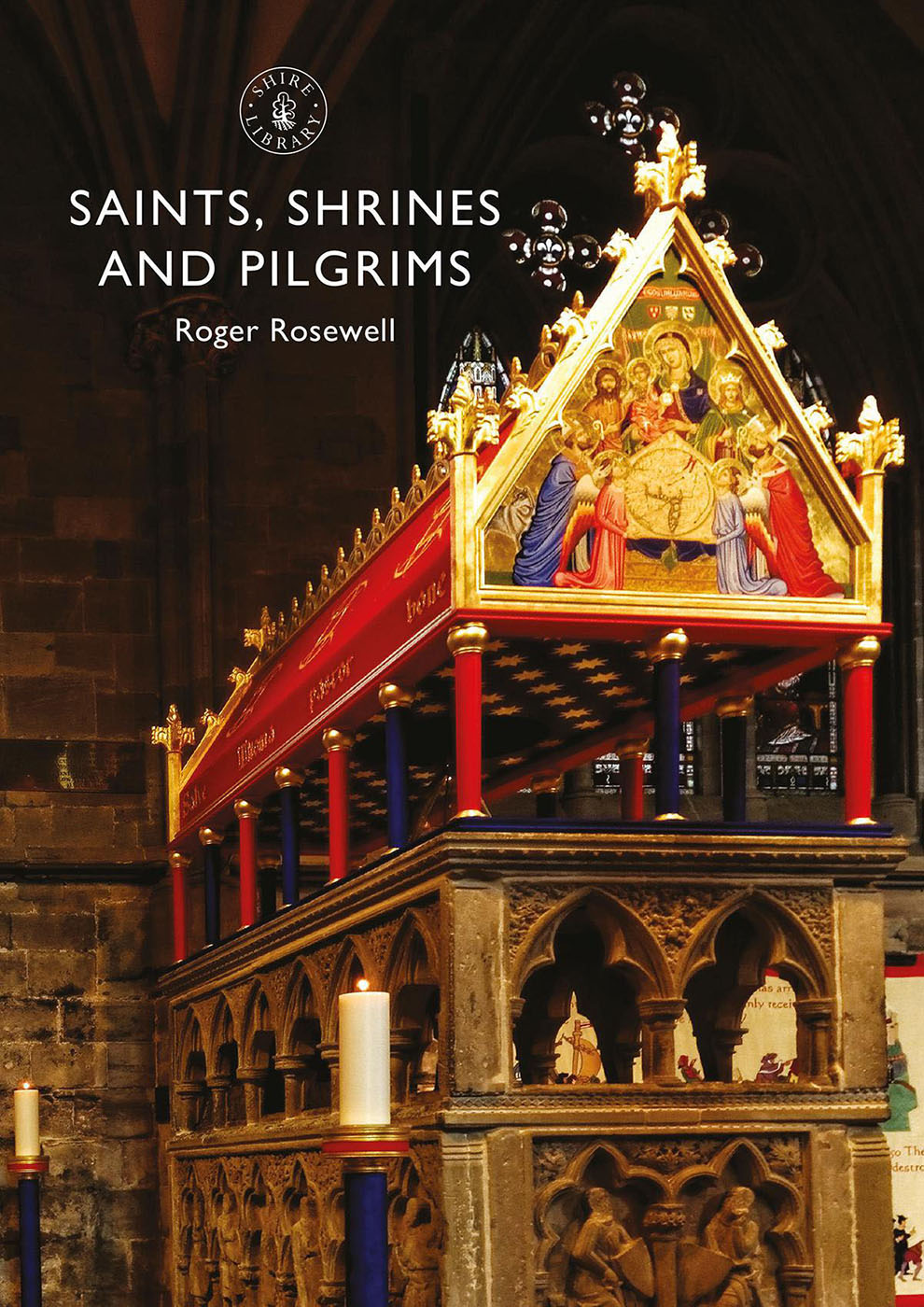

Fourteenth-century reconstructed shrine of St Alban, Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban, Hertfordshire.

Christians who survived these waves of terror revered those who had died for their beliefs, and built altars and churches over their graves. Many were commemorated in art holding a palm branch, representing the victory of the spirit over the flesh. The anniversaries of their martyrdoms were remembered by ceremonies which gradually evolved into a belief that, although apparently dead in body, such saints retained an active presence on earth via their relics (from the Latin reliquiae, meaning leftovers or remnants), which were either physical remains, such as bones, blood, teeth and hair, or secondary objects that had been in contact with them their clothing, dust from their graves, water that had washed their bones, and so on. In many cases the tombs or shrines which housed the bodies were regarded as the living homes of saints. Combined with prayer, such relics were seen as activating what has been called a holy helpline between earth and heaven in which saints would seek to persuade an all-powerful God to answer a supplicants prayers.

British Christianity was no exception to these ideas. As it became entrenched in England after the arrival of Augustine in AD 596, the Anglo-Saxon Church (roughly AD 6001100) embraced concepts of sainthood with enthusiasm. Older stories from the Roman occupation of Britain (AD 43410), such as the martyrdom of a soldier (later named as Alban), who had been killed during one of the persecutions, were recycled and embellished to include wondrous events such as the parallel death of the executioner who beheaded him and a well springing up where Alban had died. In the eighth century a Benedictine monastery was built nearby. During the later Middle Ages the shrine of St Alban attracted thousands of pilgrims and added to the wealth and influence of the abbey.