FURTHER PRAISE

FOR PILGRIMAGE IN ISLAM

An important contribution to the study of pilgrimage and to Islamic studies, Arjanas Pilgrimage in Islam avoids privileging seemingly normative readings of Islam. Rather, Arjana treats the word pilgrimage critically, not as a translation of the word hajj , but rather as a theme in the study of religion. The scope of this book, which considers Islam from a global perspective, along with its emphasis on theories of ritual and space, makes it an invaluable resource whether for the classroom or for the interested reader.

Cyrus Ali Zargar,

Associate Professor of Religion, Augustana College

Pilgrimage in Islam shows the wide range of pilgrimage practices in Islam in history and in the contemporary world, demonstrating that they are far more varied, dynamic, and non-sectarian than most previous accounts allow. By focusing on living traditions, Arjana helps to combat the static and old-fashioned presentations of Islam typically available. Clearly and engagingly written, this work will be of great value to students in courses in comparative religion as well as to students and scholars of Islam.

Theodore Vial,

Professor of Theology and Modern Western Religious Thought, Iliff School of Theology

Supplementing recent scholarship on the annual hajj, Pilgrimage in Islam helps readers think more capaciously about the array of sacred journeys Muslims have made over fourteen centuries. Sophia Arjana attends to material, textual, and technological dimensions of pilgrimage, and broadens restrictive understandings of what it means to study Islam.

Kecia Ali,

Professor of Religion, Boston University

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sophia Rose Arjana is an independent scholar who has taught at Iliff School of Theology, University of Denver, and the University of Colorado. Her published work includes chapters and articles on Shii pilgrimage architecture, liberation theology, Islamophobia, and Muslims in popular culture. Her first monograph, Muslims in the Western Imagination , was a CHOICE Outstanding Academic Title of 2015. She has traveled extensively in Muslim-majority countries, visiting pilgrimage sites in Iran, Turkey, Syria, Egypt, and Indonesia. She lives in Boulder, Colorado.

FOUNDATIONS of ISLAM

Series Editor: Omid Safi

Other Titles in this Series

Hadith: Muhammads Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World by Jonathan A.C. Brown

The Quran: An Introduction by Anna M. Gade

Shariah Law: An Introduction by Mohammad Hashim Kamali

CONTENTS

There are places, objects, and people where the veils between this world and the other worlds become quite thin. For a few breaths, it seems as if lightning flashes, and a darkened sky lights up. The boundary between this world and others is revealed as what it was all along: porous. These people, places, and objects are said to contain barakah , a Divine force that is palpable to all those who have hearts. The God of the infinite cosmoses shows up nearby.

This is one purpose of pilgrimage. We journey to find what has been with us all along. We find the presence that has been with us, inside us, around us, all around. But we have to go on the journey to find the treasure we have been sitting on. When we return, we are transformed, no longer who and what we had been before. Ultimately, pilgrimage is not to a place, but to a different state of being.

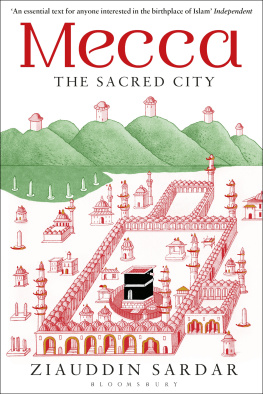

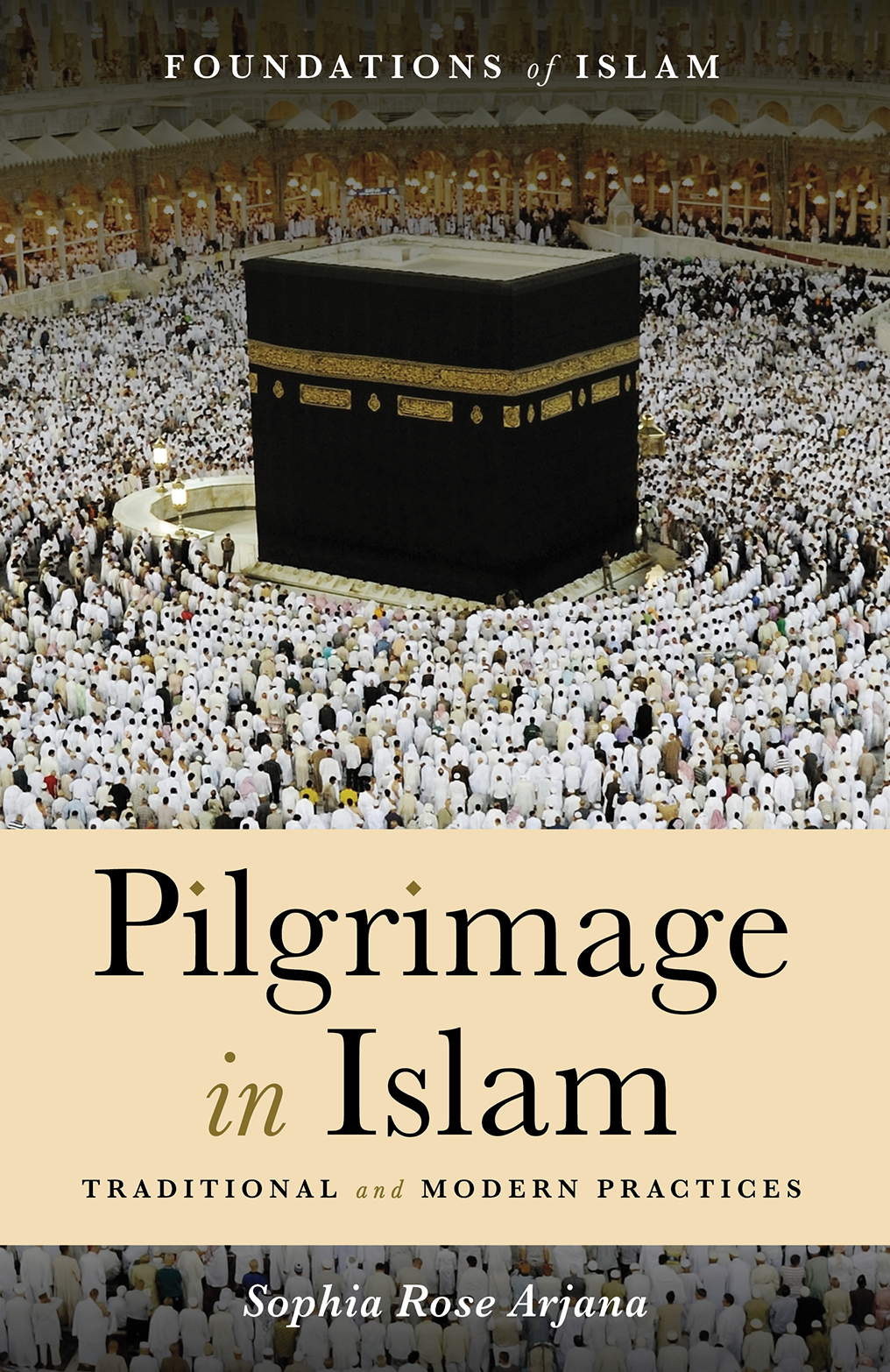

All religious traditions involve some notion of pilgrimage. In Islam the major pilgrimage, the hajj , is well-known, as we retrace the footsteps of a slave woman, Hajar, and reconnect to the Abrahamic foundations of faith. The pilgrimage to Mecca is even listed as the fifth pillar of faith. We come from the periphery of existence to the center, to the center of the center which is to say the heart. Standing at the marrow of the universe, we are one, and connected to the One.

Every year, millions of Muslims gather in Mecca for what is, for most of them, a once in a lifetime pilgrimage. The hajj is intimately private and unavoidably communal at the same time. They, we, have come from every background, every race, every class. The hajj has become something of a Rorschach test for Muslims and for the world: we see in it whatever we imagine about Islam and Muslims. To so many, it is the ultimate symbol of Muslim unity, where white and black, yellow and brown skins stand shoulder to shoulder, united before the One. To others, it is a symbol of how the consumerist capitalist culture, symbolized by the high-rise luxury hotels over Mecca, have thwarted and distorted the radical egalitarianism of Islam. Some see a fabulous exchange of the richness of Muslim cultures, food, learning, and stories. Others see a chance to express geopolitical tensions.

Every one of those pilgrims walks in the footsteps of a black woman, a maiden or a slave (depending on the story you prefer), a woman left in Gods care, or abandoned by a husband, a co-wife, or the victim of Sarahs jealousy. Every pilgrim walks in the footsteps of our mother Hajar/Hagar, a noble, tired, exhausted woman living as a single mother in the desert, without family, without support, without money, without water

Death was close.

God was closer.

She clutched her son so close that he breathed the air she breathed.

Her faith in God, and love for her baby, saved them both.

Hajar/Hagar figures differently in the Bible than she does in the Quran, partially because of how differently Isaac and Ishmael fare in the two scriptures. The Bible was written by the descendants of Isaac. So Ishmael and his mother Hagar, the stranger, are cast out. In the Quran, Isaac and Ishmael are both Gods prophets, and both Sarah and Hajar/Hagar are treated as wives of Abraham. Yet this much is agreed upon: Abraham left Hagar and Ishmael in the desert.

Here is how the story of Hagar is told in the biography of Muhammad:

It was not long before both mother and son were overcome by thirst, to the point that Hagar feared Ishmael was dying. According to the traditions of their descendants, he cried out to God from where he lay in the sand, and his mother stood on a rock at the foot of a nearby eminence to see if any help was in sight. Seeing no one, she hastened to another point of vantage, but from there likewise not a soul was to be seen.

During pilgrimage, all the pilgrims engage in a ritual called Say , where they rush between the hills of Safa and Marwa, quite literally tracing the footsteps of Hajar. On the hajj we are reminded that we dont merely have faith, we do religion. Religion is ritual, ethics, history, myth and mysticism all mingled.

Countless pilgrims to Mecca have detailed their experiences on this journey, few more famously than Malcolm X. The telling and re-telling of these pilgrimage stories themselves stand at the very formation of communal identity.

Yet, as significant as the pilgrimage to Mecca is, it is not the only place that the boundary between this world and the other world is thin. Over the centuries, millions of Muslims have been unable to travel to Mecca and Medina to experience God there. For many, it was simply too expensive, too far. Is it not the case that so many of the most tender and lovely poems in praise of the Prophets Medina have been written by far-away lovers who had to bring Medina to the heart, because they knew their feet would never walk on its soil? So they went, and they continue to go, to local vicinities where God is nearby. They come to places that are nearer, more intimate, more familiar, where the sacred speaks in a vernacular.