I am grateful, as usual, to my friend Merryl Wyn Davies for her invaluable help in researching and writing this book. Ehsan Masood provided beneficial advice on various drafts; and M. A. Qavi, apart from providing useful reference materials, gave constant (sometimes nagging) encouragement. Thanks are also due to all my former Hajj Research Centre colleagues: Sami Angawi, visionary architect and Director of the Centre; James Ismail Gibson, town planner; Mohammad Jamil Bronson, urban geographer; Bodo Rasch, world expert on tent cities; Peter Endene, transport engineer; Zafar Malik, artist and designer extraordinaire; Saleem ul-Hassan (aka Tabligh), statistician and data cruncher; and the late Zaki Badawi, the Centres expert on theology and Shariah. Wasiullah Khan, Chancellor, East West Univsity, Chicago, kept me amused during more challenging days in the holy areas. Finally, special thanks to Abdullah Naseef, the former President of King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah, for always being there.

ZIAUDDIN SARDAR was born in Pakistan and grew up in Hackney. A writer, broadcaster and cultural critic, he is one of the worlds foremost Muslim intellectuals and author of more than fifty books on Islam, science and contemporary culture, including the highly acclaimed Desperately Seeking Paradise . He has been listed by Prospect magazine as one of Britains top 100 intellectuals. Currently he is the Director of the Centre for Postnormal Policy and Futures Studies at East West University, Chicago; co-editor of the quarterly Critical Muslim ; consulting editor of Futures , a monthly journal on policy, planning and futures studies; and Chair of the Muslim Institute in London.

ZiauddinSardar.com

Desperately Seeking Paradise: Journeys of a Sceptical Muslim

Balti Britain: A Provocative Journey Through Asian Britain

The Consumption of Kuala Lumpur

The A to Z of Postmodern Life: Essays on Global Culture in the Noughties

Breaking the Mould: Essays, Articles and Columns on Islam, India, Terror and Other Things That Annoy Me

The Future of Muslim Civilization

Islamic Futures: The Shape of Ideas to Come

Reading the Quran

Muhammad: All That Matters

What Do Muslims Believe?

Introducing Islam

The No Nonsense Guide to Islam (with Merryl Wyn Davies)

The Touch of Midas: Science, Values and the Environment in Islam and the West

Explorations in Islamic Science

The Revenge of Athena: Science, Exploitation and the Third World

Thomas Kuhn and the Science War

Information and the Muslim World

Hajj Studies

An Early Crescent: The Future of Knowledge and Environment in Islam

Introducing Chaos

Introducing Mathematics (with J. R. Ravetz)

Introducing Philosophy of Science

Muslims in Britain: Making Social and Political Space (with Waqar Ahmad)

Muslim Minorities in the West (with S. Z. Abedin)

Orientalism

Postmodernism and the Other

Aliens R Us: The Other in Science Fiction Cinema (with Sean Cubitt)

Cyberfutures: Culture and Politics on the Information Superhighway (with J. R. Ravetz)

The Third Text Reader on Art, Culture and Theory (with Rasheed Araeen and Sean Cubitt)

Barbaric Others: A Manifesto on Western Racism (with Merryl Wyn Davies and Ashis Nandy)

Introducing Cultural Studies

Introducing Media Studies

Introducing Postmodernism (with Richard Appignanesi et al. )

Rescuing All Our Futures: The Future of Future Studies

Future: All That Matters

Islam, Postmodernism and Other Futures: A Ziauddin Sardar Reader

How Do You Know? Reading Ziauddin Sardar on Islam, Science and Cultural Relations

Why Do People Hate America? (with Merryl Wyn Davies)

American Dream, Global Nightmare (with Merryl Wyn Davies)

Will America Change? (with Merryl Wyn Davies)

A first bright glimmer of dawn lit the horizon, the cool breeze giving way to dusty heat. A man stood still in the long, loose folds of his garments, watching as a small group of people made haste towards the central part of the city. He observed them enter a circular arena containing a cubic structure surrounded by statues. He watched as they passed the idols, and, one by one, bowed down to kiss the largest, a red agate bust known as Hubal.

The man turned away from this familiar scene to resume his journey. He walked past a family, including a small child wrapped in muslin, on its way to the cemetery. He could hear the approaching sounds of a caravan bustling into the city and moved to avoid it. Camel after camel, loaded with spices and silk, wine and perfume, loped its way to the market, followed by a long line of slaves trudging in single file. The noise and the odour of aromatic liquids filled the air. The city was now stirring. The man continued on his way towards a mountain northeast of the city. In less than an hour he was negotiating its gentle lower slope. When he reached the point where the gradient rises abruptly and the climb becomes more difficult, he stopped. Standing erect, he turned and looked towards the city below, surrounded by mountains from all sides. He was looking at Mecca.

The mans name was Muhammad. He was in his early forties and of medium stature. Though his complexion was fair, where his body had been exposed to the elements he was tanned to a reddish hue. He had a slightly rounded face, a wide forehead and thin but full eyebrows. His curly hair, parted in the middle, tumbled around his neck.

Mecca has had many names. It was known as al-Balad : simply the main city, as it was a key urban centre and market town. It was known as al-Qaryah : a place where large numbers of people congregate like water flowing into a reservoir. And as the Baca of biblical times it is mentioned in Psalms 84: 56:

Blessed are those whose strength is in you, who have set their hearts on pilgrimage. As they pass through the Valley of Baca, they make it a place of springs; the autumn rains also cover it with pools.

Some associate Baca with a balsam tree; a gum-exuding (weeping) tree; or weeping wall-rocks. The Arabic form of Baca, Bakkah, can be translated as lack of stream. The valley was indeed a dry place with no vegetation. The Greeks translated Baca as the Valley of Weeping. This Valley of Baca had strong associations with lack of water and deep sorrow, a place of lament. Yet, when the righteous passed through the valley, they could make it a place of springs, a source of life.

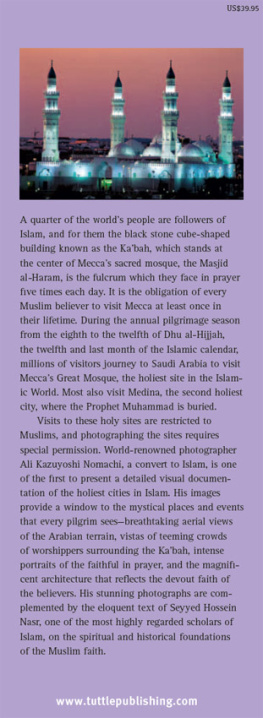

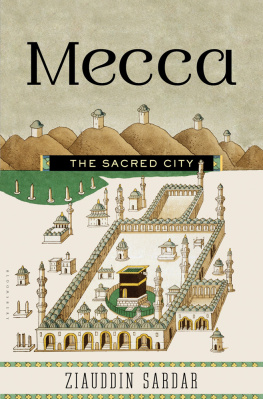

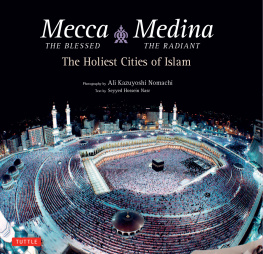

The focal point of pilgrimage in the Valley of Baca was a structure known simply as the Cube, or in Arabic, Kaaba. Forensic linguistics is littered with examples of a common phenomenon that occurs in many languages: this is the replacing, adding or subtracting of single letters in place names over time. London, for example, was originally called Londinium when the city was first established by the Romans. In the case of Mecca a shift took place from one labial consonant to another, from B to M, and Baca, in Arabic Bakkah, came to be called Makkah, or English Mecca.

The inhabitants of the city were once known as the Aribi, a term that makes its first appearance in a cuneiform account of the Battle of Qarqar (853 bce ) by the Assyrian king Shalmanesar III. It means nomad or desert dweller. In the sculptures dating back to this period, many discovered recently in tombs and cemeteries in northern Saudi Arabia, the Arabs have oval faces, large straight noses, small chins and huge eyes. The eyes, with dilated pupils (inlaid with black stones or lapis lazuli), hint perhaps at religious stupor. Or are they an indication, perhaps, of the widely held belief in the region that spiritual power resides in the faculty of sight? A beneficial look would induce bliss, an evil eye could kill.

Mecca was not the only major city in the region. The oasis of Taif lies sixty miles to the south, known as the Garden of the Hijaz for its vines, fruits and vegetables. Just over 200 miles to the north of Mecca is the city of Yathrib, which in Muhammads time was home to Jewish clans renowned as goldsmiths and home to scholars familiar with the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud. And around sixty miles southwest is the port of Jeddah, the gateway to the world outside. Apart from the Kaaba, Mecca had another advantage over these cities: it stood at the junction of two major global trade routes. The first went northsouth, through the mountains of the Hijaz. To the south it went to Yemen, where it linked with the trade coming across the Indian Ocean from India and Southeast Asia; and northwards it went to Syria and the Mediterranean littoral. The second route went eastwest. The eastern route ran through Iraq and on to Iran, Central Asia and eventually China; the western route connected to Abyssinia, the Red Sea ports of Egypt and eastern Africa.

Next page