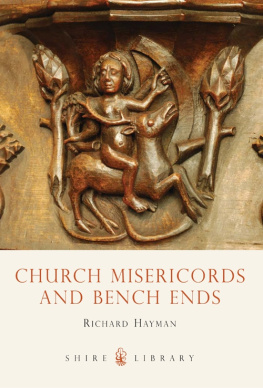

CHURCH MISERICORDS AND BENCH ENDS

Richard Hayman

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A man kneels at a bench and prays, on the armrest of a bench at Stowlangtoft (Suffolk).

I N LUDLOW CHURCH (Shropshire) is a carving on a fifteenth-century misericord of an owl. Todays audience would probably misinterpret it by assuming that the owl is intended as a symbol of wisdom, whereas it meant exactly the opposite. The image would have been familiar to those who first saw it, and its meaning well understood. It came from the bestiary, a compendium of animals with their moral attributes, in which the owl stood for ignorance and, more specifically, for the Jew who preferred darkness to the light of Christianity. On either side of the owl are two subsidiary carvings, known as supporters, that depict smaller birds mobbing the owl, the manner in which illustrated books portrayed it. Of the owl the Bestiary notes that if other birds see it, they set up a great clamour, and it is vexed by their fierce onslaughts. So when a sinner is recognised in full daylight he becomes an object of mockery for the righteous.

The Ludlow owl demonstrates how, in the Middle Ages, images were invested with moral and spiritual meaning. At a time when the populace was illiterate, sermons were few and mass was said in Latin, people lived in a highly visual culture. Images of various forms were integral to medieval Christianity until they were swept away during the Reformation of the mid-sixteenth century, when the word replaced the image as the principal form of expression. One of the ways in which this rich culture can still be appreciated is in the carvings applied to choir stalls and the ends of common pews, usually referred to as bench ends. As works of applied art misericords and bench ends allowed people to express their piety in the Christian faith; they were an opportunity for patrons to display their wealth and status; and they were an outlet for the spirit of tomfoolery and social satire that were as much a part of the Middle Ages as religious devotion.

Misericords were hidden beneath the seats of the choir stalls and were seen only by the priests who used them. They have been likened to the margins of medieval manuscripts, where humorous and pious asides were made to the main subject matter. As conventional subjects occupied the main foci of walls and windows, misericords were sometimes literally a place for toilet humour on the side. Bench ends were marginal in a less satirical sense, when we consider the context of the medieval churches in which they were housed. Sculpture, stained glass and wall painting were the principal means for conveying the faith in churches, including images of saints, narrative scenes such as the life of the Virgin Mary and the Doom, or Day of Judgement, painted on the east wall of the nave. Bench ends and misericords were used to express many images that were not otherwise prevalent on the walls and in the windows.

The sun on a misericord at Ripple (Worcestershire).

Coarse humour is abundant on misericords. At Gresford (Wrexham) an acrobat flaunts his bare backside.

In this mid-fifteenth-century misericord at Ludlow (Shropshire) an owl, representing the Jew, is mobbed by two smaller birds to the left and right.

A man holds up the misericord and its occupant at Kings Lynn St Margaret (Norfolk).

The marginal artistic status of bench ends and misericords has been an important factor in their survival. Our heritage of medieval painting, glass and sculpture was largely destroyed during the Reformation by Act of Parliament, by a Protestant Church that distrusted images and the manner in which they were revered. Misericords and bench ends therefore have an increased importance in giving us a glimpse into a world of saints and demons, and the everyday world of thatchers, windmills and angry wives. Furthermore, their distribution is so widespread that they can be found in all sorts of places of worship, from the great cathedrals to the humblest parish churches.

MISERICORDS

A misericord of around 1380 at Hereford All Saints features a double-bodied lion with the head of a crowned and bearded man. The misericords in the church are notable for their symmetrical design, and this one is in a stall with carved arm rests and restored canopy.

T HE SEATS in medieval choir stalls were hinged so that when tipped up they revealed a bracket wide enough to sit on. The bracket is known as a misericord, derived from the Latin misericordia (meaning pity) and alluding to the original function of the ledge as a mercy seat. The rule of St Benedict, introduced in the sixth century and the foundation of western monasticism, required monks to sing the daily offices of the church Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers, Compline standing up. Only for the Epistle and Gradual at Mass, and the Response at Vespers, were they able to sit. Older monks adopted a leaning staff or crutch to help take the weight off their feet during the long hours they spent in the choir stalls. By the eleventh century the misericord was introduced to enable monks to rest against the ledge of the misericord, thereby giving the impression of standing while in reality sitting.

The earliest mention of misericords appears in the eleventh century in the rules of Hirsau monastery, Germany. They were attached to the upper rows of the choir stalls and were reserved for the older monks. Misericords subsequently existed throughout Western Europe, except in Italy. We do not know when misericords first appeared in Britain, but at Canterbury Cathedral wooden choir stalls perished in a fire in 1174. The earliest surviving examples at Hemingborough (North Yorkshire), Christchurch (Dorset), Kidlington (Oxfordshire) and Durham Cathedral belong to the early thirteenth century. Salisbury Cathedral has a set made after 1236, while the set made for Exeter Cathedral around 1250 is the first in which the misericords have figurative carvings.

Most misericords in Britain are later, and they continued to be made until the Reformation, when the English church broke with Rome and monasteries were dissolved. Many of the surviving sets of misericords in cathedrals and monasteries were second-generation sets connected with rebuilding work. For example, at Wells Cathedral the original choir stalls with misericords were in a ruinous condition by the 1320s and the present set replaced it in the 1330s, after the new chancel was built. Likewise, Ripon Cathedrals misericords were installed after the rebuilding work made necessary by the collapse of the central tower in 1458. One of the misericords there is dated 1489.