I AM HAPPY to admit to the reader that this book contains a great deal of bias towards sites in East Anglia and the south of England. While it is certainly true that East Anglia contains almost as many medieval churches as the rest of England taken as a whole, with more than 650 in the county of Norfolk alone, the real reason is far simpler. The recent church surveys from which many of the examples for this book are drawn began in Norfolk and the eastern counties, and that is where we have most information from. This does not, of course, mean that there arent other fantastic examples of medieval graffiti to be found in churches all over Britain; there undoubtedly are. Its simply the case that nobody has really looked for them yet. They are all out there just waiting to be discovered after centuries of hiding in the shadows

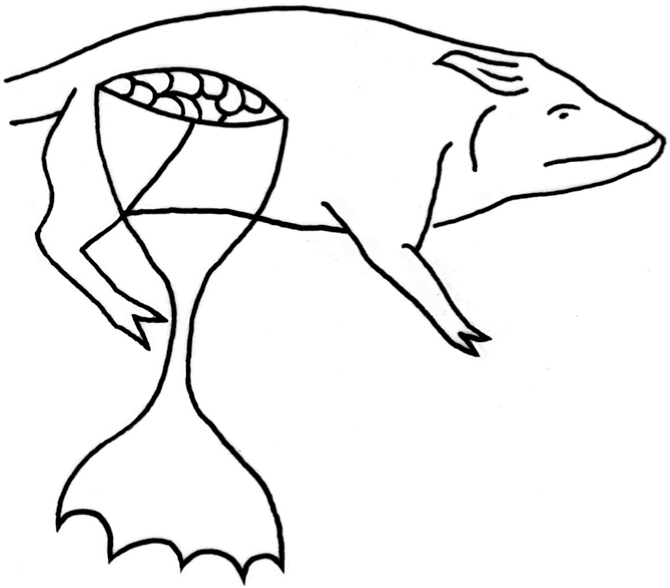

Pig and a chalice, Weybread, Suffolk

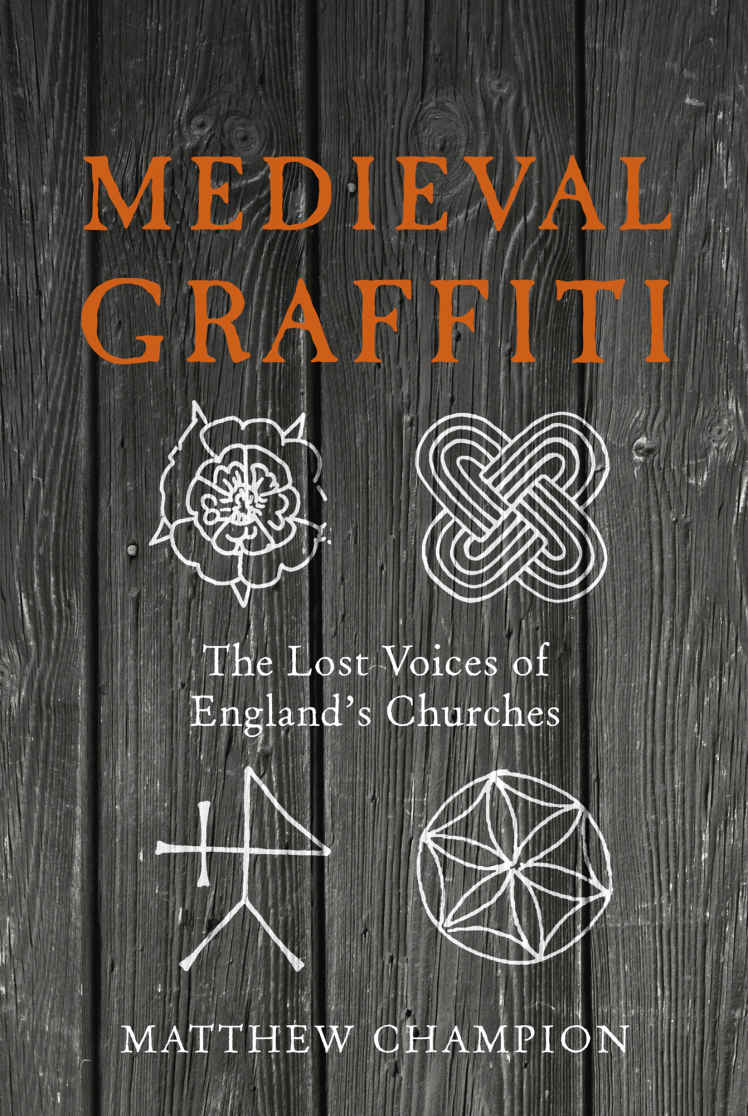

THE CHANCES ARE that if you read a newspaper story or magazine article that includes the words church and graffiti in the same sentence then the ending is unlikely to be a happy one. In the modern world, graffiti is widely regarded as both anti-social and destructive. It is seen as unacceptable behaviour that blights our streets, underpasses and railways with largely meaningless daubs of paint. The few artists who have moved beyond this level, to create stunning examples of contemporary street art, are largely the exception that proves the rule. Few people today could find any justification for leaving their mark scrawled across the stonework of a medieval church. Graffiti, to modern eyes, is nothing more than vandalism. Why, then, should the graffiti of the past be seen as any different? Why should the scratchings of our ancestors on the very fabric of their own parish churches be regarded as having any importance? Why should we devote time to discovering and recording ancient acts of anti-social destruction?

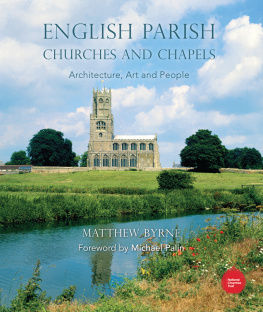

The simple answer is that ancient graffiti offers us something that most other areas of medieval and church studies cannot give us. It offers us a window into the medieval world, and the minds of those who created it. In particular, it offers us a rare glimpse of the lives of those who worshipped in the parish church; lives that otherwise have left almost no marks upon the world that they inhabited. Put simply, if you were to walk into one of the many hundreds of medieval churches that survive today, the chances are that you would come across a great many medieval survivals; carved bench-ends, colourful medieval wall paintings and shimmering stained glass. However, all these wonderful survivals tend largely to relate only to the parish elite. The coloured glass of the medieval church window and the dull brasses laid into marble upon the floor rarely carry images of peasants ploughing they show instead the rich lords of the manor in all their finery; donor images kneeling before the Blessed Virgin herself or martial figures lying stiff in coat armour. Essentially, the inside of our churches are monuments to those who could afford to be memorialised in such a manner. Where, here, is the voice of those who worked the parish land, who carried the stones to build the church itself, and worshipped in this splendid monument to their betters?

The medieval parish church represented far more than just a place of religious worship, acting also as a focus for both community and social life within the village. It was a symbol of local pride, of church authority and religious salvation. Whatever its geographical location within the parish, the church building formed the central core of parish life. For the lower orders of the parish, life within the community began at its font, marriages took place within its porch and vigils for the dead were held beneath its roof. And yet, despite playing such a fundamental role in the rites of passage of countless generations of commoners, we still know very little of how these individuals, the vast majority of the medieval congregation, actually interacted with the church on a physical level. Their voice is largely silent. The voice of the commoners does turn up occasionally, in manor court records, legal documents and wills, but these documents are, in my opinion, rather atypical. They represent specific moments in time when those individuals came into contact with authority; the authority that ordered the medieval world. As such, they do not, and can not, truly reflect the attitudes and opinions of those people to their church, as either a building or an institution. Their voice has been muted by the constraints of authority.

It is in these areas of study, looking for the lost voices of the medieval village, that graffiti can play a crucial part. The images and texts that are inscribed into the very stones of the church building can often tell us far more about the medieval people who worshipped there than any amount of brightly coloured stained glass. Indeed, graffiti has the almost unique distinction of being able to be created by almost every class within the medieval parish. From the lord of the manor and parish priest to the lowliest commoner and peasant; all could, and did, leave their mark upon the church building. Far more than the idle scratching of bored choirboys, the medieval graffiti that we discover in churches today tells us about all aspects of the medieval world. It tells tales of grief and loss, of love and humour. At times, it speaks to us of religious devotion and fear of damnation. It carries names of long-dead children across the centuries, records happy days of pageants and celebrations. In extreme cases, it tells us of events so dreadful and terrifying that those who were there to witness them believed that their own God had forsaken them, and that Judgement Day was coming fast upon them. In short, it tells us of life. Life and death in an English parish many hundreds of years ago.