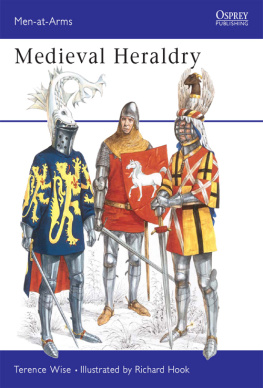

Men-at-Arms 99

Medieval Heraldry

Terence Wise Illustrated by Richard Hook

Series editor Martin Windrow

Contents

Medieval Heraldry

Introduction

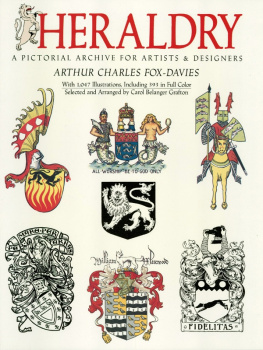

It is not the aim of this book to describe in precise detail the rules of heraldry, but rather to introduce the reader to the rle of heraldry and to provide examples of how it was used in the 14th and 15th centuries. Therefore, it is recommended that any reader lacking knowledge of the basics should have at hand an introductory book on the subject, such as the Observer Book of Heraldry, published by Warne.

It is anticipated that most readers of this book will be military enthusiasts, modellers and wargamers, and therefore I have concentrated on the purely military aspect of medieval heraldry. This is appropriate, as we are concerned here with a period of history during which heraldry retained one of its original functionsthe identification of individuals and their followers on the field of battle. Matters such as mottoes, supporters, achievements, the arms of unmarried ladies, hatchments, and civil, ecclesiastical and corporate coats of arms have been omitted. Readers wishing to learn about these facets of the subject are referred to the Observer title, and to an interesting booklet entitled Civic Heraldry, published by Shire Publications. In place of these subjects readers will find more information on military matters, such as liveries, badges, crests, surcoats and horse trappers, than is normally found in books on heraldry.

Most books written by English authors almost totally ignore continental heraldry, and therefore an attempt has been made to include at least some European examples. However, almost inevitably the emphasis will be found to be on English heraldry, mainly because the various sources are more readily available to an English author, but also because drastic political changes in many European countries have caused the abolition of the Colleges of Heralds and the scattering or loss of their records. (The records of Polish medieval heraldry, for example, were destroyed during the Second World War.) It should also be remembered that most publications on European heraldry have not been translated into English, rendering much information inaccessible, for although many people can read French or German, and perhaps some Italian or Spanish, few can read Dutch, Polish, the Scandinavian languages, or medieval Latin.

English writers also usually overlook the fact that, once coats of arms had been adopted by the nobility, the lower orders in some European countries also began to assume coats of arms, and continued to do so until heraldry no longer had a purely military rle. French sources quote many examples of bourgeois bearing arms in the 13th century, and by the end of that century this practice was widespread. From the bourgeois of the towns the bearing of arms spread to the peasants of the countryside, and the earliest known example of such arms in France occurs in 1369 (the arms of Jacquier le Brebietthe shepherd: three sheep held by a girl).

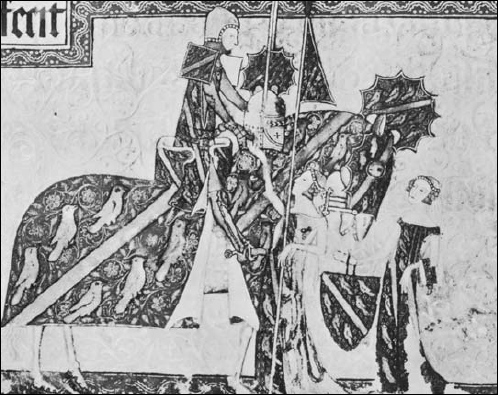

The effigy of John Eltham, Earl of Cornwall, in Westminster Abbey, circa 1334. He was the son of Edward II and bears the arms of England differenced by a bordure of fleurs-de-lys, his mother being Isabel of France. His shield is heater type.

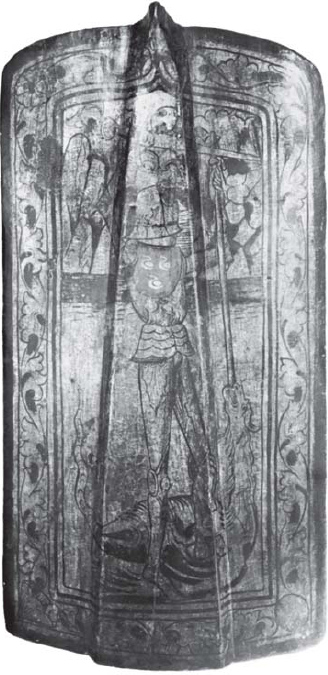

Another form of shield which remained in continuous use throughout the medieval period was the pavise, which could be propped up to provide cover for an archer or crossbowman. It was normal to paint these shields, and this example bears the arms of the town of Zwickau: St George bearing a shield on which are painted three swans. It is dated circa 1480.

Unlike the class system of England, in France Unlike the class system of England, in France the nobility and bourgeoisie were not rigidly separated, but it should be remembered that the bearing of arms did not convert a bourgeois into a noble. Some nobles were indeed bourgeoisie, but they had to be sure to state their origins. One definite form of distinction was that neither bourgeoisie nor peasantry were entitled to wear helmet crests.

Portugal and Germany were two other countries in which burghers and peasants were allowed to bear arms: in the latter even the Jews were permitted coats of arms, an unusually liberal practice in those days of rabid bigotry. Members of the lower classes in Portugal were forbidden the use of silver or gold in their arms, and in 1512 King Manuel I forbade the use of arms by all those not classed as nobles.

On Heraldry and Heralds

It is as well to begin by defining precisely what is meant by the word heraldry. Dictionaries usually refer to it as the art of the herald or, more helpfully, the art or science of armorial bearings, armoury being the medieval term for heraldry (Old French armoirie); but heraldry is perhaps best described as a system for identifying individuals by means of distinctive hereditary insignia, this system originating in western Europe during the Middle Ages. From archaeological sources we know that insignia have been used on the shields of warriors to identify individuals in battle since classical timesas early as circa 800 B.C. the Phrygians were using geometric and stylized floral designs on their shieldsso what is it that makes medieval heraldry unique? The phrase distinctive hereditary insignia contains the key, for all true heraldry is hereditary, that is the insignia are inherited without alteration by the heirs of the former bearers.

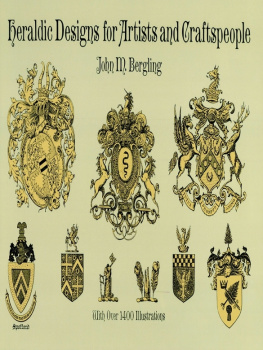

As far as can be ascertained, heraldry first appeared about the middle of the 12th century and flourished during the 13th and 14th centuries. The shapes of the shields used during these centuries made it necessary for the heralds and painters to adapt the natural forms used as insignia to fit irregular spaces, and the insignia therefore assumed a symbolic rather than natur-alistic appearance. Any study of heraldry soon reveals a considerable difference between the simple forms used in the early days and the more perfect and intricate forms of the later days. The almost ascetic style of the early years identifies the true medieval heraldry.

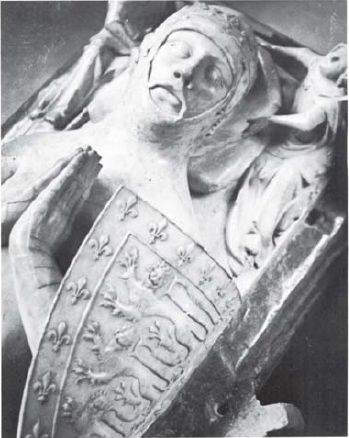

The effigy of a member of the Bowes family in the church of Dalton-le-Dale, Co. Durham, showing the tight-waisted jupon. The arms are another example of canting arms: Ermine, three bows bent and stringed, paleways in fess gules.

As more and more knights, and their sons, were granted the right to bear arms, so the insignia became by necessity more complex. However, by circa 1500 the original purposes for which heraldry had been introduced (on shields, surcoats, horse trappers and banners, to distinguish combatants in war and in tournaments, and on seals as marks of identity instead of signatures) were becoming obsolete. After the turn of the century the insignia began to be more and more complex, assuming naturalistic forms rather than the traditional symbolic ones. When this occurred, by about 1550, the era of true heraldry had ended and thereafter the science declined: seals were no longer so important because of the spread of literacy, and identification was now achieved on the battlefield by the use of flags, and in the tournament by the use of crests.