MEDIEVAL CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

Jon Cannon

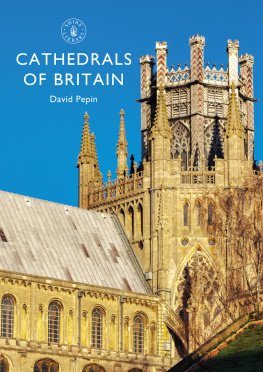

Fotheringhay church, Northamptonshire, built in the Perpendicular style in 1434 for Richard, Duke of York.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

C HURCHES WERE the most ambitious buildings in the medieval landscape. Their designers aimed to provide an appropriate architectural setting for a sacred and theatrical liturgy and a glimpse of what heaven might be like. In pursuit of these goals a restless search took place for new architectural effects. As a result, the architectural motifs they used constantly evolved. These details tend to develop in broad phases known as styles, each with its own distinctive overall aesthetic quality. Knowledge of these styles can be extremely rewarding, enabling one to better appreciate these beautiful works of architectural art; to give an approximate date to entire buildings and parts of buildings; and to understand them better as monuments to the changing times and tastes of the distant past.

The aim of this book is to enable beginners to recognise these styles as they appear in England. To this end, I pick out in particular those details that are most foolproof and easy to remember, and that can thus be described as diagnostic when identifying a given style, while paying less attention to those that are harder to distinguish from each other. Learn these, and you are halfway there. The most straightforwardly diagnostic elements are often ornamental: the way foliage is carved, for example, or the patterns of tracery seen in windows. Other features, such as the shapes of arches and the stone patterns made in roof vaults, are also helpful for diagnosis; the mouldings with which all these things are articulated can, by contrast, be challenging for the beginner, and only the more straightforwardly diagnostic developments are addressed here. Indeed, some very simple mouldings are possible at any period. Definitions of technical terms, picked out in bold when they are first used in the text, will be found in the glossary where they are not self-explanatory.

These stylistic phases were first identified in 1817 by Thomas Rickman, and the names he gave them for the Gothic era, Early English (EE), Decorated (Dec) and Perpendicular (Perp) remain widely used. However, the masons who created these buildings were living in the present moment, as we do, simply attempting to create the most up-to-date and impressive buildings they could. They would not have recognised our stylistic categories, which depend on over five hundred years of hindsight. So a final and subsidiary aim of this book is to give the reader a sense of how these styles evolved in the present.

Two Norman windows at Berkswell, West Midlands, mark this church out as twelfth-century Norman; in the fourteenth century, a window in the Decorated style was inserted into the same wall. Such collisions of style and date give old churches a distinctive character and charm.

I also attempt to describe the overall feel of a style, for the process of identification has a subjective dimension. Apparently subtle changes of detail can have a marked influence on the stylistic effect of a building, and the way in which motifs are used the context of other forms with which they sit can be as diagnostic as the naming of individual motifs in isolation. One needs to develop a sense of the flavour of a style.

TIME AND DATE

It is a myth that it took centuries to build a medieval church. A small parish church took only a few years to build and usually went up in a single campaign, whereas a cathedral could be constructed in forty to sixty years. But progress might be halted in mid-build if funds ran out or wider events intervened. The longer such interruptions lasted, the more likely they were to have a visible impact on the design of the building.

Individual parts of any church might be rebuilt, or new parts added, however, and, when this happened, the style then current was usually followed. Windows (as well as tombs and other fittings) might be inserted into ancient walls, making a structure appear younger than it really is.

As a result, an old church might have developed over a long time, reaching its current form in a complex process that is intellectually stimulating to unravel. Ultimately this story can be fully understood only by studying any surviving documentary evidence and by bringing to bear a type of structural analysis known as buildings archaeology. This seeks to identify disjunctures in the fabric of a building, such as blocked arches or signs of one wall having been joined to another, and to study them to see whether they can be interpreted stratigraphically, that is, whether one part can be proved to be older than another. No matter how persuasive the stylistic or documentary evidence, the story it tells is likely to be flawed if it is contradicted by the stratigraphy of the structure itself. This important subject is beyond the scope of this book, but a list of further reading can be found at the end.

The dates given for the architectural styles in this book should be treated as rules of thumb. Ten years variance either side should be allowed for any date given as a circa (c.), for example, and one should be aware that an individual building may not fit the stylistic categories straightforwardly. In general, however, large ambitious buildings great churches, see below, ).

In spite of this, the system outlined in these pages works surprisingly well. The science of dendrochronology is supplying us with accurate dates for ancient timbers used in smaller or undocumented buildings, and tends to confirm the accuracy of the broad stylistic phases that have been recognised for almost two hundred years.

CHURCH PLANS

It is essential to understand the plan of a church early in the process of exploring it. Though it rarely provides diagnostic dating information in its own right (for exceptions, see pages ), a churchs plan helps orientate the viewer and reveals much about a buildings development.

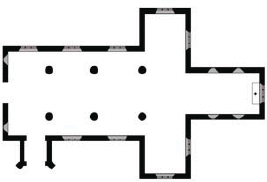

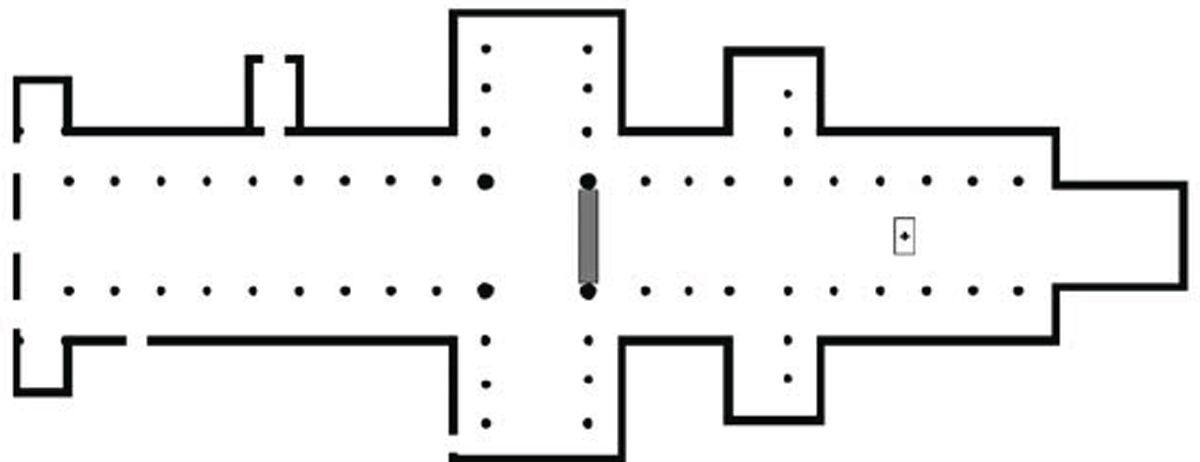

This parish church plan combines cruciform and basilican elements. Only the high altar is shown, but in the medieval period there would have been many more: a chapel in each transept, an altar in front of the screen which divided nave from chancel, and often others, too. The narrow windows in the chancel, the element sticking out to the right, suggest that it is the oldest part of this church. In this church, the tower might have risen over the centre of the building.

Almost all church buildings in England are axial, that is, they are longer than they are broad. The long axis runs east, towards the high altar, which is the buildings raison dtre. The arm of the church that contains this altar is thus called the east end, though its constituent parts have various names. Other parts are named accordingly: north and south transepts, north and south aisles, west front.