THE ART OF

Japanese Architec-ture

HISTORY | CULTURE | DESIGN

DAVID AND MICHIKO YOUNG

Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Text 2019 David and Michiko Young

Illlustrations Tan Hong Yew

Revised and expanded edition of

Introduction to Japanese Architecture

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4629-0657-4

(previously published under ISBN 978-4-8053-1302-2)

Distributed by

North America, Latin America & Europe

Tuttle Publishing

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 U.S.A.

Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930

Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing

Yaekari Building 3rd Floor

5-4-12 Osaki

Shinagawa-ku

Tokyo 141-0032

Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171

Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755

www.tuttle.co.jp

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte Ltd

3 Kallang Sector #04-01

Singapore 349278

Tel: (65) 6741 2178

Fax: (65) 6741 2179

www.periplus.com

21 20 19 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in Hong Kong 1811EP

TUTTLE PUBLISHING is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

FRONT ENDPAPERS Himeji Castle.

PAGE 1 Sensji Temple.

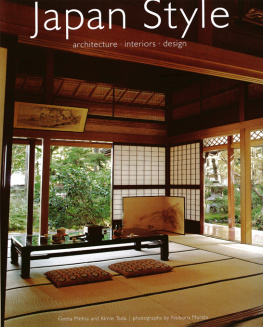

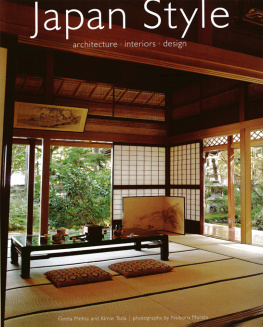

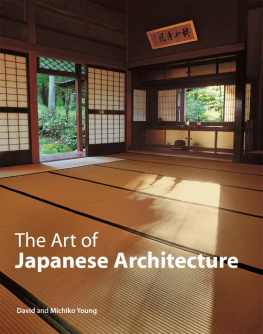

PAGE 2 Interior decor in the 70-year-old home of tea aficionado Sat Teiz, Osaka.

RIGHT Kiyomizu Temple.

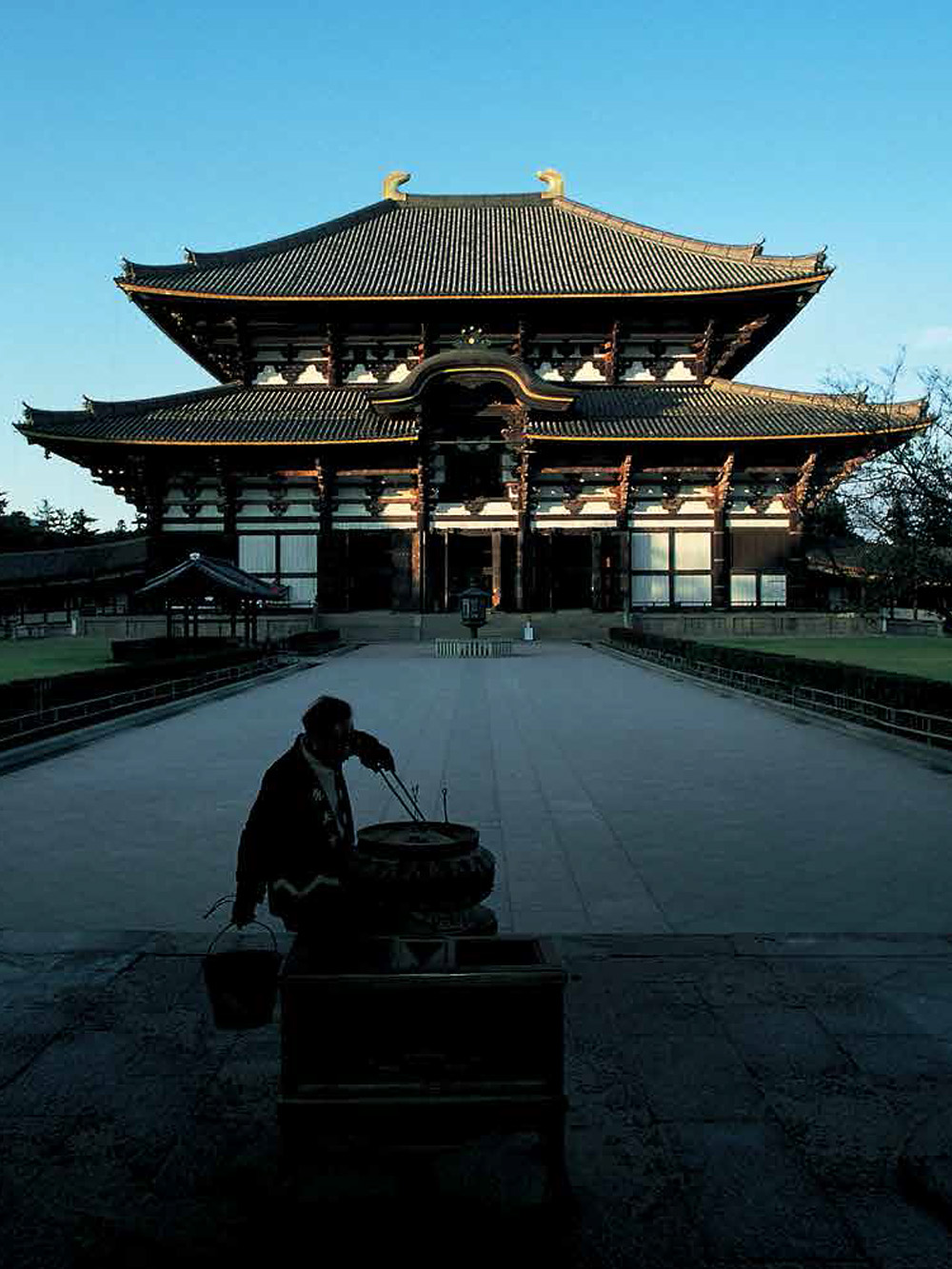

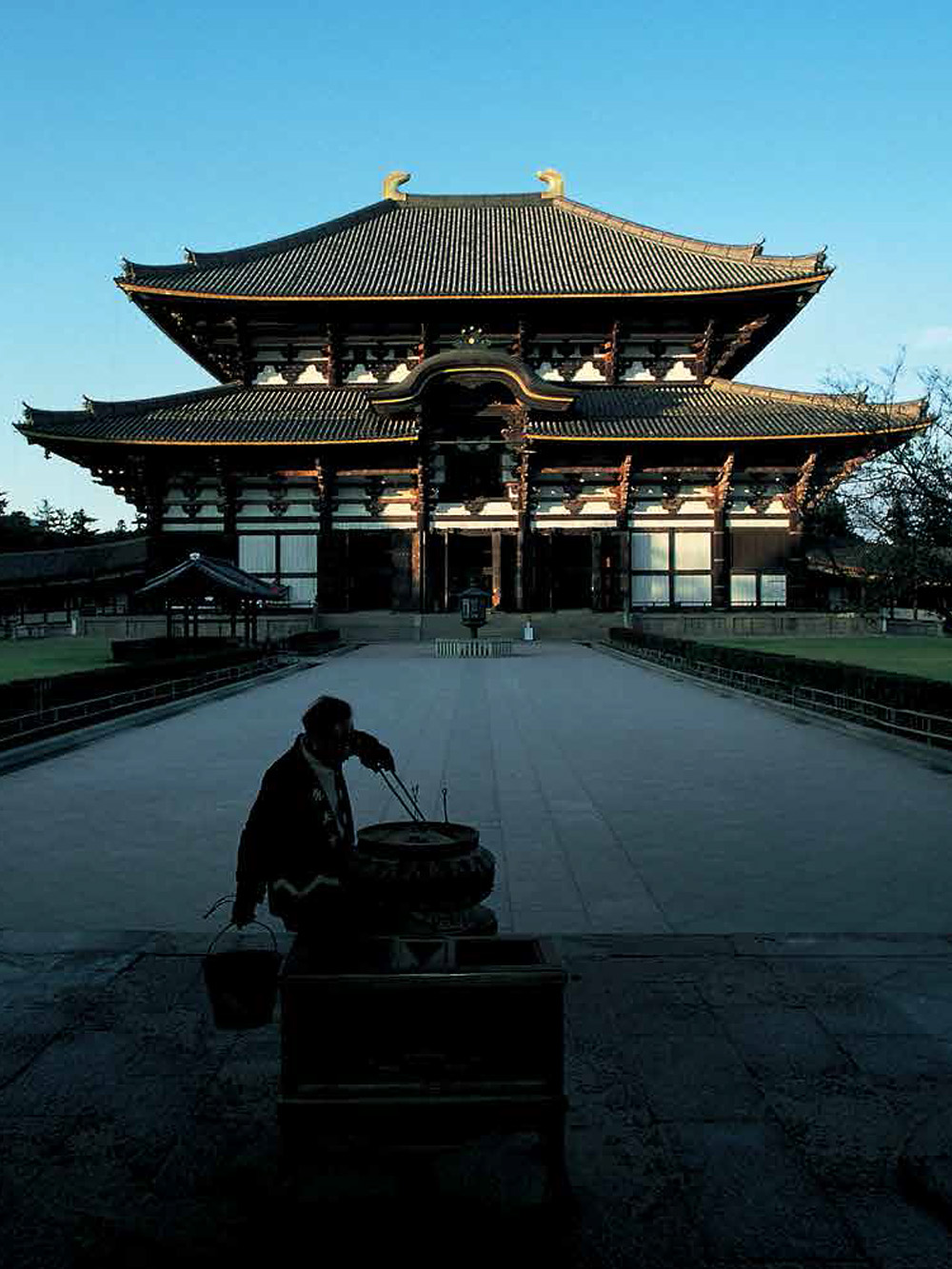

PAGE 6 Great Hall of Tdaiji Temple.

Japanese Architecture: An Overview

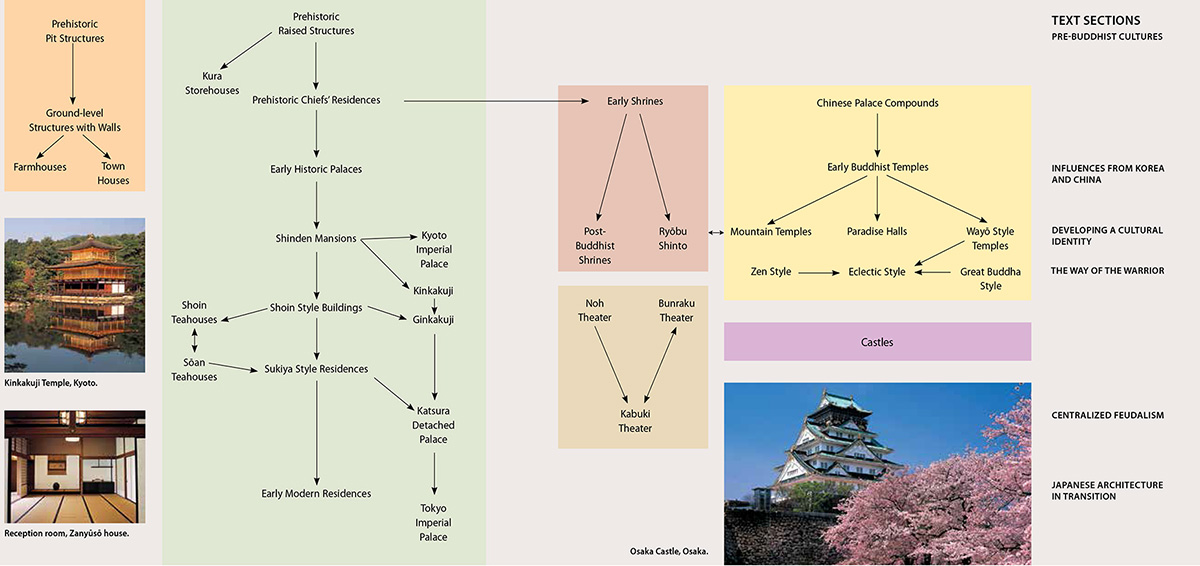

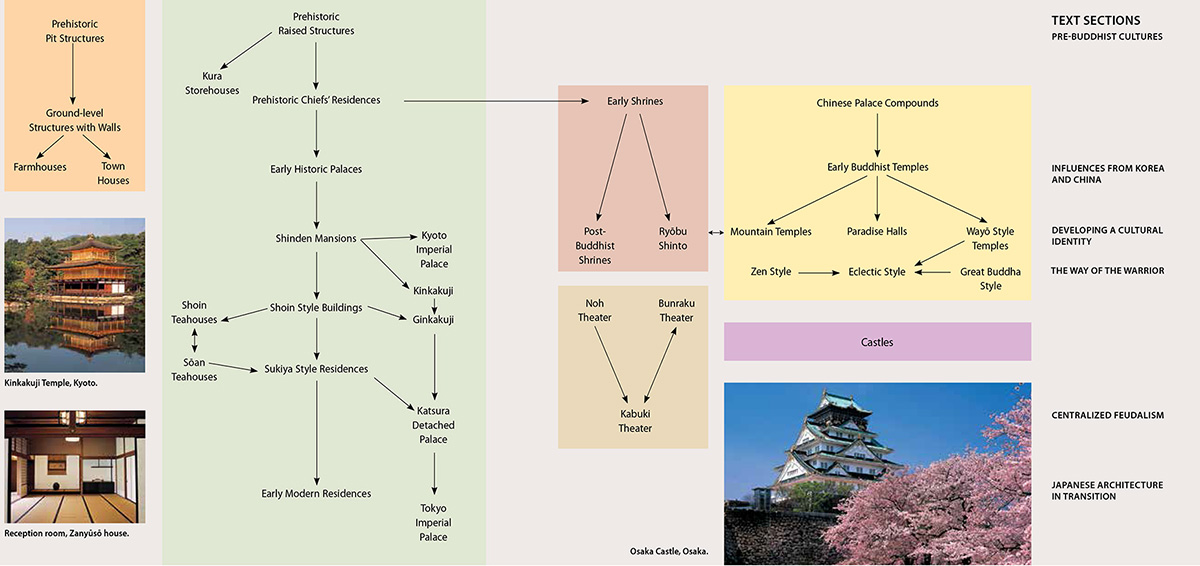

Japanese traditional architecture can be organized into several major genealogical groups on the basis of historical origins and stylistic influences. The most important group is composed primarily of palace, residential, and teahouse styles originating in prehistoric raised structures. Other major groups are commoner residences that evolved from prehistoric pit structures, Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, theaters, and castles. The diagram below has been simplified to emphasize major trends.

Yasaka Shrine, Kyoto.

Jruriji Temple, Nara.

HISTORICAL PERIODS

JMON

10000300 BCE

YAYOI

300 BCE300 CE

TOMB MOUND

300710 (OVERLAPS WITH LATER PERIODS)

ASUKA

538645

HAKUH

645710

NARA

710794

HEIAN

7941185

KAMAKURA

11851333

MUROMACHI

13331573

MOMOYAMA

15731600

EDO

16001868

MEIJI

18681912

Basic Principles

Many architectural styles have developed over the course of Japans long history. Nevertheless, there are several basic principles that can be found in the interesting but complex story told in the following pages. Some of these basic principles describe how core values have influenced the choice of building materials, techniques, and designs. Other principles emphasize cultural processes such as the relation between restraint and exuberance and a passion for preserving the past.

Natural Materials and Settings

Traditional Japanese architecture is characterized by a preference for natural materials, in particular wood. Since wood can breathe, it is suitable for the Japanese climate. Wood absorbs humidity in the wet months and releases moisture when the air is dry. With proper care and periodic repairs, traditional post-and-beam structures can last as long as 1,000 years. Other natural building materials are reeds, bark, and clay used for roofing, and stones used for supporting pillars, surfacing building plat-forms, and holding down board roofs, with an emphasis upon straight lines, asymmetry, simplicity of design, and understatement, exemplified by pre-Buddhist Shinto shrines, farmhouses, teahouses, and tasteful contemporary interiors.

There is also a distinct preference for natural settings. After Buddhism was introduced to Japan from the continent, it was not long before the symmetry of Chinese temple compounds gave way to mountain temples with an asymmetrical layout.

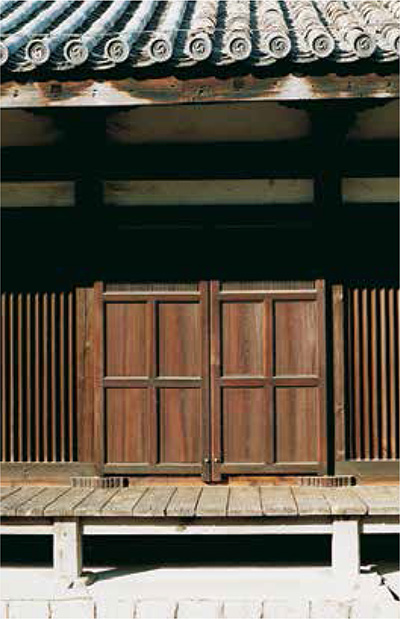

The wood carving on the bottom of the door, as well as the metalwork which graces an adjacent pillar, both part of a gate at Higashi Honganji Temple in Kyoto, illustrate the attention to detail that is typical of many traditional buildings.

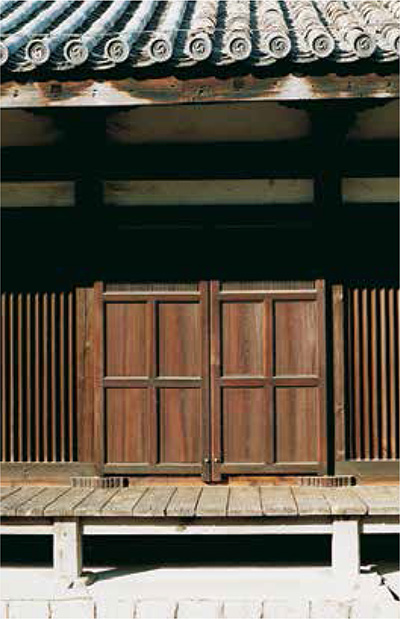

The Japanese love of wood is illustrated in the Zenshitsu Hall at Gangji Temple in Nara City.

Restraint and Exuberance

There is, however, another side to Japanese culture that is not as well knownthe appreciation of exuberant colors and complexity of form in contrast to the restrained tradition with its simplicity and asymmetry. This is exemplified by Chinese style shrines and temples and the mausoleums at Nikk. Such buildings are characterized by a strong contrast between vermilion posts and white plastered walls, elaborate decorations, curved lines, symmetry, and the imposition of order upon nature. Both the restrained and exuberant traditions are favored at different times and places, depending upon the occasion. For example, ceremonial buildings are designed to impress and thus tend to be more exuberant than residential architecture, where the goal is to provide a tasteful and relaxed atmosphere for the occupants.

Attention to Detail

Regardless of whether circumstances call for restraint or exuberance, Japanese architects, builders, artists, and crafts-people pay a great deal of attention to detail. Even when the overall effect of a building is simple, particularly when it is viewed from a distance, a close-up inspection of the building often reveals numerous details that add interest. Attention to detail applies to both technological and design features. For example, at the technological level, the intricate joinery of a traditional building allowed it to be assembled without nails and to be disassembled periodically for repairs. At the design level, the interlocking eave supports of a Buddhist temple can be quite complicated. The basic pattern of the brackets, however, is repeated over and over again to create a visual rhythm that is well integrated and unified.

Next page