Ceremonial gate to the 1894 Sat country house, Oomagari City, Akita Prefecture.

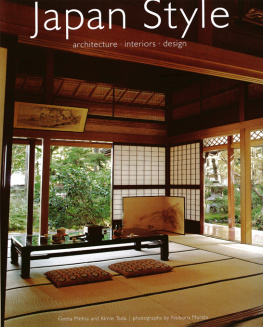

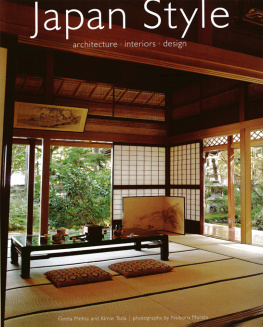

Interior dcor in the 70-year-old home of tea aficionado Sat Teiz , Osaka.

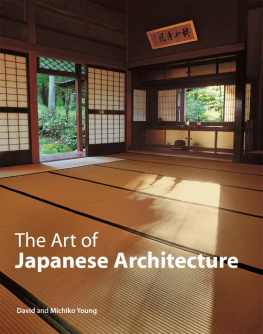

The Art of

Japanese Architecture

David and Michiko Young

Photography by

David and Michiko Young

Ben Simmons

Keyphotos

Murata Noboru

Illustrations by

Tan Hong Yew

TUTTLE PUBLISHING

Tokyo Rutland,Vermont Singapore

Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd., with editorial offices at 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon, Vermont 05759 U.S.A, and 61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12, Singapore 534167.

Text copyright 2007 David and Michiko Young Illustrations copyright 2007 Tan Hong Yew Revised and expanded edition of Introduction to Japanese Architecture (Periplus Editions, 2004)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number 2006929874

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0657-4 (ebook)

Printed in Singapore

Distributed by:

North America, Latin America and Europe

Tuttle Publishing, 364 Innovation Drive,

North Clarendon, Vermont 05759, USA.

Tel: (802) 773 8930; Fax: (802) 773 6993

E-mail: info@tuttlepublishing.com

http://www.tuttlepublishing.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing, Yaekari Building, 3F,

5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032.

Tel: (813) 5437 0171; Fax: (813) 5437 0755

Email: tuttle-sales@gol.com

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte Ltd, 61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12,

Singapore 534167.

Tel: (65) 6280 1330; Fax: (65) 6280 6290

E-mail: inquiries@periplus.com.sg

http://www.periplus.com

09 08 07

6 5 4 3 2 1

TUTTLE PUBLISHING is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

Front endpaper: Teahouse and Zen garden at Jomy ji Temple, Kamakura.

Back endpaper: Tokyo from Roppongi Hills Tower.

Interior of Ry anji Temple.

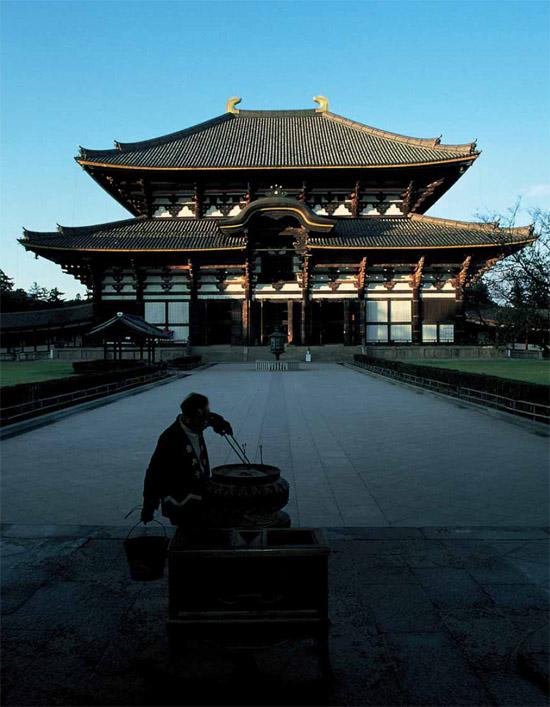

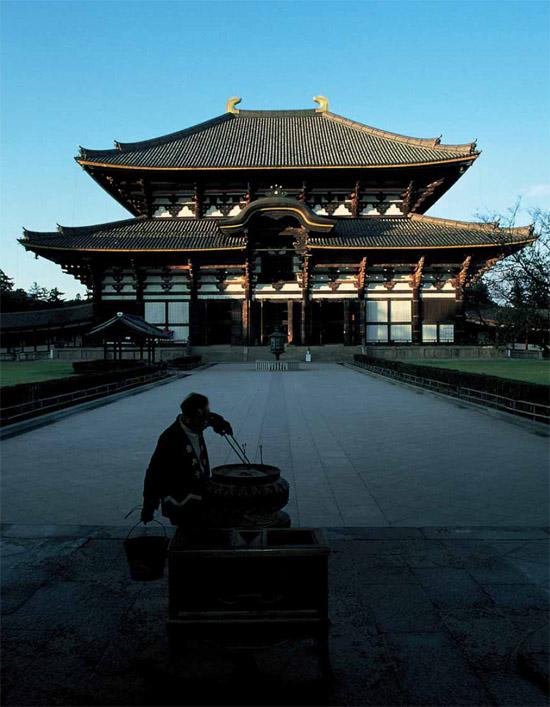

Great Hall of T daiji Temple (page 40).

Contents

Eiheiji Temple in autumn (page 97).

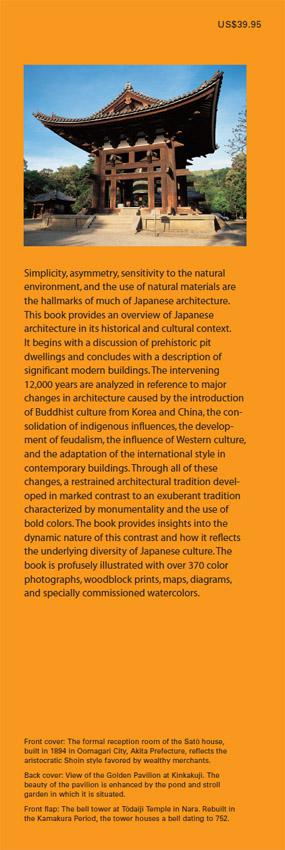

Traditional Japanese Architecture: An Overview

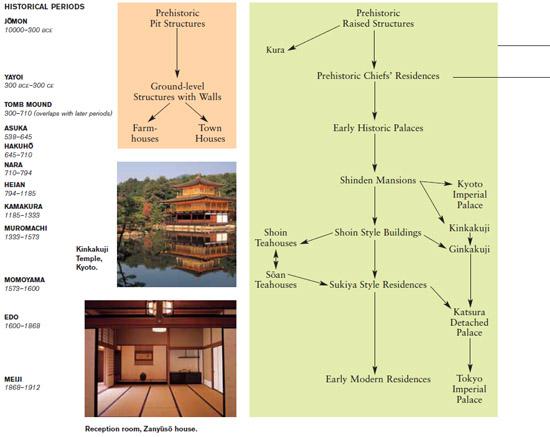

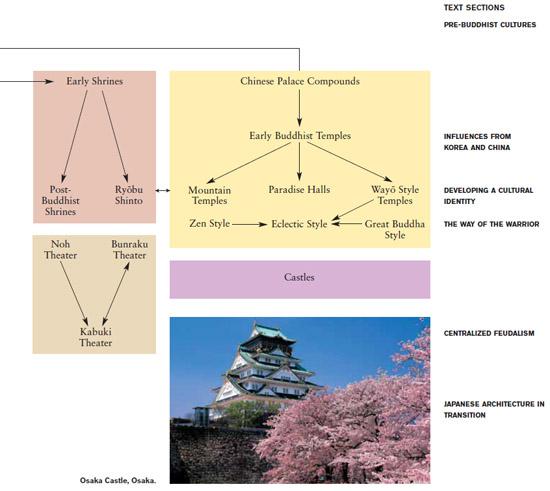

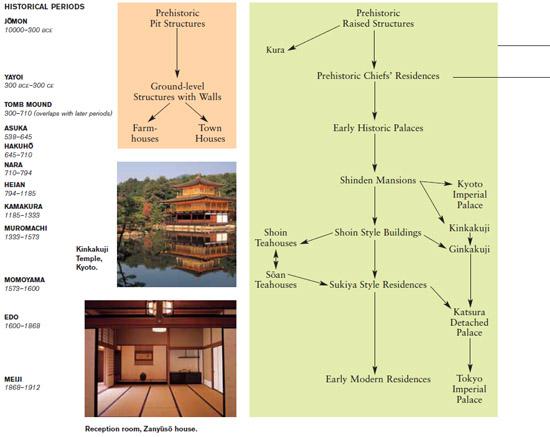

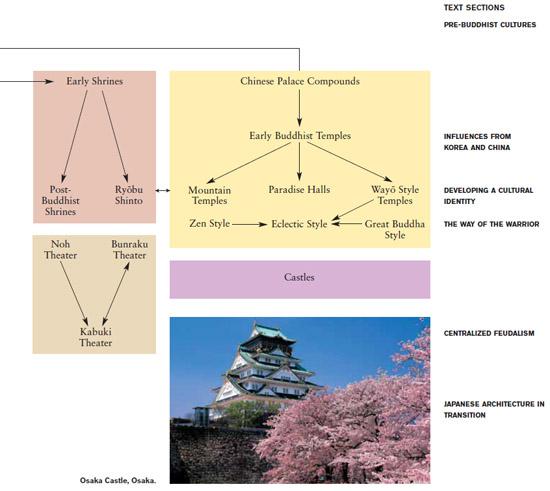

Japanese traditional architecture can be organized into several major genealogical groups on the basis of historical origins and stylistic influences. The most important group is composed primarily of palace, residential, and teahouse styles originating in prehistoric raised structures. Other major groups are commoner residences that evolved from prehistoric pit structures, Buddhist temples, Shinto shrines, theaters, and castles. The diagram below has been simplified to emphasize major trends.

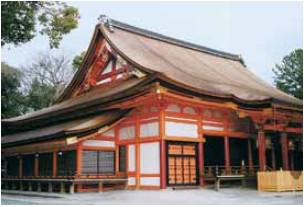

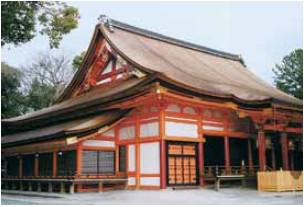

Yasaka Shrine, Kyoto.

J ruriji Temple, Nara.

Basic Principles

Many architectural styles have developed over the course of Japans long history. Nevertheless, there are several basic principles that can be found in the interesting but complex story told in the following pages. Some of these basic principles describe how core values have influenced the choice of building materials, techniques, and designs. Other principles emphasize cultural processes such as the relation between restraint and exuberance and a passion for preserving the past.

The Japanese love of wood is illustrated in the Zenshitsu Hall at Gang ji Temple in Nara City.

Natural Materials and Settings

Traditional Japanese architecture is characterized by a preference for natural materials, in particular wood. Since wood can breathe, it is suitable for the Japanese climate. Wood absorbs humidity in the wet months and releases moisture when the air is dry. With proper care and periodic repairs, traditional post-and-beam structures can last as long as 1,000 years. Other natural building materials are reeds, bark, and clay used for roofing, and stones used for supporting pillars, surfacing building platforms, and holding down board roofs, with an emphasis upon straight lines, asymmetry, simplicity of design, and understatement, exemplified by pre-Buddhist Shinto shrines, farmhouses, teahouses, and tasteful contemporary interiors.

There is also a distinct preference for natural settings. After Buddhism was introduced to Japan from the continent, it was not long before the symmetry of Chinese temple compounds gave way to mountain temples with an asymmetrical layout.

Restraint and Exuberance

There is, however, another side to Japanese culture that is not as well known the appreciation of exuberant colors and complexity of form in contrast to the restrained tradition with its simplicity and asymmetry. This is exemplified by Chinese style shrines and temples and the mausoleums at Nikk. Such buildings are characterized by a strong contrast between vermilion posts and white plastered walls, elaborate decorations, curved lines, symmetry, and the imposition of order upon nature. Both the restrained and exuberant traditions are favored at different times and places, depending upon the occasion. For example, ceremonial buildings are designed to impress and thus tend to be more exuberant than residential architecture, where the goal is to provide a tasteful and relaxed atmosphere for the occupants.

Next page