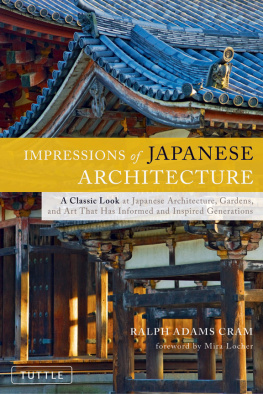

CHAPTER ONE

The Early Architecture Of Japan

JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE is undoubtedly less well known and less appreciated than the architecture of any other civilized nation. Not only this, but it is almost universally misjudged, and while we have by degrees come to know and admire the pictorial and industrial arts of Japan, her architecture, which is the root and vehicle of all other modes of art, is passed over with a casual reference to its fantastic quality or a patronizing tribute to the excellence of some of its carved decoration.

Unjust and superficial as is this attitude it is perhaps excusable, for the architecture of Japan being logical, historical, ethnic, is, of course, profoundly Oriental, and it is as difficult for the Western mind to think in terms of the East, as it is for the same mind to understand or appreciate the vast and splendid fabrics of Oriental thought and Oriental civilization.

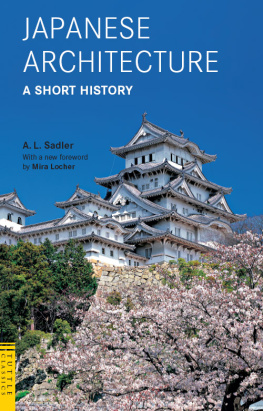

In nearly every instance those who have written most intelligently of Japan and of her art have shown no rudimentary appreciation of her architecture: it is dismissed with a sentence. To the Western traveler it seems only fanciful and frail, a thing unworthy of study; the shrines of Nikko are assumed to be the highest point attained, and the consummate work of the great period between the seventh and twelfth centuries is ignored. Nikko, Shiba, Ueno, indeed only the temple architecture of the Tokugawa period is considered at all, while Horiuji, Yakushiji and the Ho-o-do of Byodo-in, are completely ignored, and the castle and domestic architecture are treated as non-existent.

This is unjust and absurd: it is as though one presumed to judge the architecture of Italy by the works of the High Renaissance, or that of France by the Flamboyant period; the architecture of the Tokugawa Shogunate has many elements of unique grandeur, while its splendor of color and decoration are without parallel, but it is no more to be compared with that of the Nara, Kyoto, and Kamakura periods than is the work of Palladio with the temples of Athens.

As a matter of fact the architecture of Japan is one of the most perfect examples of steady development and ultimate decaythe whole lasting through twelve centuriesthat is anywhere to be found. In the West a certain style lasts at most three centuries, when it is superseded by another of quite different nature, itself doomed to ultimate extinction: in Japan we see the advent of a style coincident with the civilization of which it was the artistic manifestation, and then for twelve hundred years we can watch it develop, little by little, adapting itself always with the most perfect aptitude to the varying phases of a great and wonderful civilization, finally becoming extinct (let us hope only temporarily) after a blaze of superficial glory that led to the imperiling of national civilization and the submergence of a great and unique nation in the flood of Western mediocrity.

Such a progress as this cannot fail to be interesting to the student of art, while the architecture itself, when once it is known, becomes a thing of extreme beauty, dignity, and nobility, immensely significant, profoundly indicative of the fundamental laws that underlie all great architecture.

Carefully analyzed and faithfully studied, Japanese architecture is seen to be one of the great styles of the world. In no respect is it lacking in those qualities which have made Greek, Medieval, and Early Renaissance architecture immortal: as these differ among themselves, so does the architecture of Japan differ from them, yet with them it remains logical, ethnic, perfect in development.

In one respect it is unique: it is a style developed from the exigencies of wooden construction, and here it stands alone as the most perfect mode in wood the world has known. As such it must be judged, and not from the narrow canons of the West that presuppose masonry as the only building material. Again, it is the architecture of Buddhism, and it must be read in the light of this mystic and wonderful system. Finally, it is the art of the Orient, taking form and nature from Eastern civilization, vitalized by the Soul of the East, the artistic manifestation of the religion of meditation, of spiritual enlightenment, of release from illusion. It is separated from the art of the Western religion of action, of elaborate ethical systems, of practicality, by the diameter of being.

Bearing these things in mind, let us consider historically and critically the beginnings and subsequent development of Japanese architecture.

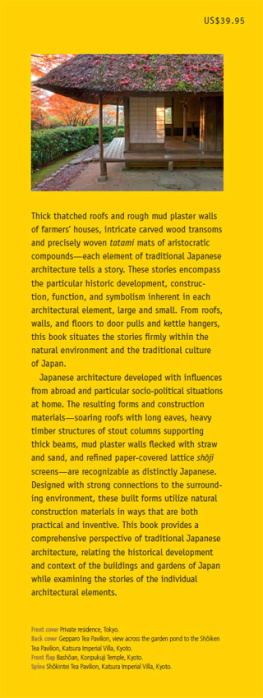

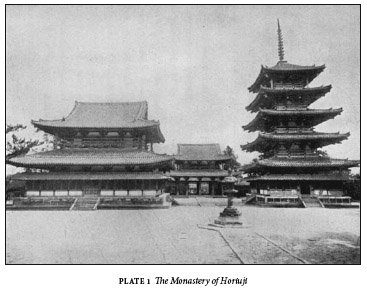

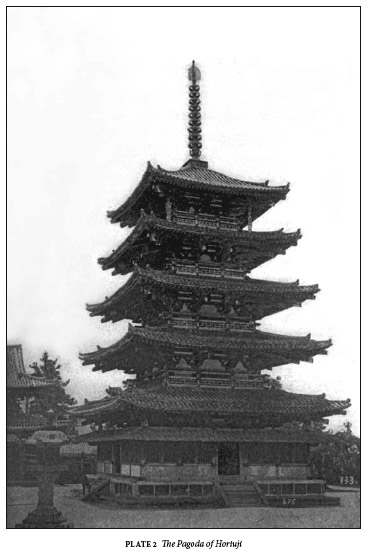

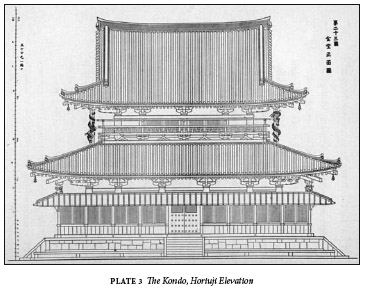

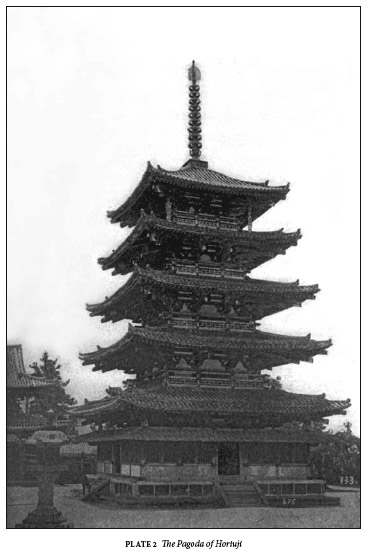

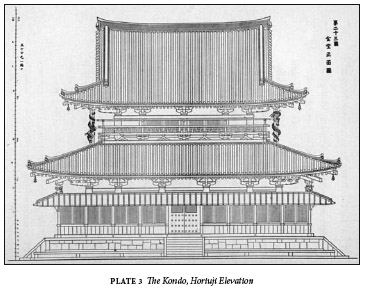

Previous to the reign of the Empress Suiko in the latter part of the sixth century, Japan was a comparatively barbarous State, but the mixture of Tartar and Malay blood had resulted in a race that was waiting only for the impulse that should start it on its career of greatness. The ethnic religion was a primitive cult of the dead of which the modern Shinto is a somewhat artificial restoration. It was impotent of the highest spiritual good, and when the revelation of Buddhism burst on the people of Japan, an entire race rose suddenly into splendid action. Buddhist priests and monks came from Korea to the waiting nation, and with them, at the instigation of Prince Shotoku, came architects, sculptors, and scholars. Nara became the capital: in a few years the monastery of Horiuji was built by Korean architects, and of this first great work of art on Japanese soil, the Kondo, Go-ju-to, and Azekunomon still stand, priceless records of the birth of a great nation. (PLATE 1)

In style they are purely Korean, or rather Chinese, of the Tang dynasty, for the civilization of Korea was that of Chinese Buddhism, and it is doubtful if any material change had taken place in its acquired architecture, though a distinct refinement was visible in the great school of Korean sculpture that was now to make possible in Japan plastic art of the most notable and supreme type.

This Korean or Chinese architecture was, at the time of its advent in Japan, a style that was almost perfectly developed; in simplicity and directness of construction, in subtlety and rhythm of line, in dignity of massing, in perfection of proportion and in gravity and solemnity of composition, it shows all the evidences of a supreme civilization; as must indeed have been the case, for at this time, the last quarter of the sixth century, China was, without doubt, the most perfectly developed and most nobly civilized of the then existing nations of the earth.

This group of buildingsgate, temple, and pagodais the most precious architectural monument in Japan, indeed in all Asia, for it not only marks the birth of Japan as a civilized power, but from it we can reconstruct the architecture of China, now swept out of existence and only a memory. And its artistic value is no less; small as they are, these buildings are almost unequaled in Japan for absolute beauty, and they have remained the type from which all the architecture of the nation has developed.

The Azeku-no-mon, or Middle Gate, remains as it was first built: the lower galleries of the Kondo and Go-ju-to (PLATES 2 and 3) date only from the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries and grievously injure the proportions of the ancient buildings, while the angle supports of the upper roof of the Kondo are of the Tokugawa period, and are also unfortunate. In spite of these additions the extraordinary grace and refinement of the work compel the most profound admiration; and at first it seems as though there were nothing more for Japan to do in the line of development, so perfect seems this architecture borrowed from China and Korea: yet further development was possible as we shall see later.