BOOKS CONSULTED

Chashitsu Teien Gach. Okamoto Teikichi. Tokyo, Isseisha. 1917.

Tetch Chawa. Sasaki Sammi. Kyto, Chad Geppsha. 1928.

Matsudaira Fumai-den. Takahashi Tatsuo. Tokyo, Keibund. 1917. Kwanko Dzusetsu. Ninagawa Noritane. Tokyo. 1877.

Kuroda Josui-den. Count Kaneko Kentar. Tokyo, Hakubunkan. 1917.

Riky Hyaku Shu Shikai. Kanazawa Si. Kyto, Chad Geppsha. 1927.

Chad. Takahashi Tatsuo. Tokyo, Oka Sansho-ten. 1929.

Taish Kshin Chad-ki. Takahashi Yoshio. Tokyo, Sbunsha. 1922.

Chashitsu to Chatei Zukai. Matsumoto Buntar. Tokyo, Kenchiku Shoin. 1920.

Chad Hokan. Kurokawa Shind. Tokyo, Chysha. 1917.

Chad Ykan. Tamaki Issei. Osaka, Maeda Bunshind. 1916.

Chad Kgi. Tanaka Tei.

Kwad to Chad. Nakazawa Risui. Tokyo, Nishod. 1918.

Cha-no-yu Taizen. Korika Kysai. Tokyo, Hakubunkwan. 1901.

Cha-no-yu no Tebiki. Kho-an Ysai, preface by Prince Sanj. Osaka, Nagura Shobunkwan. 1929.

Chashitsu to Chatei. Yasuoka Katsuya. Tokyo, Suzuki Shoten. 1928.

Cha-no-yu Shiori. Nippon Kasei Kenky Kwai. Osaka Sbund. 1928.

Chawa Bidan. Kumata Sjir. Tokyo, Jitsugy no Nihonsha. 1921.

Cha-no-yu. Dokush Shinan. Izawa Kamakichi. Osaka Sanzosha.. 1896.

Cha-no-yu Michi Shirube. Sen Ennsai Sshitsu. Osaka, Maeda Bunshind. 1927.

Shinsen Teisakuden. Osaka Shbund. Reprint. 1894.

Nihon Toki Zensho. nishi Ringor. Tokyo, Shosand. 1918.

Namb Roku. Namb Skei. 1744. Reprint by Kyto Kaiekid 1920.

Ketsu. Edited by the Ketsu Society, revised by Dr. Miura Shgo. Kyto, Sund. 1921.

Kinsei Nihon Kokuminshi. Tokutomi Iichir. Tokyo, Minysha. 1922.

Tokugawa Jikki. Zokkokushi Taikei. Tokyo, Sheisha. 1902.

Nihon Kokumin Taikan. Article Cha-no-yu. Tokyo, Chugai Shoin. 1912.

Bungaku ni arawaretara waga kokumin shis no kenky. Tsuda Skichi. Tokyo, Rakuyd. 1917.

Ris no Kaoku. Mihashi Shir. Tokyo, kura Shoten. 1913.

Kwansei Enkaku Ryakushi. Tokyo Daigaku. Tokyo. 1900.

Eisai Zenji. Kinomiya Yasuhiko. Tokyo, Sheisha. 1916.

Kji Ruien. Yugibu. Tokyo, Tsukiji Kappan Seiz. 1908.

Nihon Kenchiku Jidai Yshiki. Masuyama Shimpei. Kyto, Heiand. 1921.

In English may be consulted:

All About Tea, William Ukers

The Awakening of Japan, Muraoka Hiroshi

The Book of Tea. Okakura Kakuz.

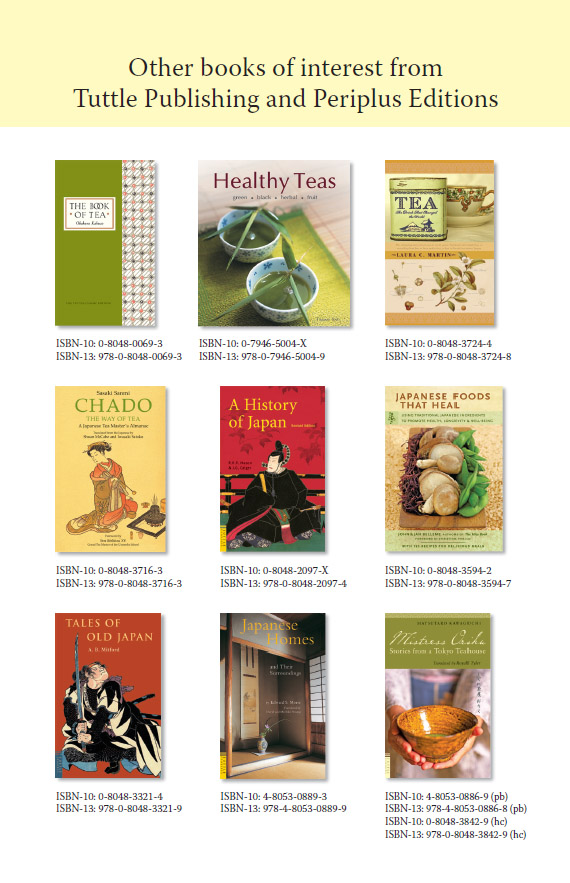

Chad: The Way of Tea, Sasaki Sanmi, translated by Iwasaki Satoko and Shaun McCabe

Cha-no-yu. Japan Society Transactions. Vol. V. Harding Smith.

Cha-no-yu. Y. Fukukita.

Chinese Art of Tea, John Blofield

Chinese Paintings in American Collections (Introduction), Osvald Siren

Code of the Samurai, Thomas Cleary

The Empire of Tea, Iris MacFarlane and Alan MacFarlane

Gardens of Japan. Jir Harada.

Gardens of Japan. J. Conder.

The Great Tea Venture, J.M. Scott

History of Japan. Vol. 3. Appendix. On the Tea plant. E. Kaempfer.

History of Japan, R. H. P. Mason and J. G. Caiger

History of Korean Art. A. Eckardt.

Ikebana, Shozo Sato

In Ghostly Japan, Lafcadio Hearn

Isabella Gardner at Fenway Court, H.D. Carter

Japanese Homes and their Surroundings. E.S. Morse.

Japanese Traits and Foreign Influences. Chapter, On Teaism. I. Nitobe.

Japan and China. Vol. 2 Refinements and Pastimes. Cha-no-yu. Vol. 3 do. Incense ceremony. F. Brinkley.

Life of Hideyoshi. Appendix Note 2. W. Dening.

Pottey of Cha-no-yu. Japan Society Transactions. Vol. VI. C. Holme.

Soul of the Samurai, Thomas Cleary

Tea and Taste, Tania M. Buckrell Pos Senkakusha Okakura Tenshin, Kiyomi Rokuro

The Social History of Tea, Jane Pettigrew

Tea Ceremony, Shozo Sato

Tea: The Drink That Changed The World, Laura C. Martin

Ten Foot Square Hut and Tales of the Heike, A.L. Sadler

Wabi Sabi, Andrew Juniper

Zen Buddhism. D. T. Suzuki.

Zen Flesh Zen Bones, Paul Reps and Nyogen Sensaki

THE EARLY USE OF TEA

It is recorded that in the era of the Three Kingdom in China (221-265 A.D.) Wei Yao of Wu used Tea instead of liquor at entertainments, and that Wang Meng of Tsin also offered it to his guests. In the days of Hsuan Tsung of Tang (713) lived Luh Wuh who wrote the Cha King, which contains all the lore of Tea vessels, Tea making, quality of water, and methods of infusing in vogue in his day, for which he himself was perhaps largely responsible. Evidently Tea was a fashionable amusement of the Tangs as well as liquor, for this was the great era of the tipsy poets. It became more so still under the Sungs when the custom of drinking Powder Tea came in.

In Japan Shmu Tenn (724-749) was the first to offer Tea ceremonially, for it is written that he entertained a hundred priests with it after they had chanted the Sutras for him in the palace. Hiki-cha is the expression used here, and it is uncertain whether it was imported or not.

From the era Enryaku (782) to that of Knin (810) Tea is mentioned in the Anthologies of Chinese poems called Shin-sh and Ryun-sh, and again in those of the period Ninna (885) to Engi (901). Sugawara Michizane also refers to it in one of his poems. In the second year of Engi (903) when the Emperor Uda retired the Emperor Daigo visited him at Ninnaji and was offered Tea. In the Manysh appears the expression Usucha-no-setchie. It seems evident that from these days right through the Kamakura period Tea was a luxury for the Court and Nobility and was not in use among the ordinary people. And it was not made in the way afterwards practiced. There is mention of Japanese tea of Ureshino, a special kind called Kanime-gata or Crabs eye shape evidently of the brick tea variety used by the Sungs, which seems to have been the sort made by Eisai Zenji from the shrubs that he planted at Seburiyama.

Eisai also sent some seeds to Myei Shnin, Abbot of Toga-no-o in Yamashiro in a jar called Kogaki or Little Persimmon, and this jar is now one of the great treasures of that temple. The seeds he planted at Fukase at Toga-no-o and afterwards some of the plants that came up were transferred to Uji, where the soil was found to be extremely suitable. So more and more tea came to be planted there and the methods of treating the leaves by steaming and roasting were studied and improved, with the result that the Tea of Uji is the finest in the country.

Tradition has it that the seed was first sown in the footprints of a horse that was ridden between the old plants in the garden, and it is for this reason that one of the oldest gardens of Uji, that belonging to Matsui of Kobata, is called Koma-no-Ashikage or Colts Hoof Print.

After this, tea was planted at Ninnaji and Daigo, at Takarao in Yamato, at Tanabe in Kii, at Hattori in Iga, at Kawai in Ise, at Hongo in Totomi, at Kiyomi in Suruga, and at Kawagoe in Musashi.

Uji also received attention from the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who ordered his minister uchi Yoshihiro to have plantations of tea made there, and the five gardens of Asahi, Kambayashi, Kygoku, Yamana, and Umoji, which were then established, are still in existence. Then the Governors and Jit of all provinces were ordered to plant tea in their domains, and it was probably at this time that they discovered the existence of the Japanese wild tea.

Tea is plucked about the fifth month, and as some is early and some later it is distinguished as First, Second, and Third crop. The early plucked leaf is called Cha