Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Anna Sherman and Nina Sheth Nanavaty who helped with the editing; Kazue Shibuya for helping with the photoshoots; Kinya Sawada, Hitoshi lmai, Yoshifumi Takeda for showing us some splendid houses; Koshi Baba for introducing Murata and Tada to each other; Masakazu Fujii for the advice on graphic design; Mikiko Morozumi for helping with the translation; Kasumi Yamamoto Stewart for his words of wisdom; lkuyo Toyonaga, Akiko Yamazaki and Yoichi Tada, who has been a great encouragement. Last but not least. we'd like to say thank you to all the architects, the homeowners and their families for their assistance and co-operation.

Noboru Murata

Kimie Tada

Geeta Mehta

Bibliography

Addis, Stephen, How to Look at Japanese Art. New York: Harry N Abrams Inc., 1996.

Akira Naito and Takeshi Nishikawa, Katsura-A Princely Retreat. Tokyo, London and New York: Kodansha International, 1984.

Black, Alexandra and Noboru Murata, The Japanese House: Architecture and Interiors. Boston, Vermont and Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2000.

Bring, Mitchell and Wayembergh, Josse, Japanese Gardens: Design and Meaning. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Elisseeff, Danielle and Elisseeff, Vadime, Art of Japan, New York: Harry N Abrams, Inc., 1985.

Friedman, Mildred and Abrams, Harry, Tokyo Form and Spirit. New York: Walker Art Publishers Center, Harry N Abrams Inc., 1986.

The Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art (all volumes). Chicago: Art Media Resources.

Heino, Engel, Measure and Construction of the Japanese House. Boston, Vermont and Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1989.

lenaga Saburo, Japanese Art: A Cultural Appreciation. Tokyo: John Weatherhill Inc., 1979.

lwatate, Marcia and Conran, Terence, Eat. Work. Shop.: New Japanese Design. Singapore, Hong Kong and Indonesia: Periplus Editions, 2004.

Kakudo, Yoshiko, The Art of Japan. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1991.

Katoh, Amy Sylvester and Shin Kimura, Japan Country Living: Spirit. Tradition, Style. Boston, Vermont and Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2002.

Kidder, Edward Jr, The Art of Japan. London: Century Publications, 1985.

Mahoney, Jean; Peggy landers, Rao, At Home with Japanese Design: Accents, Structure, and Spirit. Boston, Vermont and Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2001.

Mason, Penelope, History of Japanese Art. New Jersey: Prentice Hall/Harry N Abrams Inc., 1993.

Morse, Edward S, Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings. Boston, Vermont and Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1989.

Nishi Kazuo and Hozumi Kazuo, What is Japanese Architecture? Translated by H Mack Horton. Tokyo, London and New York: Kodansha International, 1996.

Paine, Robert Treat and Soper, Alexander, The Art and Architecture of Japan. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Smith, Bradley, A History of Japanese Art. Tokyo: John Weatherhilllnc., 1971.

Stanley-Baker, Joan, Japanese Art. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Stewart, David, The Making of Modern Japanese Architecture-1868 to the Present. Tokyo, London and New York: Kodansha International, 1987.

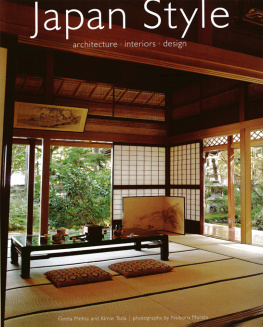

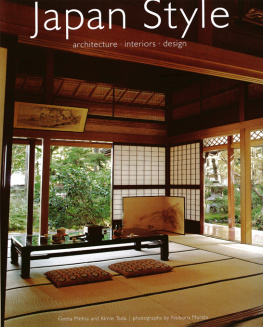

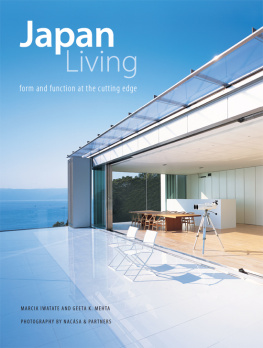

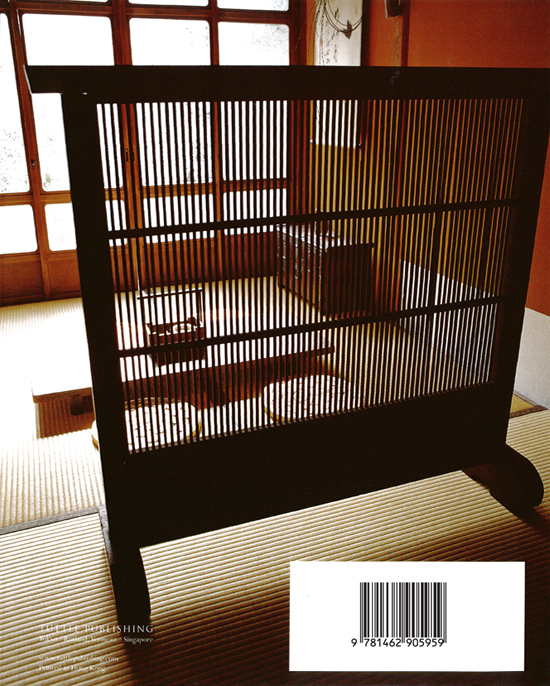

Minimalism and simplicity are the hallmarks of Zen-inspired traditional Japanese interiors. This effect is achieved by a rhythm of vertical and horizontal surfaces paired with natural colors. Exterior wall panels and shoji screens have been removed in this room to let the summer breeze and garden view in, making it "as open as a tent."

What is Japanese about a Japanese House?

A surprising intellectual leap in housing design took place in Japan during the 14th century. This was an idea so powerful that it resonated for the next 600 years, and still retains enough influence in Japan as shown in the houses in this book. This intellectual leap sought to "eliminate the inessential," and seek the beauty in unembellished humble things. It sought spaciousness in deliberately small spaces, and a feeling of eternity in fragile and temporary materials. A house's interior was not to be just protected from nature, but to be integrated with nature in harmony. Influential Zen Buddhist priests in the Muromachi and Momoyama Periods articulated this ideal so well that thought leaders in many fields followed it, and the entire Japanese society aspired to it. What resulted were homes that speak to the soul and seem to hold time still. They provide a quiet simple base from which to deal with the world.

Around the time that European and English homes were becoming crammed with exotic bric-a-brac collected from the newly established colonies, Japanese Zen priests were sweeping away even the furniture from their homes. Out also went any overt decorations. What was left was a simple flexible space that could be used according to the needs of the hour. At night the bedrolls were taken from deep oshire cupboards, and during the day they were replaced, making space for meals, work, play and entertaining. This "lightness" was in part a response to Japan's frequent earthquakes, and in part to the Buddhist teachings about the transient nature of all things. It is interesting to note that this ephemerality is not reflected in the architectural tradition in India, China or Korea, the three countries from where Buddhism arrived in Japan.

Wood is the preferred building material in Japan. The country's Shinto roots have inculcated a deep understanding of and respect for nature. Japanese carpenters have perfected techniques of drawing out the intrinsic beauty of wood. Craftsmen often feel, smell and sometimes even taste wood before purchasing it. Although stone is available in abundance in mountainous Japan, it was traditionally used for the foundations of temples, castles and, to a limited extent, for homes and warehouses. Even brick buildings, when first built in Ginza around 1870, stayed untenanted for a long time, because people preferred to live in well ventilated wooden buildings.

Traditional Japanese builders designed houses from the inside out, the way modern architects professed to do until about two decades ago. A house's exterior evolved from its plan, rather then being forced into pre-conceived symmetrical forms. Bruno Taut, a German architect trained at Bauhaus, and who came to Japan in 1933, claimed that "Japanese architecture has always been modern." The Bauhaus mantras of "form follows function" and "less is more," as well as the "modern" ideas of modular grids, prefabrication and standardization had long been part of Japanese building traditions.

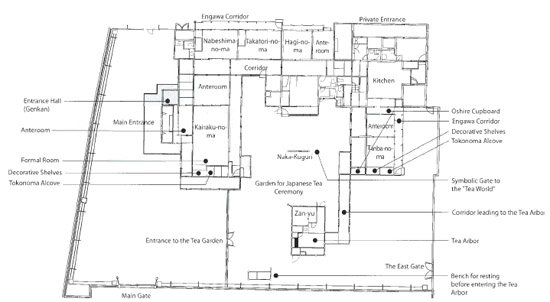

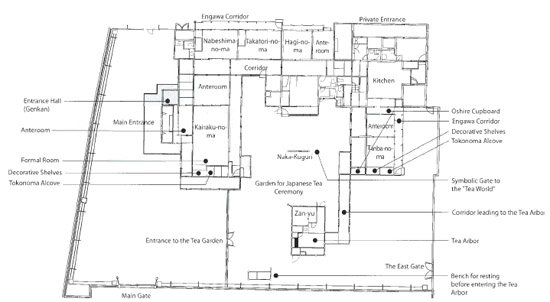

Floor-plan of Zan Yu So the organic organization of a Japanese house

Around the time when Leonardo da Vinci was developing a system of dimensions that scaled the human body for use in architecture, Japanese craftsmen standardized the dimensions of a tatami mat to 90 x I 80 centimeters, which was considered adequate for a Japanese person to sleep on. Every dimension in a Japanese house relates to the module of a tatami mat For example, the height of fusumo doors is usually I 80 centimeters. The width of a structural post is usually one-tenth or one-fifth of 90 centimeters, and the post's bevel is one-seventh or one-tenth of its width. Thus, as in da Vinci's model, the proportions and scale of a traditional Japanese house can be considered to flow from the dimensions of the human body.

The houses shown in this book are a wonderful reminder that there are other alternatives to "big is beautiful," and that eternity is not about permanent materials. Living in the "condensed" world-Japan's population is half the size of the US, but it occupies a land area about 30 times smaller-the Japanese have developed a unique understanding of space. An ikebana arrangement charges the area in and around itself, and that space becomes an integral part of the design. The arrangement would not be nearly as effective without this empty space. One of the most famous buildings in Japan is the Taien tea hut built by Sen no Rikyu, the famous 16th century tea master. This masterpiece of Japanese architecture measures a mere one-and-three-quarters of a tatami mat, or approximately three square meters. This tiny house gives an example of how small houses do not have to take the form of the proverbial "rabbit hutches," but can be beautiful and open like the Kamikozawa home (pages 178-183) and the house owned by Toru Baba and Keiko Asou (pages 98-107). After all, how much space does a man need?