Bibliography

Adachi, Barbara. The Living Treasures of Japan. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1973.

Brandon, Reiko Mochinaga. Country Textiles of Japan. New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1986.

Durston, Diane. Old Kyoto. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1987.

Grilli, Elise. The Art of the Japanese Screen. New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill, Bijutsu-sha, 1987.

Hauge, Victor, and Takako Hauge. Folk Traditions in Japanese Art. New York, Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1973.

Havens, Thomas R.H . Artist and Patron in Postwar Japan. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Hibi, Sadao, ed. Japanese Tradition in Color and Form. Tokyo: Graphic-sha Publication Co., Ltd., 1987.

Hirai, Noriko. Tsutsugaki Textiles of Japan. Kyoto: Shikosha, 1987.

Kawashima, Chuji. Design of Japanese Folk Houses. Tokyo: Sagami Shobo, 1986.

Kawashima, Chuji. Minka: Traditional Houses of Rural Japan. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1986.

Kojima, Setsuko, and Gene A. Crane. A Dictionary of Japanese Culture. Tokyo: Japan Times, 1987.

Koren, Leonard. New Fashion Japan. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1984.

Lee, Sherman . Japanese Decorative Style. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1961.

Lee, Sherman. The Genius of Japanese Design. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1981.

Massy, Patricia. Sketches of Japanese Crafts. Tokyo: Japan Times, 1980.

Minnich, Helen Benton. Japanese Costume. Tokyo and Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1963.

Morse, Edward Sylvester. Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings. Kyoto: Kyoto Shoin Company Ltd., 1988.

Nibe, Harumi. Hyaku no Midori no Naka de. Tokyo: Bunka Shuppan, 1987.

Okakura, Kakuzo. The Book of Tea . Tokyo and Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956.

Salmon, Patricia. Japanese Antiques. Tokyo: Art International Publishers, 1975.

Shirasu, Masako. Hana. Tokyo: Shimmu Shoko, 1989.

Slesin, Suzanne, et. al. Japanese Style. New York: Clarkson N. Potter Inc., 1987.

Statler, Oliver. Japanese Inn. New York: Random House, 1961.

Stern, Harold P. Birds, Beasts, Blossoms, and Bugs: The Nature of Japan. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1976.

Sudo, lsao. Nihon Seikatsu Jibiki. Tokyo: Kobundon, 1989.

Tanaka, lkko, et. al. Japan Design. Tokyo: Libro Port Company, Ltd., 1984.

Tanaka, lkko, et. al. Japanese Coloring. Tokyo: Libro Port Company, Ltd., 1984.

Tanizaki, Junichiro. In Praise of Shadows. Tokyo and Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1984.

Tsubouchi, Fujio. Akari no Kodogu. Tokyo: Kogei Shuppan, 1987.

Watson, William, ed. The Great Japan Exhibition, Art of the Edo Period, 1600-1868. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1981-82.

Yagi, Koji. A Japanese Touch for Your Home. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1982.

Yanagi, Soetsu. Folk Crafts in Japan. Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, 1949.

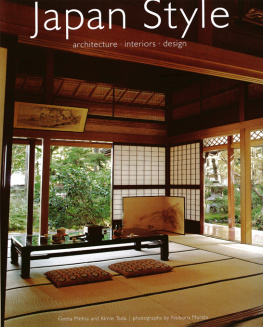

Yoshida, Mitsukuni, et. al. Japan Style. Tokyo, New York, San Francisco: Kodansha International Ltd., 1980.

Light and Space

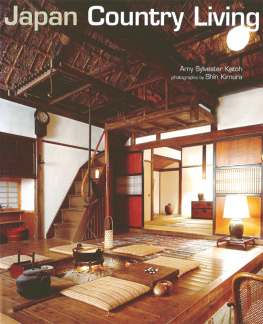

Light and space abound in this restored farmhouse. The high beams are tied with straw rope.

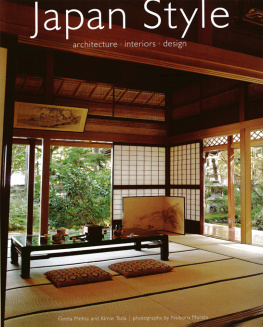

A Japanese room is a composition of line and texture and the play of light therein. Its beauty derives from the effect of its shadows, which suggest light, and its walls, which both delineate and allude to space beyond with windows and other vistas. The silent, the unseen, the unexpressed speaks just as tellingly as the spoken, the visible, the obvious.

The Japanese aesthetic is played in a minor key. The subtle is preferred to the obvious. Light implies the presence of shadows, and it is the shadows that are loved. Unlike Westerners, who worship the sun, the Japanese have moon-viewing parties; they use parasols for protection from the sun.

Traditionally it has been felt that things of beauty are enhanced by shadow and reflection. In In Praise of Shadows, Junichiro Tanizaki observed that even for household implements Japanese prefer "colors compounded of darkness," whereas in the West the preference is for the "colors of sunlight." The colors of darkness appeal because of the underlying beauty to be discovered within. How much more beautiful the gold leaf of screens and scrolls, the lustrous depth of lacquer, the handloomed weave of a silk obi (kimono sash) when seen by flickering candlelight or the gentle light of an andon (paper-covered lamp).

The Japanese approach to light can be seen in the Akari light. Inspired by traditional lanterns covered with washi, lsamu Noguchi, himself the product of an East-West marriage, created his first Akari lights in the 1950s. These were simple washi-and-bamboo lamps designed to capture and diffuse light softly, gently. Well aware of the warmth and beauty of the chochin (traditional wood-and-paper lantern), Noguchi warned against using bright bulbs within.

Some things are better left suggested, undefined, unclear. The Akari light was designed to provide warmth, shadow, and atmosphere, rather than fluorescent clarity. That these beautiful, handmade lights have remained popular for over thirty years, and are found in even the most modern interiors (pp. 14, 15, 23, and 41), attests to the wisdom of the traditional approach to lighting, as well as to Noguchi's sensitive fusion of traditional and modern ideas.

Shji and sudare (reed or bamboo blinds) create a sensuous, textural atmosphere in a roorn. The harsh light of day is refined and diffused. The world outside takes on a surreal quality when filtered through bamboo or paper (pp. 32, 34, and 35). Inside, an ordinary room can be transformed into a magical place by shoji and sudare, which give play to light and shadow.

Shji help define space too. Closed, they create a wall, a barrier, even a room. Opened, the wall or room disappears. Different types of screens can also be used, from the simple tsuitate (free-standing screen) covered with a Clifton Karhu woodblock print in John McGee's formal entrance (p. 39), to the elegant Kana school screen in the Mitsui house (p. 40). Fusuma (sliding doors) also create space, bringing tremendous flexibility to the Japanese interior. Four small rooms circumscribed by fusuma can suddenly become one large room. The marvelous flexibility of space created by shoji and fusuma brings exciting possibilities to modern living, where space is limited. In our own modern apartment, sets of shoji on two walls close to create an instant dining room when we entertain guests.

The concept that space is containable even by paper walls is striking to Westerners, who know walls only as solid barriers. Walls, even paper walls, can be effective in maintaining privacy, creating a mood or an instant room. The magic of shoji! The power of paper walls!

GENKAN: THE FACE OF A HOME

The genkan is the index of the lifestyle inside the home. More than just a beautiful entrance, it is a space for a psychological transition from the public outer world to the private inner world. Visitors are welcomed by a perfect objet d'art, an arrangement of fresh flowers, or a jaunty collection of objects that defines the taste, interests, and style of those who live within.