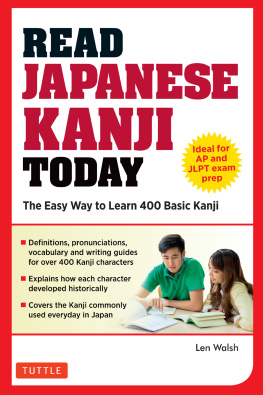

ABOUT TUTTLE

BOOKS TO SPAN THE EAST AND WEST

Our core mission at Tuttle Publishing is to create books which bring people together one page at a time. Tuttle was founded in 1832 in the small New England town of Rutland, Vermont (USA). Our fundamental values remain as strong today as they were thento publish best-in-class books informing the English-speaking world about the countries and peoples of Asia. The world has become a smaller place today and Asias economic, cultural and political influence has expanded, yet the need for meaningful dialogue and information about this diverse region has never been greater. Since 1948, Tuttle has been a leader in publishing books on the cultures, arts, cuisines, languages and literatures of Asia. Our authors and photographers have won numerous awards and Tuttle has published thousands of books on subjects ranging from martial arts to paper crafts. We welcome you to explore the wealth of information available on Asia at www.tuttlepublishing.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to: Eric Oey for all his input. Our editors Cathy Layne and June Chong for shepherding this project through, our designer Sow Yun, and everyone else at Tuttle.

Further thanks to all contributors and interviewees for their thoughtful insight and enthusiasm.

A special thanks to the Yokohama Tattoo Museum, Horiyoshi III, Don Ed Hardy, Doug Hardy, Horiren, Hori Magoshi (aka Hori Shige V), and Crystal Morey for all their advice and assistance. Fostin Cotchen, Jun Takagi and Hiro Hara for their wonderful photos.

A big thanks to the work of Merrily C. Baird, Ian Buruma, Basil Hall Chamberlain, Thomas W. Cutler, Margo DeMello, John Dower, Sandi Fellman, Christine M. E. Guth, Wolfgang Herbert, Tadasu Iizawa, Marisa Kakoulas, Noburo Koyama, Donald McCallum, Saburo Mizoguchi, Cecilia Segawa Seigle, Haruo Shirane, Tattoo Burst, D. M. Thomas, W. R. Van Gulik, and Hiroko Yoda, as well as aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/, hanzismatter.blogspot.jp, onmarkproductions.com, and web-japan.org, among others.

Brian would like to thank his wife and three kids, his parents, his in-laws, everyone at Kotaku and Gawker Media (especially Nick Denton, Stephen Totilo, and Luke Plunkett), Jerry Martinez, and finally, Rolling Thunder Pictures.

Hori Benny would like to thank his family for their unconditional love. He would also like to thank his adopted country, Japan, whose rich irezumi traditions continue to inspire.

CHAPTER 1

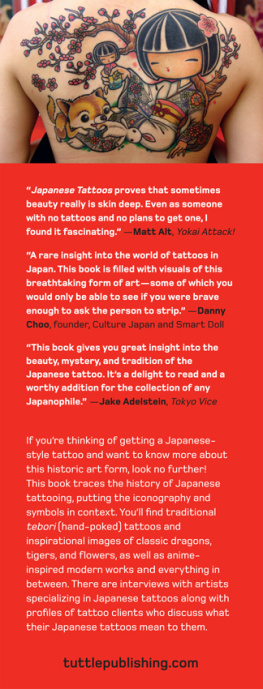

KANJI TATTOOS

WORDS AND PHRASES, PUNISHMENT AND PLEDGES

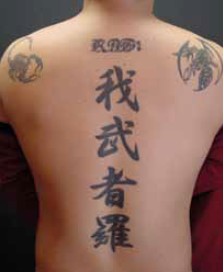

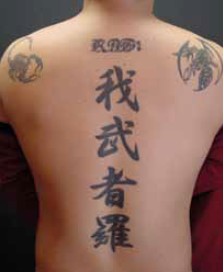

Japanese script has found its way into tattoos in various forms over the centuries. Its easy to see the appeal: Japanese writing is beautiful, with flowing characters and pictograms. Its also easy to see why so many tattooists outside the country often make mistakes when working with Japanese script: the language is complex, and incorporates several different writing systems.

In recent years, bad kanji tattoos have become a clich. Just look online: Theres the man who thought he got the word courage tattooed on his back, but found out the characters ( taika ) actually meant big mistake. Theres the woman who ended up with ( shuu ), thinking it meant friendship, only to find out it means ugly, or the individual sporting a tragic ( baka gaijin , meaning stupid foreigner) tattoo. Then there are the folks who end up with ink that either doesnt make sense, or worse, is complete gibberish. This is enough to put anyone off the idea of getting a kanji tattoo! It shouldnt, though, as long as you make an informed decision. In Japan, irezumi arent done on a whim; there is traditionally more thought given. Japan has a long history of script tattoossome of it good, some of it bad, and all of it fascinating.

Old Chinese and Japanese manuscripts, a mix of fact and folklore, do mention tattooing. One Chinese account dating from the late third century states that in Japan, decorative markings denoted rank or social status, and that Japanese shell divers had tattoos to protect themselves from harmful sea creatures. But by the fifth century, tattooing had an entirely different meaning: punishment and shame. Punitive tattoos were likely imported to Japan via China and were used to ostracize. In ancient China, which influenced early Japanese culture, tattoos were used to mark criminals and slaves, so its certainly possible that this is how disciplinary tattoos came to Japan. The Nihon Shoki ( Chronicles of Japan ), which dates from 720 AD and is the countrys second-oldest history text, recounts how in 400 AD Emperor Richu had a rebel tattooed on the face for attempting to plot a coup, showing just how damning tattoos were. The same text recounts a story of an old codger with a tattooed face who commits theft, with the obvious implication that tattoos marked crooks. Yet another story tells how in 467 AD Emperor Yuryaku had a man permanently inked on the face after his dog killed an imperial bird. Irezumi werent exactly winning in the ancient history PR department.

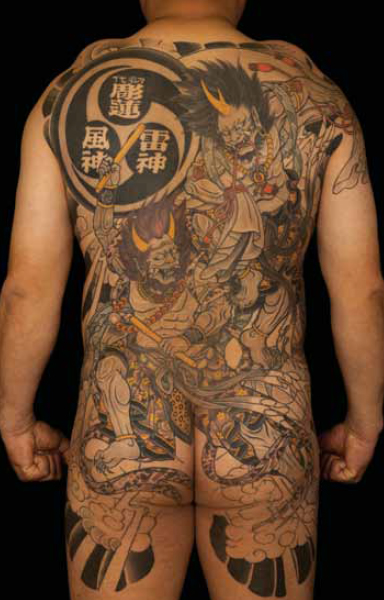

Common locations for kanji irezumi include the chest and the spine. The tattoo ( fushakushinmyou ) is sometimes translated as not sparing ones life for a worthy cause, but actually, its a religious expression that refers to self-sacrificing dedication to Buddha or Buddhist law. The tattoo ( gamushara ) means daredevil, hothead, or even lunatic. Yikes!

This motif depicts Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, the legendary Japanese sword used to slay the Japanese dragon Yamata no Orochi. Traditionally, this dragon is said to have eight heads, but here it has one. A bonji character alluding to the Buddhist deity Fudo Myoo (see page ) is emblazoned on the blade.

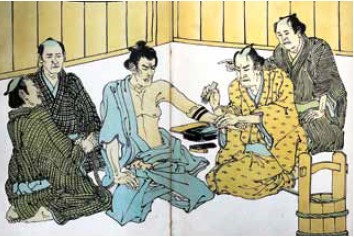

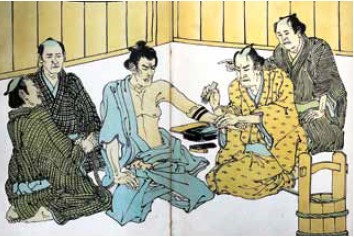

During the seventh century, irezumi began to fade as punishment, and save for one surviving mention of punitive tattoos in a 13th-century legal code, it wasnt until the 17th century that penal tattoos were back with a vengeance. In the early 1600s, the Tokugawa shogunate took over Japan, creating a highly stratified society and secluding the vast majority of the country from the outside world. By the later part of that century, irezumi penalties returned, along with the slicing off of noses and earsthe latter a gruesome punishment that was no longer inflicted by 1720. Punitive tattoos, however, stuck around.

The act of applying punishment tattoos is called irezumi-kei ( ), with kei referring to penalty, sentence, or punishment.

Next page