Special thanks are in order to the many people whose advice and support enabled us to write a book about decorating with the Japanese obi. At Tuttle, our editor provided the initial enthusiasm for the project and then proceeded to implement and refine our vision. Our Australian photographer, Vincent Long, worked tirelessly in the U.S. and Tokyo to give us the shots that we needed. Thanks also to Michael Barrett and Michael Guttuso for providing us with additional photographs and styling. In Tokyo, Barbara Knode introduced us to the design genius of Shoji Osugi and we spent a delightful day together photo-graphing his exquisite obi creations. Naomi Iwasaki Hoff graciously provided us with her original obi pillows and teaboxes for use in the book. A big thank you goes to Martha Widman for her fine sewing skills; Martha has relined or repaired hundreds of obi for us over the years and her handiwork is featured in many of the obi pillow designs shown in this book. We also appreciate the hours that Noriko Faust spent translating the tiny kanji (Chinese characters) on the back of obi for us. In Washington D.C., the staff at the Textile Museum was invaluable in contributing to our research. Additional information was obtained by consulting with the many obi experts in Japan who patiently answered our endless questions. We especially want to thank Gallery Kawano and Toshiko Yamazaki, Shigeko Ikeda, Seizaburo Ando at Odawara Shoten, Yukiko Matsuzaki, Yoshiko Chida, Ryoko Masakane, Naiko Funakoshi, Aiko Sasaki, Setsuko Miura, and the Nishijin-ori Kai in Kyoto. And to those friends who so generously opened their homes to us for photographing the obi in all manner of settings, a very special thank you!

In the U.S.

Connie and Steve Lanzl, Loralie and Lee Parks, Sarah and Phil Nelson, Joanne and Philip Horton, Susan and Alan Kasper, Gerald Falls, Lee and Dick Nance, Carol O'Donnell Miscio at Celestial Connections, Richard Santos

APPENDIX ONE

History of the Obi

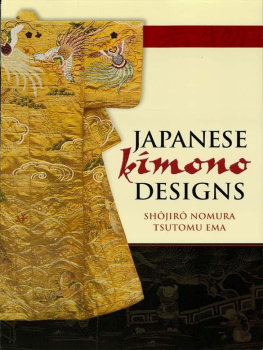

The earliest obi was more functional than ornate. In the Heian period (794-1185), the first obi consisted of a narrow sash used to hold up culotte-like pants called hakama. This undergarment was covered by layers of unlined kimono, so that the obi was not visible.

Later, after the Muromachi period, (1392-1573), women of the samurai class began tying their obi on the outside of their garments, usually knotted in the front or on the side. During this time the uchikake, or long outer coat, became popular, and, although the obi was visible, it was overshadowed by the decorative uchikake.

By the Momoyama period, (1573-1615), the obi was slightly wider and sometimes made of silk, with plaids and checks being popular patterns. An optional obi style consisted of a braided fabric with tassels added to each end. This narrow braided obi was then wrapped around the waist and tied with dangling knots. Largely ornamental, the braided, tasseled obi never really caught on.

Traditional clothing of the Edo period, (1600-1868), included the kimono and obi as we know them today. Then, as now, the obi was necessary to keep the kimono securely closed in front (over other fasteners that hold the garment together). By the middle of the Edo period, obi measurements were standardized to 360 cm by 26.8 cm (142 in. by 11 in.).

Edo fashion was influenced by courtesans and entertainers of the age. Women of the samurai class continued to wear the simpler kosode kimono tied together with an obi made of braided cords. Outside the samurai class women experimented with more elaborate kimono, the furisode style, often seen on the Kabuki stage. Characterized by long, flowing sleeves, the furisode kimono was accented by a large, loosely-tied obi.

For many years all styles of obi were usually tied at the front or on the side, but the back position became the more accepted form by the mid-Edo period. It is said that this rear style originated in the mid-1700s when a Kabuki actor, imitating a young girl, came on stage with his obi tied in the back. Another reason for the change may have been that the sheer bulk of the wider obi became too cumbersome for tying in the front.

Even though the obi was becoming an important part of a woman's ensemble, it was not until the middle of the Edo period that it became as prominent as the kimono. It was then that designers, weavers, and dyers all focused their talents on creating longer wider, and more elaborate obi.

The Meiji era, (1868-1912), witnessed a revolution in the textile industry with the advent of electric weaving looms and chemical dyeing techniques from the West. During this time women's kimono ceased to be worn in the free-flowing style of earlier days. The new fashion was to tuck them at the waist so that the length of the kimono could be adjusted in accordance with a woman's height. These tucks and folds were visible and became part of the art of tying the obi. Obi were sometimes made shorter than before, with the most popular bow being the simple taiko musubi, or drum bow.

As for the men's obi, or otoko obi, the earliest styles were simple and functional, much like the women's. For a short time during the Edo period, men experimented with wider obi made of more exotic fabrics, but this fashion did not last. After expanding to the current width of 10-15 cm (4-6 in.), men's obi became much more subdued in color and design. Even today, you will see very little design on a man's obi, with the exception of a fringe trim or interesting weave.

Note: The hexagonal tortoise-shell motif, used throughout this book, is a popular Japanese design element that symbolizes longevity and good fortune.

APPENDIX TWO

Weaves, Dyes, Stitches

The vast majority of all the obi produced in Japan today come from a district in Kyoto known as Nishijin. This area is filled with hundreds of workshops where weavers labor at their looms, about a fourth of which are still hand-operated. Since the 15th century, Nishijin has been the center of the Japanese textile industry. Initially famous for brocades, twills, and gauzes produced on draw looms, Nishijin switched to Jacquard looms in the late 1800s after a team of its weavers returned from France with the new technique.

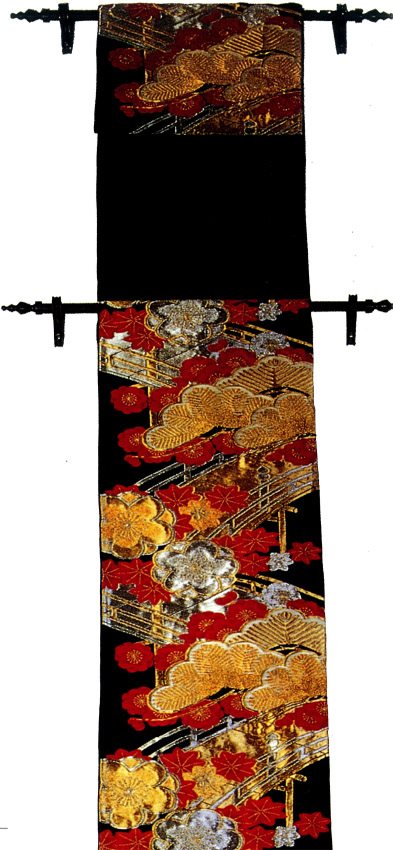

The high-quality brocade obi produced by the Nishijin artisans is known as nishiki, meaning "beautiful color combination." It is characterized by the lavish use of gold and silver threads with patterns of flowers, birds, or ancient geometrical designs. Another style of elaborate obi manufactured in Nishijin is the tsuzure, or tapestry weave. Both brocade and tapestry obi are the most ornate and expensive of all obi.

Lightweight obi are made using an open weave, resulting in a gauze-like material, commonly referred to as karami oh. These are worn mostly in warm weather or with a casual kimono. A distinctive silk weave, also popular in the summer, is the Hakata obi. Named for the area of Kyushu where it originated, Hakata obi are characterized by their series of woven stripes.

Any unlined obi woven in one piece may be referred to as hitoe. This word literally means "one layer" and is also used to describe unlined kimono. Hara-awase is a term used when speaking of a double-sided obi that has a different fabric on the underside, usually black or white. This reversible style enables the wearer to enjoy two different designs with one obi.

![Shinichi Nagatsuka [永塚慎] - Modern Japanese Ikebana: Elegant Flower Arrangements for Your Home](/uploads/posts/book/320284/thumbs/shinichi-nagatsuka-modern-japanese.jpg)