Contents

Guide

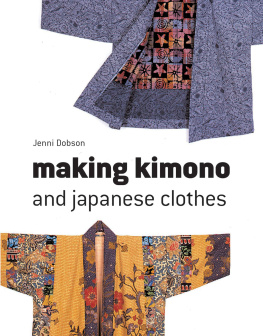

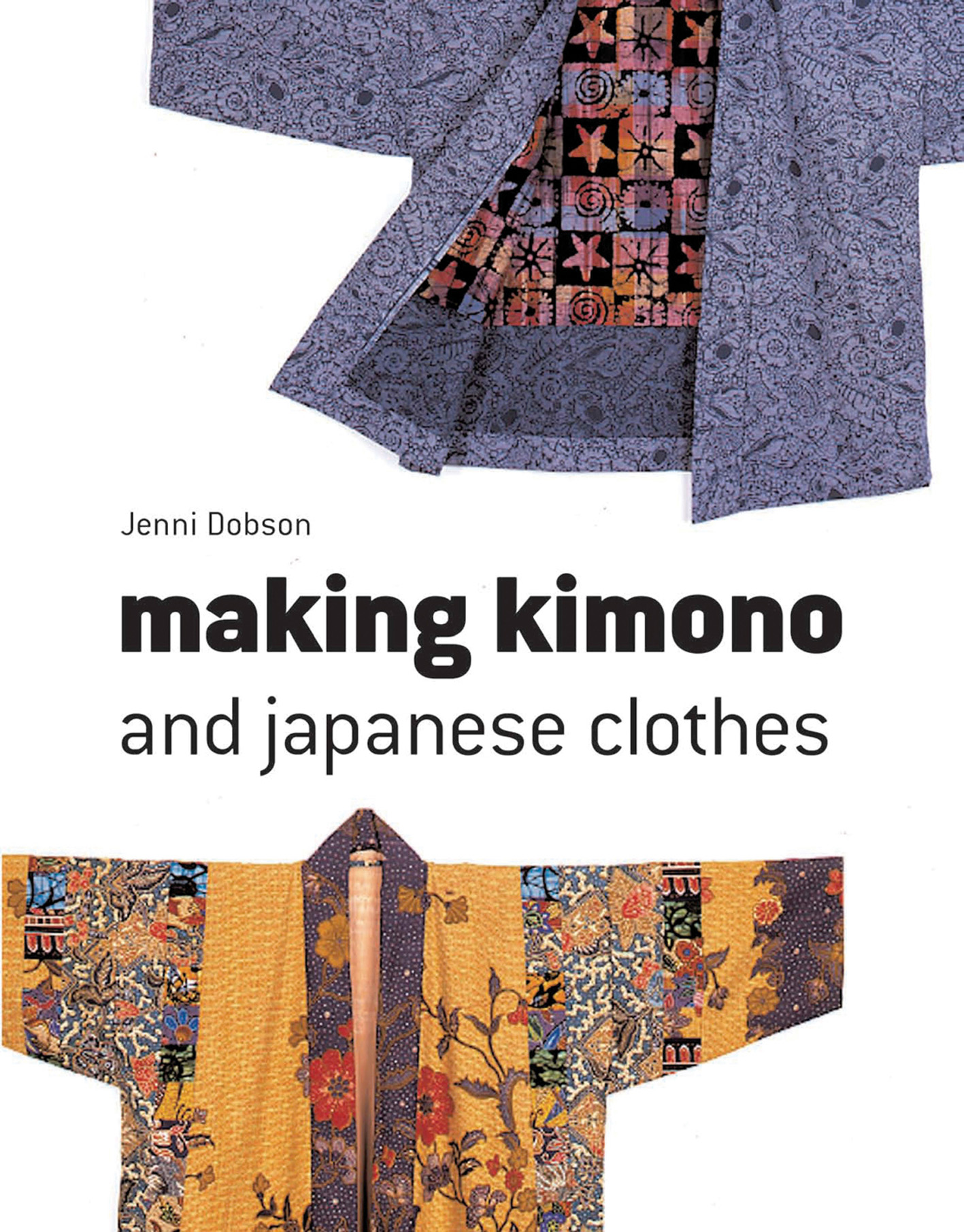

making

kimono

& japanese clothes

making

kimono

& japanese clothes

Jenni Dobson

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Pat Allen. Some of her fabrics and threads, together with her Bernina, helped to make this book possible, even though she did not live to see it. Thank you, Mum!

Authors acknowledgements

Influences on a book such as this obviously come from many directions, some unrecognized because they are so subtle. My longstanding friend and mentor, Jill Liddell, author of The Story of the Kimono, has been the source of much of my background knowledge about Japan over the years and a fountain of encouragement.

I also wish to acknowledge the comprehensive work by John Marshall, Make Your Own Japanese Clothes (Kodansha, 1988), which I purchased in the early 1990s. My book does not presume to copy this work, but rather to offer a simpler level of making and to emphasize the decorative possibilities of Japanese garment forms.

In this aim I was much encouraged and supported by Mary and Shiro Tamakoshi of Euro-Japan Links, London, England, who loaned most of the source garments from which my patterns were derived and who gave generous permission for photography. The lovely light blue haori, source garment in , is a treasured gift from my Japanese friend Atsuko Ohta of Patchwork Quilt Tsushin, Tokyo. I am indebted to friends Sue Barry and Minou Button-de Groote for their garments and Sue in particular for her advice on silk painting. Thanks also to Dianne Huck of the British Patchwork and Quilting magazine for permission to rework an article on shibori, first printed in the magazine, for the benefit of this book.

I must mention Pat Allen, my mother, and Mary Dale, maternal grandmother, for without their skills and knowledge in my childhood days, I would not be the needlewoman that I am. Finally, a big thank you to my husband and family for their support and tolerance of my stitching career!

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A brief history of the kimono

When westerners first arrived in Japan and enquired the name of the clothing, they were told kimono which literally means thing to wear! Kimono was thus a generic word that embraced a whole range of garments, but gradually it has come to refer to the full-length robe, made from straight strips of cloth, that people the world over would recognize. It is a word, like sheep and fish, that has the same form for both singular and plural uses.

Early in Japanese history, people were much influenced by contact with China, wearing Chinese-style robes and adopting the Chinese hierarchy of colours for rulers and court officials. During the Nara period (AD 710794), however, garments resembling the kimono began to appear and, after Japan suspended contact with China (one of several such episodes), a style began to emerge that became uniquely Japanese.

Kimono were generally worn in layers, each carefully cut to reveal a glimpse of colour, the layers being sequenced and coordinated to suit the season. At a time roughly similar to the mediaeval period in Europe, court ladies would wear twelve or more robes at a time, this conspicuous consumption proving that one could afford to sustain the lifestyle of the court. Sleeves also went through a period of being far more enormous than a sleeve actually needs to be. This compares with court fashions in Europe at late mediaeval times, where the same ostentatious display of wealth in costume similarly represented power and authority. Just as in Europe, too, this was a period in which heraldry was highly developed and socially important. Your family crest, or kamon (see ), was displayed on your clothes, your household effects and the livery worn by your household servants.

Embroidery enriches this print with satin stitch and couched gold thread.

A 20th-century recreation of the multi-layered Heian ensemble worn by court ladies of the period.

Eventually the number of layers in an ensemble settled down to about five. However, in the cold of winter one might wear more, and sometimes the relative coldness of winters was described in terms of the number of kimono that had been needed! Despite this, the average kimono was not usually padded, although the silk robes worn at court were usually lined, especially those intended for winter wear (with lining colours also carefully specified to suit the ensemble).

The most familiar form of the kimono is based upon a version called a kosode, which translates as small sleeves. Japanese girls and young women used to wear flowing sleeves, sometimes to floor length, in a style called furisode. Such sleeves were considered to be tools of flirtation because they could be waved about to catch the eyes of young men. Consequently, upon marriage, these sleeves had to be cut off short. A beautiful sample of embroidery, featured on , is actually just such a cut-off sleeve. As women grew older, therefore, their sleeves were worn shorter, and the colours they chose also became more subdued.

If you ever have the chance to study a genuine kimono (in other words, not the sort sold in department stores for tourists), take it. It will be a tremendous opportunity to learn about both textile decoration and the construction of these historic garments. I once received a box of kimono pieces which came indirectly from a Japanese Lady. Inside the box were a number of pieces that clearly came from the same garment and I realized there was perhaps a chance to reassemble the whole. In the event, a few bits were missing. Where the panels had been unpicked, tiny strands of silk sometimes remained, and the distinctive marks of the running stitches that had originally held all together could still be seen. Matching their subtle variations showed whether the correct two seams were being joined.

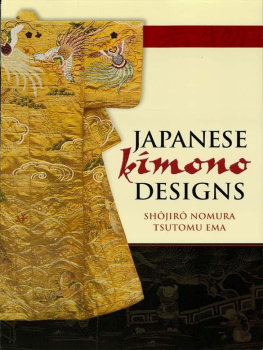

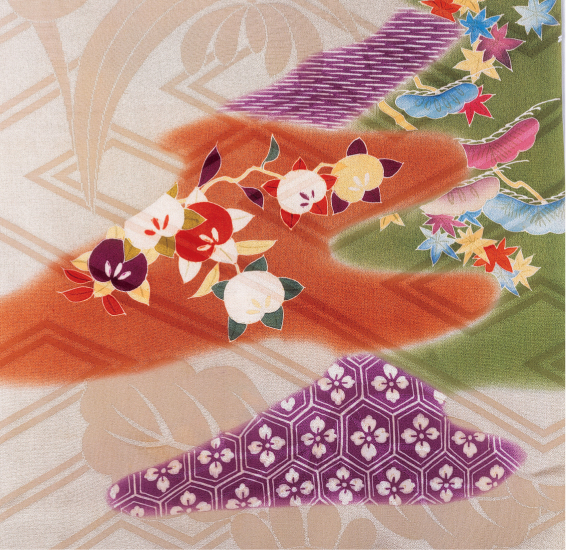

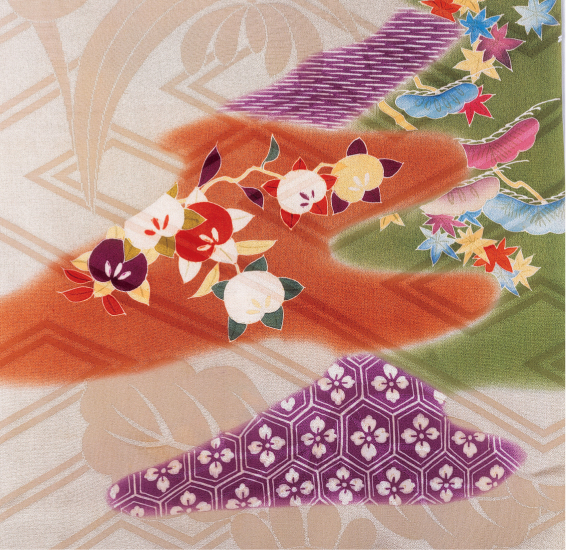

This detail shows several tide-pools of colour with resist-dyed motifs, flowing freely over woven geometric and floral motifs in the background silk.

This Showa-period kimono displays typical decorative features composed in an asymmetrical yet balanced way. Note the scattered embroidered accents: colourful plum blossoms and maple leaves in metallic thread.

On the reverse of the fabric, itself a beautiful putty-coloured silk jacquard, were hand-drawn pencil marks. These marks sketched out the areas to be dyed with various pools of colour. Still visible were the characters specifying the shades: white, for example, or rust or purple. This showed that the garment had been a bespoke piece of dyeing. On the right side, the fabric was decorated with painted or dyed sprays of flowers and so forth, some of which had been embellished further with satin stitch or metallic thread embroidery. This kimono was probably produced by a workshop that offered the skills of many individuals, and it was made using very traditional methods, including assembly by hand, at a time well after the introduction of the sewing machine. The garment may date from early in the Showa period (192689).