The uncritical rush to Westernise is over. During the countrys seemingly unstoppable economic rise, it seemed the obvious, international thing to do. But in the years since many Japanese have taken a more appreciative look at their long and complex artistic and cultural tradition. This is what now inspires many ideas, with interpretations varying from the subtle to the extreme.

Lycra and Wood

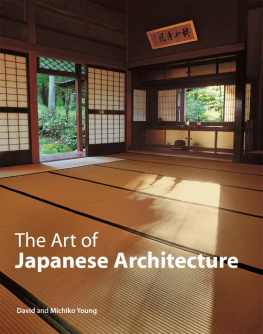

New ideas for tatami rooms

For this house in Yokohama, Ken Yokogawa (who also designed the house featuring the oversized curved window on page 68 and the seaside villa on page 146) combined two traditional characteristics of Japanese living spaces that are in some ways contradictory. One is the high, open space with exposed timbers typical of minka country dwellings, of which the Hattori house on page 36 is a fine example. The other is the low-ceilinged proportion associated with small tatami rooms, which the Japanese have typically found comfortable and appropriate, particularly for sleeping.

He achieved this by locating the sleeping areas on a mezzanine close to the rafters, so that the full height of the building can be appreciated from the ground floor living areas, and by exposing the timber structure. Yokogawa then went an imaginative step further by building two adjoining tatami rooms with a twisteach has a tent-like roof of white lycra, held taut in the middle by a single cord attached to a rafter.

His reasoning was to create a kind, soft ceiling that would allude to a cloud, and break with the notion of tatami rooms as restrictive spaces overloaded with cultural tradition. In this way, individual living areas for guests keep an isolated privacy within a large, open interior and, in Western terms at least, evoke the sense of tree-house cabins.

Evoking something of an old farmhouse, exposed natural timber beams allow a view from the living room the full height of the house. The balcony of the tatami rooms is at the upper right.

The entrance to the house, with its juxtaposition of dark timbers and white walls, is preceded, just inside the door, by a concrete floor that swells up in the middle to make an almost sculptural flat-topped pedestal.

Perched over the main living area, under the exposed rafters of the ceiling, are two adjoining mezzanine tatami rooms. Lycra was chosen as the soft ceiling material because of its two-way stretch properties. It adds a tent-like atmosphere, and for guests who stay here there is a hint of indoor camping.

The view from the bedroom through to the two tatami rooms. Sliding doors can enclose all three rooms.

The architects detailing includes the design of door handles in the form of two interpenetrating spheres, recalling molecular models.

Barrier-free Minimalism

White simplicity in the Tofu House

In a quiet residential area of Kyoto, facing a small park, this single-storey white cube earns its name, the Tofu House, from its minimal faade. Inside, the clean simplicity, even severity, is continued in a bright barrier-free space. The virtually seamless living area was, in fact, part of the specifications for this, the retirement home for an elderly couple. Anticipating the owners reduced mobility in future years, architect Jun Tamaki designed the entire house on one level, with no obstructions.

Although the volume of the house is reasonably modest8 x 14 x 4 metresTamaki gave it what he calls a deliberately monolithic impression, with massive white walls. These are emphasised by the deep recesses of the windows, their frames concealed in the plasterwork. Despite the thickness of the walls, however, no space is actually wasted, as the subsidiary rooms and various storage spaces are embedded in them. The 3.6-metre ceiling rises the full height of the building and adds to the sensation of spaciousness.

To minimise the distances that the couple need to move, the core of the house is a large basic living space that can be partitioned into three when needed. Sliding doors, following the traditional fusuma , are used throughout, running smoothly on high-precision rails. The two main partitions that can divide the area into thirds slide fully back into recesses in the walls, while cross beams above them carry a separate upper set of partitions operated by handles.

Cantilevers above and below make both the roof and the house itself appear to float, giving it an impression of lightness and also of being cubic, hence the name. The single deeply-recessed window on the faade maintains the minimal simplicity.

A deeply sculpted recess in the centre of one wall is a modern version of the display alcove, or tokonoma , while on either side sliding doors access the colour-coded kitchen at left and utility room at right.

A steel girder projects into the bathroom and is intended to carry a sliding invalid support in the event of either of the owners becoming infirm in the future. The doorway would then be widened.

The rear of the house from the recessed alcove, with the sliding panels drawn back. The papered wall at the rear of the house conceals a porthole window to the bathroom.

The view from the front window along the length of the house. The two cross beams, foreground and background, support sliding fusuma panels above and below, so that the space can be completely, or partially, divided into three rooms. The rear, seen here partially closed off, is used for sleeping.

On the side facing the alcove, a much deeper recess facing out over a small garden. This is a relaxation area for taking tea and for playing games such as the go board set up here. Beyond, the two circular tables seen on page 17 have been converted into one large oval table by the addition of a removable central section.