Acknowledgments

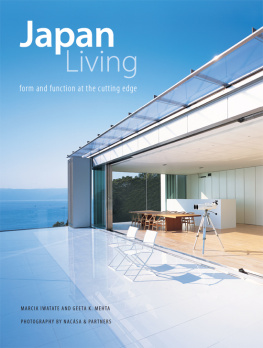

It is with sincere gratitude that I acknowledge a few of the many people who gave freely of their time and knowledge in the making of this book:

Dana Buntrock and Ruri Kawashima for opening doors.

Rainer Becker, Raymond Chan, Laurent Chaudet, Christophe Hazebrouck, Hiromi Imai, Eddie Tan, as well as Yuki Fukasawa of ZOOM! and the staff of Super Potato for generosity and assistance.

Motohisa Arai, Paula Deitz, Joann Gonchar, Zeuler Lima, Noriko Sato, and Noor Azlina Yunus for encouragement and advice.

Saori Yamamoto for unending help and good humor.

Tadao Ando, Kenya Hara, and Kiyoshi Sey Takeyama for energy and insight.

Yoshio Shiratori and Takashi Sugimoto for boundless generosity, wisdom, and friendship.

And Takayuki Murakami for making all things possible.

All photographs have been taken by Yoshio Shiratori of ZOOM! except as noted below.

I would like to thank the following for supplying additional photographs for the book:

Millime for the photographs of Ryurei (page 113) and Komatori (front endpaper and pages 6, 11415) taken by Takashi Hatakeyama, and for the photograph of Hikari taken by Masaki Miyano (page 116).

Mitsumasa Fujitsuka for the photograph of Maruhachi (page 26).

Niki Resort Inc. for the photographs of Niki Club (pages 1268).

Ryohin Keikaku Co. Ltd for the photographs of MUJI Aoyama-sanchome (pages 1047) and The Future and MUJI exhibit (pages 10811).

Shotenkenchiku-Sha Publishing Co. Ltd for the photographs of Caf TOO taken by Shinichi Sato (pages 15661).

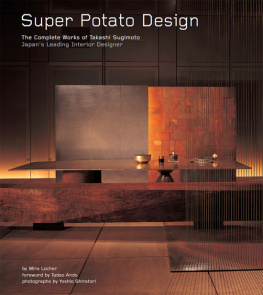

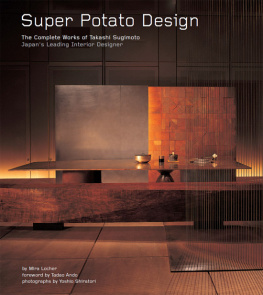

Rooms enclosed by massive blocks of aji granite, enormous tables of granite and thick wooden planks, the sudden appearance of vast screens of bamboo and wood such was the latest project I saw by Takashi Sugimoto of Super Potato inside a massive high-rise building in Tokyo. There, amidst works of other radical designers, each striving to develop magnificent futuristic spaces competing to achieve the greatest sense of lightness, Sugimotos creation stood alone, as it formed a completely different atmosphere.

The materials Super Potato uses with an emphasis on stone, steel, and wood, impart scale and form beyond the customary. In the nonchalant ease of arrangement, logical harmony is unintended the materials collide with each other, and in doing so each secures its respective place. The energy generated from that violent impact seizes the attention of people casually passing by and does not let go. Within the brilliant, fragile, artificial contemporary city overflowing with light, only Sugimoto can create a layered discontinuity that seems to summon an ancient spirit. Yet Sugimoto does not succumb to the conventional experience of old designs, and this is the result of his super power.

I cannot recall exactly when and where I first met Takashi Sugimoto. However, ours has been a very long friendship. I think perhaps we were introduced toward the end of the 1960s by the late Shiro Kuramata. It was probably at Judd in Nogizaka, or some such place that Kuramata had designed. I was in my twenties and had not yet become an established architect. I still had not discovered my correct place in society, and all I had was courage and conviction, but I believed it was a time when society felt the hope and possibility that a path for the future would be revealed. I spent each day searching for creative stimulus, and was fortunate to meet many different people who influenced my path in life.

World renowned for his concrete and glass buildings, Osaka native Tadao Ando established his architectural practice in 1970 and is the recipient of numerous awards, including the prestigious Pritzker Prize in 1995 and the AIA Gold Medal in 2002.

At that time, Kuramata had already acquired a reputation as a cutting-edge designer. When I occasionally visited from Osaka, he would always introduce me to someone interesting, such as Tadanori Yokoo Among the people I became acquainted with, Takashi Sugimoto stood out as an extremely idiosyncratic individual. Although he had only recently graduated from the Crafts Department of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music, he already had a strong presence and made a significant impression on all he met. He was a man who drank sak animatedly and ate well. His expression of friendly innocence, mixed with a stubborn refusal to accept others opinions, remains strongly etched in my mind. Since then, whenever I hear that a project has been completed by this man, four years my junior, I make a point of going to see it.

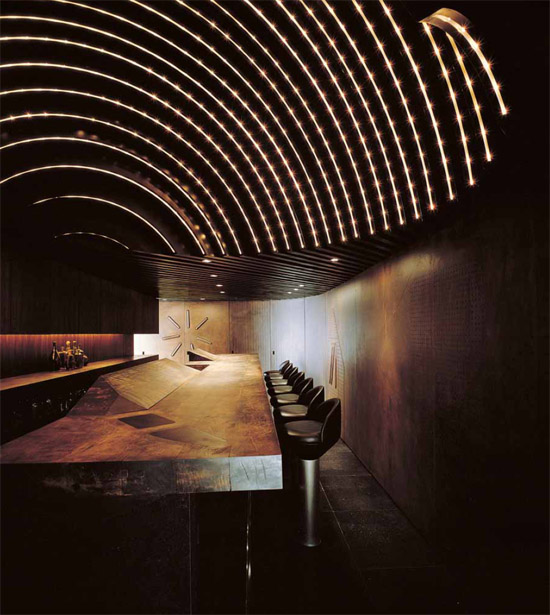

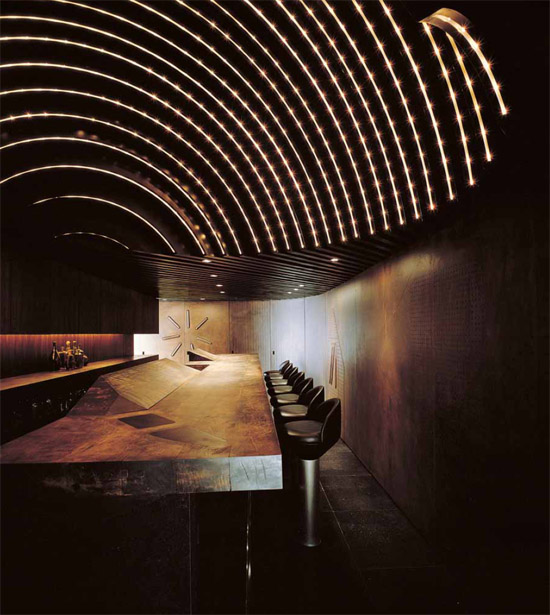

I think the first project I saw was the pub Maruhachi. Half of the ceiling and walls had been left as exposed concrete; the other half was covered with squares of steel, like louvers. From Sugimotos personality, I expected a potent design, but the rusticity and power of this work was greater than I had imagined. Contrasting materials each transmitted a message, yet at the same time the space felt complete, and it had the persuasive power to put visitors at ease. Subsequently, I often visited another of Sugimotos masterpieces, the bar Radio, originally made in 1971. I recall the attraction of the powerful space, which seemed to be generated from the dynamic immensity of industrial creation, but yet brought forth by human hands. There, rusted metal wall surfaces and a counter fashioned of thick boards of gnarly cherry wood created a mysterious harmony.

For people, including myself, who were more concerned with the expression of the time, the central focus was the modern design that flourished in the West. In my mind, we set forth from that place to discover our own self-expression. However, from there Sugimotos work developed in an entirely different dimension, as if he were cultivating a novel world.

The bar Radio, with its sculptural wood counter and metal walls, shocked the Tokyo design world when it opened in 1971, but quickly became a favorite haunt of artists and designers.

Contrasting materials merge in many of Super Potatos projects, including the entrance to Brasserie-EX. Welded metal panels of varied shapes create a unique entry door.

In direct opposition to this, Kuramatas work revealed exacting aesthetic considerations brought about by a keen design sensibility. Compared with the intense light which radiated from Kuramatas work an abounding sense of transparency completely liberated from the force of gravity which seemed to negate the designs existence Sugimotos work was completely other, as though a creeping profound blackness was released. To speak without fear of being misunderstood, I believe it was just like comparing the refinement of the Yayoi culture

Of course, the essence of a composition is based on the formative language of the time. When reduced to line and plane, there emerges a design composition filled with an extreme feeling of tension. However, the essence starts from abstract existence, passes through Takashi Sugimotos corporeal thinking and sensibility, and at the moment it is given tangible materiality and scale, a kind of discord is created. Each part of the composition has its own existence, at times in opposition to another, thereby uniting unstable atmospheres which begin to control place. Such primordial space can only be produced by Super Potatos Sugimoto from his own natural design approach. The industrial process is restrained to the utmost, materials are used in their natural state wherever possible, and the properties of diverse materials are exploited. Abutting stone, one very thick wood plank has its cross-section exposed. A bar counter is formed from one plank of roughly cut wood, its knots remaining. Sugimotos eye for choosing materials is superb.