Beacon Press

Boston, Massachusetts

www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books

are published under the auspices of

the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

2004 by Charles C. Calhoun

All rights reserved

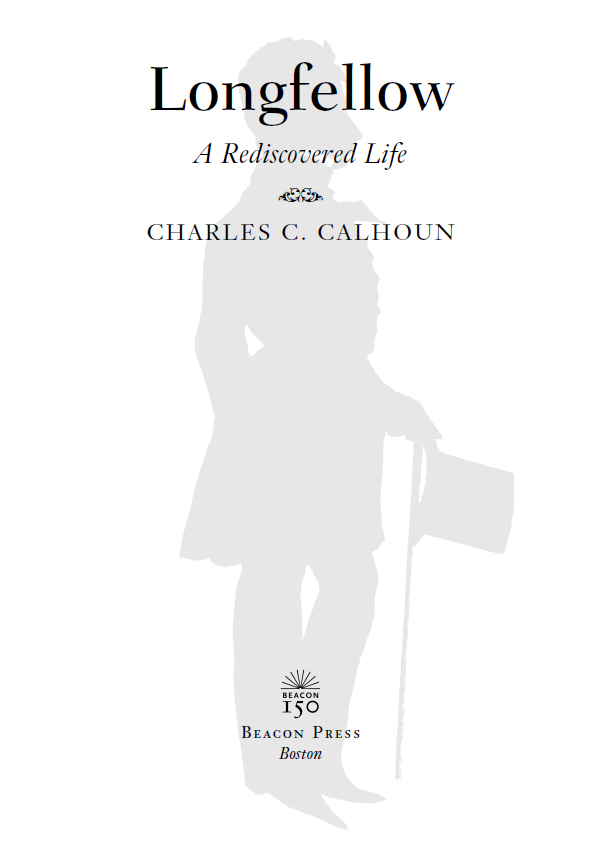

Frontispiece: M. August Edouart, silhouette of Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow, 1841. Courtesy National Park

Service, Longfellow National Historic Site.

Grateful acknowledgment for production assistance to Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

Composition by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services

Text design by Dean Bornstein

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Calhoun, Charles C.

Longfellow : a rediscovered life / Charles C. Calhoun.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

eISBN 978-0-8070-7041-3

ISBN 0-8070-7026-2 (cloth)

ISBN 0-8070-7039-4 (pbk.)

1. Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, 18071882.

2. Poets, American19th centuryBiography. I. Title.

PS2281.C25 2004

811.3dc22 2003025980

For Michael Horvath

INTRODUCTION

I N S EPTEMBER OF 2002, the National Park Service rededicated the Longfellow National Historic Site, the house at 105 Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Henry Wadsworth Longfellow lived from 1837 until his death in 1882. The event marked not only the thirtieth anniversary of public ownership of the property, but the completion of four years of badly needed restoration made possible by the Save Americas Treasures Act of 1997. Under a large tent on the lawn where Longfellows children had often played, some three hundred guests heard writers, politicians, federal officials, musicians, and schoolchildren pay tribute to a man whose name most Americans still recognize, but whose work scarcely anybody reads.

For a moment that afternoon, something else seemed restored: the Longfellow houses centrality in our culturethat intermingling of poetry and politics, of architecture and music, of cultural power and sense of public duty that the Craigie House had represented for about forty years in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The senior senator from Massachusetts recalled how his mother encouraged all the Kennedy children to learn The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere by heart. The junior senator from New York, Hilary Clinton, said that lines from A Psalm of Lifebut to act, that each tomorrow/Find us farther than to-day...had sustained her in her legislative career. Senator Clinton confirmed that Edward Kennedy had indeed recited Paul Revere from memory before Senator Robert Byrd, chair of the Appropriations Committeewho had recited it back to him, during the hearings on the funding bill.

Historian David McCullough evoked the ghosts of an earlier periodthe dark winter of 177576 when General Washington lived in the house and pondered the fate of American independence. Former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky said that Longfellows poetic project had been to make it newit being the sense of national identity that Americans of his day were still struggling, violently in 186165, to define. Members of the Boston Pops played the Largo from Dvorks Ninth (with its echoes of Hiawatha), and a soprano sang Charles Ivess haunting setting of The Childrens Hour.

And then it was over. Like the Arabs in The Day Is Done, someone eventually folded the tent and silently stole away.

Was this celebration an anomaly, or does Longfellow still live, even on the margins of our culture? If he does survive, whether as a diffuse poetical influence or as some broader cultural force, why do most people (literary historians included) know so little about him? There has long been a need for a comprehensive account of his life and career, written for the general public but drawing on a generation of new scholarship in history, literature, and the study of national identity.

The problem, of course, is that Longfellow was so very nice a man. He did not sleep with his sister, grow addicted to opium, have to flee college because of his gambling debts, cruise the waterfront, sire an illegitimate child abroad, or drink himself into dementia. He did not, in other words, behave the way the public has come to hope great poets will behave. While his life had an uncommon share of personal triumph and personal tragedy, his days in general were so placid, his livelihood so secure, his contemporary fame so universal, that in time he came to be seen as a symbol of everything that a writer should not be.

And that is where we find him today. To the extent that nineteenth-century poetry survives only in the classroom, Longfellow has dropped off the charts. He has never recovered from the battering he received at the hands of the Modernists, and he rarely caught the attention of the new, politically engaged scholarly communities of the 1980s and 90s (when he did, it was usually as a reminder of the complacencies, moral and aesthetic, of the successful white male Eurocentric poet-craftsman). Not that he ever really disappeared. He still has the respect of some practicing poetsread, for example, the enthusiastic essay by Dana Gioia in the Columbia History of American Poetry (1993) or Pinskys tributes to him as a Dante translatorand his words are ineradicably lodged in the mind of every American of a certain age who had to memorize The Wreck of the Hesperus or The Village Blacksmith in school. Others, innocent of Victorian poetry, nonetheless say they have shot an arrow into the air or passed like ships in the night or seen footprints on the sands of time or unwittingly echo the dozen or so other Longfellow quotes that have become part of the language. In a more general cultural sense, anyone outside of southern Louisiana who bites into some pan-blackened Cajun catfish or listens to zydeco is paying tribute, at only a slight remove, to Longfellows role in rescuing the Acadians from historical oblivion.

Longfellow is not only a more admirable poet than his twentieth-century detractors would have admitted; his most enduring cultural achievement is to have created and disseminated much of what we think of as Victorian American culture. That we still have conflicted feelings about this culture seems evident, especially in the field of sexual and religious politics. Yet we need to recognize over how large a field Longfellow operated. He played a central role in establishing New Englands cultural hegemonyin the sense that Americans were persuaded that America was New England writ large. He served as a major conduit into this country for European culture, from the radical German romanticism of the 1830s through his Dante studies in the 1860s and 70s. In turn, he represented the best of the new American culture to sympathetic Europeans. He did much to inspire Colonial Revivalism in architecture and the decorative arts in the 1870s, just as he had helped to popularize Medieval Revivalism in the 1830s and 1840s. He virtually invented the Evangeline story, the foundational myth of modern Acadian culture in Canada, Maine, and Louisiana. He supplied his fellow citizens with such emblematic literary characters as Hiawatha, Paul Revere, Priscilla Alden, and Miles Standish. He expressed in his work, and represented in his life, a style of masculinity in bold contrast to the Social Darwinists and muscular Christians of the next generation. However genteel and unthreatening his verse seems to us, he did produce over a long career an alternative vision to the America of the relentless market economy.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION