Loves of

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE

by Philip McFarland

NONFICTION

Hawthorne in Concord

The Brave Bostonians

Sea Dangers

Sojourners

FICTION

Seasons of Fear

A House Full of Women

Loves of

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE

Philip McFarland

Copyright 2007 by Philip McFarland

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation therof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Engraved portrait of Harriet Beecher Stowe, from a photograph taken in 1868, courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Published simultaneously in Canada Printed in the United States of America

FIRST PAPERBACK EDITION

eISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4866-8

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

08 09 10 11 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for

Don Cantor

and

Charlie Burlingham

dear loyal friends for more than fifty years

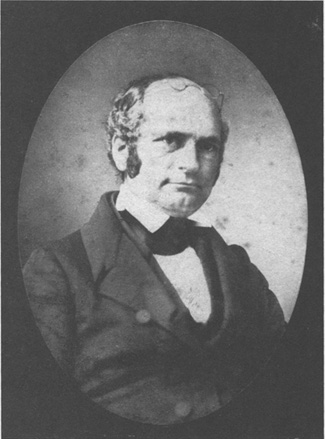

CALVIN

If you were not already my dearly loved husband, I should certainly fall in love with you.

Harriet Beecher Stowe to Calvin Stowe, 1842

CALVIN ELLIS STOWE, C. 1840

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

1

WESTWARD BOUND

Start with a coach lumbering westward over country roads and its occupants singing. The year is 1832, in mid-October. After a week in Philadelphia, one of those travelers would recall some seventy years later, we chartered a big, old-fashioned stage, with four great horses, for Wheeling, Virginia, and spent a week or more on the way, crossing the Alleghenies, before ever a railroad was thought of, and enjoyed every minute of the way. At least we children did, with brother George on the box shouting out the stories he got from the various drivers, and leading us all in singing hymns and songs. Fully alive and fresh from Yale at age twenty-three, George was keeping busy in the breeze topside, chatting with the stage driver, urging papers of religious uplift on chance passersby, and leading his family below in song, up to nine voices in their chorus all together. Another of the number, twenty-one-year-old Harriet Elizabeth Beecher, described the same scene with the journey still in progress: the obliging driver, good roads, good spirits, good dinner, fine scenery, and now and then some psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, for with George on board you may be sure of music of some kind. She, too, spoke of her older brothers distributing his tracts along the highway, peppering the land with moral influence; and after they had stopped for the evening at a village inn, Harriet took care to account for the party present one by one. She was writing back home and wanted her sisters family in Hartford to picture the scene.

See them, then, gathered in the front parlor of a Pennsylvania tavern. Father is opposite, seated at the table reading. Kate is writing a letter to that married sister who has chosen to stay behind in her settled life in Connecticut. Young Thomas, eight years old, sits beside his father making an entry in a journal of his own; and, wrote Harriet, ten-year-old Isabellawho will recall this odyssey after three-quarters of a centuryhas her little record too. George meanwhile stands ready to begin his contribution to the letter that Kate is composing, while, unmentioned, Aunt Esther, along with Harriets stepmother and the youngest, James at four, may have been off in their bedchamber resting, all of them after a days travel stopped at the village of Dowington, some thirty miles beyond Philadelphia.

They were bound for a new life together in the Queen City of the West, still many days ahead at the end of a long road. Father was fifty-seven. Thus advanced in age, the indomitable Lyman Beecher had picked up these of his family who wanted to come and was setting out to begin life anew in Cincinnati. Earlier, he and Katehis eldest daughter, Catharinehad scouted out the lay of the land, venturing west this past spring of 1832, and had liked what they saw. I know of no place in the world, Catharine had written, well pleased, from the scene, where there is so fair a prospect of finding every thing that makes social and domestic life pleasant. Already a couple of relatives from back east were established with their families in the thriving riverport of 30,000 people. Indeed, Catharine had reassured her correspondent at home, Cincinnati is a New England city in all its habits, and its inhabitants are more than half from New England. As for Father, I never saw, she went on, such a field of usefulness and influence as is offered to him here.

All his adult life Catharines father had made himself useful, first as the minister in a remote Long Island village during ten years at the start of the century; next for sixteen years as the minister of Litchfield, a prosperous town in western Connecticut; then over these past six years as minister of the Hanover Street Church in Bostons North End. But now, toward the end of his sixth decade, the nationally known Reverend Lyman Beecher had been offered a new, wonderful opportunity to serve both God and his country. For some time he had been thinking about the West in any caseIf we gain the West, all is safe, he assured Catharine in 1830; if we lose it, all is lostwhen word reached him of a new seminary being established in Cincinnati, Ohio. A benefactor out there had donated sixty acres of land two miles beyond the city on which to erect the Lane Theological Seminary, and $70,000 had been pledged for buildings and staff, provided that the celebrated Dr. Beecher could be persuaded to come from Boston to teach in and serve as president of the institution; as he is the most prominent, popular, and powerful preacher in the nation, he would immediately give character, elevation, and success to our seminary, draw together young men from every part of our country, secure the confidence and co-operation of the ministers and churches both east and west of the Alleghany Mountains, and awaken a general interest in the old states in behalf of the West.

Dr. Beecher learned of the trustees hopes to his enormous joy. I had felt and thought, and labored a great deal about raising up ministerswhat work could be more useful than that?and, he remarked of the invitation later, the idea that I might be called to teach the best mode of preaching to the young ministry of the broad West flashed through my mind like lightning. I went home, and ran in, and found Esther alone in the sitting-room. Esther was his maiden half sister, who lived with the family. I was in such a state of emotion and excitement I could not speak, and she was frightened. At last I told her. It was the greatest thought that ever entered my soul; it filled it, and displaced every thing else.

During these early years of the nineteenth century, the rapidly changing West was creating abundant work for the likes of a devout evangelical such as Lyman Beecher. Catholics, newly arriving, appeared to threaten all that vast region; the Mississippi Valley must be saved for the old faith, for Beechers brand of Protestantism. Cincinnati, for instance, founded along the Ohio River in 1788, had already become home to a congregation of some 100 Roman Catholics in scarcely three decades, by 1819; and in the single, more recent year of 1829, the swelling band of German and Irish proselytizers had managed to lure 150 Protestants of the river town over to popery, to that gaudy theological despotism whose laity were not even allowed to read the Bible, whose doctrines of celibacy and distaste for the flesh seemed at war with the family, whose allegiance ultimately was paid to a potentate in far-off Rome. A vast number of Americans viewed all this as a matter of the gravest concern. Dr. Beechers great motive in going to Cincinnati, his daughter Harriet would later flatly aver, was to oppose the influence of the Roman Catholic church in everyway. For Beecher was a Protestant evangelical, and thus his job, his duty, his lifes work was the saving of souls; on those terms he would wage battle against the Catholics out west, proselytizing for his own faith with a vigor that surpassed their own.

Next page