Contents

Also by

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall

LIKE A FAMILY:

THE MAKING OF A SOUTHERN

COTTON MILL WORLD (coauthor)

REVOLT AGAINST CHIVALRY:

JESSIE DANIEL AMES AND

THE WOMEN S CAMPAIGN AGAINST LYNCHING

SISTERS

and

REBELS

A

STRUGGLE FOR

THE SOUL OF

AMERICA

JACQUELYN

DOWD HALL

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2019 by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall

All rights reserved

First Edition

Portions of Chapter One first appeared in Open Secrets: Memory, Imagination, and the

Refashioning of Southern Identity by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. Copyright The American Studies

Association. This article was first published in American Quarterly 50, no. 1 (1998): 109124.

Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Portions of Chapter Three: Lest We Forget first appeared in You Must Remember This:

Autobiography as a Social Critique by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. Copyright Jacquelyn Dowd Hall.

This article was first published in The Journal of American History 85, no. 2 (1998): 439465.

Portions of Chapter Four: Contrary Streams of Influence first appeared in To Widen the

Reach of Our Love: Autobiography, History, and Desire by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. Copyright

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. This article was first published in Feminist Studies 26, no. 1 (Spring 2000):

23047. Reprinted with permission.

Portions of Chapter Nine: Writing and New York first appeared in Women Writers, the Southern

Front, and the Dialectical Imagination by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. Copyright The Southern

Historical Association. This article was first published in The Journal of Southern History LXIX, no. 1

(Feb. 2003), pp. 338. Reprinted with permission by The Southern Historical Association.

Portions of Chapter Eleven: The Heart of the Struggle first appeared in Like a Family: The

Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World by Jacquelyn Hall, Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, James

Leloudis, Lu Ann Jones, and Christopher B. Daly. Copyright 1987 by the University of North

Carolina Press. Foreword and afterword 2000 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used

by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions,

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Barbara M. Bachman

Production manager: Anna Oler

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd, author.

Title: Sisters and rebels : a struggle for the soul of America / Jacquelyn Dowd Hall.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, [2019] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018057931 | ISBN 9780393047998 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Lumpkin, Katharine Du Pre, 18971988. | Lumpkin, Grace, 18911980. |

Glenn, Elizabeth Elliott Lumpkin, 1880 or 18811963. | SistersGeorgiaBiography. | Women,

WhiteGeorgiaBiography. | Women authors, AmericanBiography. | Women political

activistsUnited StatesBiography. | Group identitySouthern StatesHistory20th

century. | Southern StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. | United States

Intellectual life20th century.

Classification: LCC F291.L89 H35 2019 | DDC 305.800975/0904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018057931

ISBN 9780393355734 (eBook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To my husband, Bob Korstad, whose faith sustained me,

and to the students

who contributed so much to this book

CONTENTS

SISTERS AND REBELS

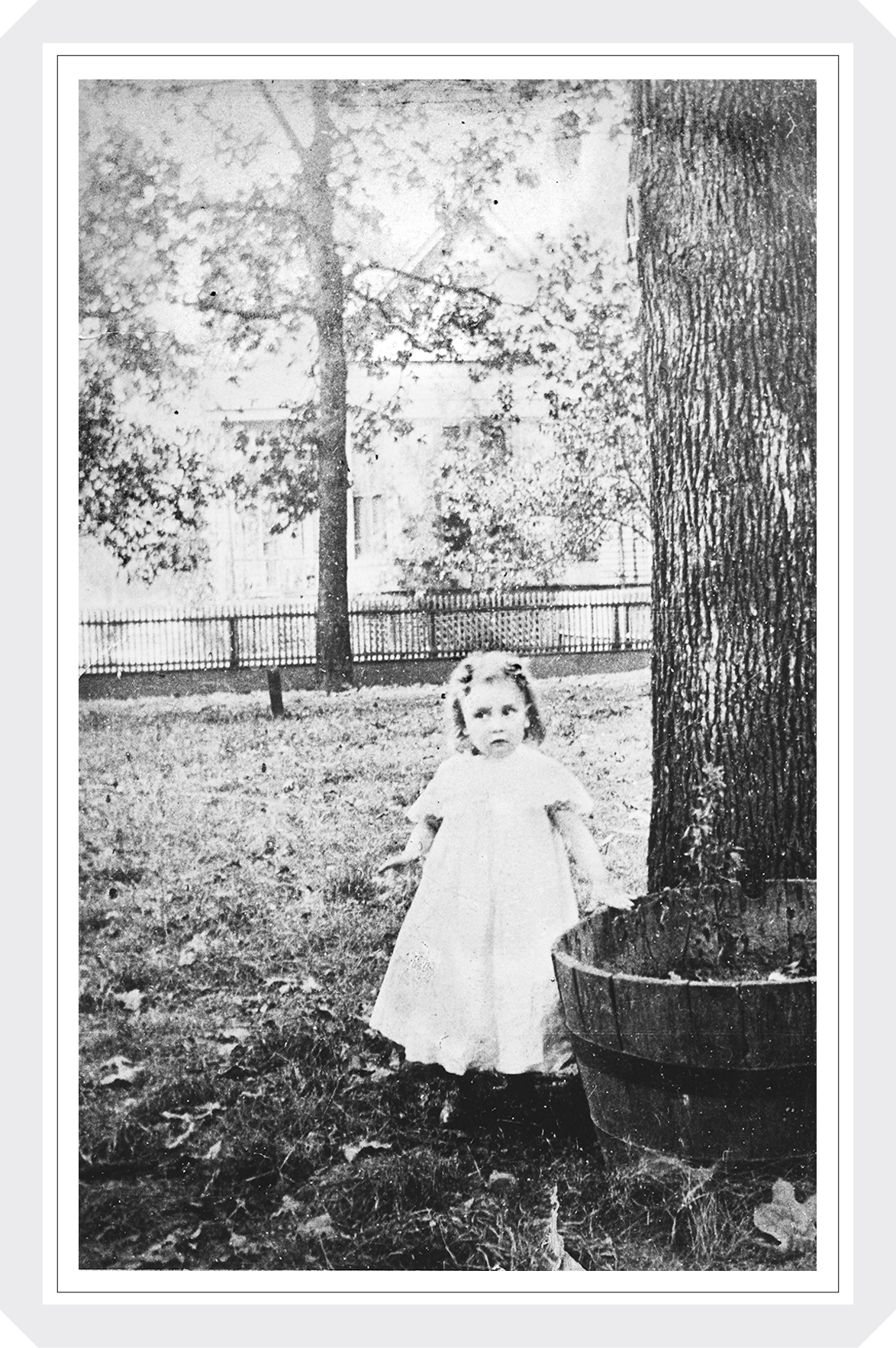

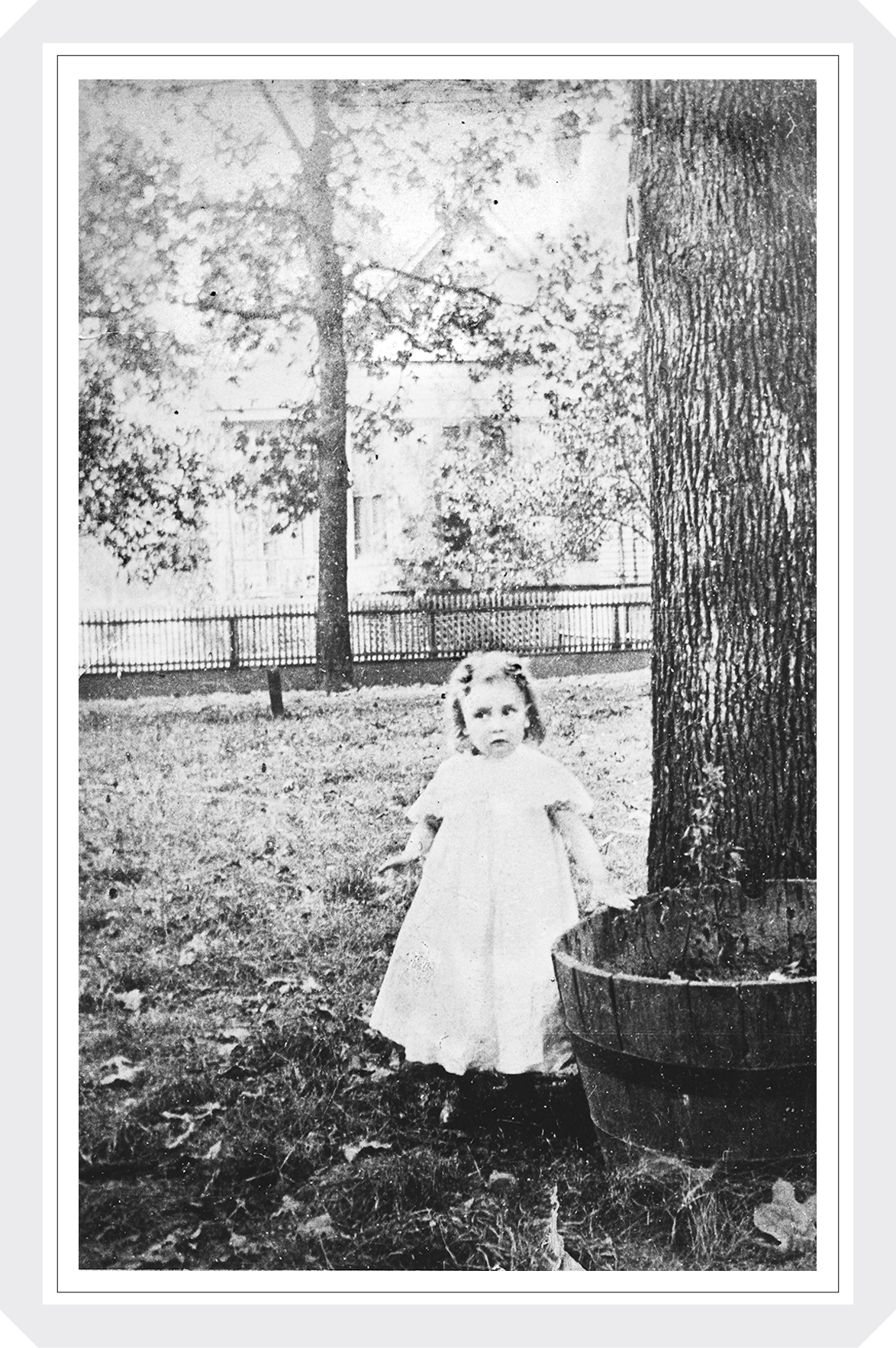

Katharine Du Pre Lumpkin on campus of Brenau College (now University), Gainesville, Georgia, 1900.

W HEN KATHARINE DU PRE LUMPKIN S AUTOBIOGRAPHY , The Making of a Southerner (1946), appeared in paperback, she chose for the cover a turn-of-the-century image of herself as a child. The girl in the photograph seems incandescent, from her cloud of blond hair to her long, lacy dress. Weeds brush the childs feet; her hand rests on the edge of a huge wooden barrel half-filled with dead leaves. Swaddled in whiteness yet confined by a dark, spiky fence, she is a daughter of the Old South, but there is no remnant here of a treasured plantation past, not a jasmine or a magnolia in sight. She glances to her right, with a doubtful, questioning expression. She is poised to step out of the frame.

I first stumbled upon The Making of a Southerner in the early 1970s while writing a dissertation about a white southern womens antilynching crusade. I saw Katharine as a figure who had inherited that crusades antiracist banner and carried it forward, passing it on to the student activists of my generation. Taking her stand with scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois and C. Vann Woodward, she had chipped away at the myths of southern history. But unlike the revisionistsindeed, unlike most historians to the present dayshe placed a woman at the center of southern past. Taking herself as her subject, she sought to show how both sexism and racism are grounded in the socialization of the child.

To me Katharines book was like summer lightning. Subdued but evocative, it backlit another world. I admired the honesty with which

Born into a former slaveholding family in 1897, Katharine was, as she tells us, dipped deep in the cult of the Lost Cause as a child. Emerging full force in the wake of the late nineteenth-century white supremacy campaigns, that self-serving memory of the southern past romanticized slavery and reconfigured the Civil War as a struggle, not to preserve human bondage, but to uphold states rights. It also demonized Reconstruction as a tragic era of Negro rule that justified disfranchisement and segregation. No lesson of our history was taught us earlier, Katharine remembered, and none with greater urgency than the either-or terms in which this was couched: Soldiers might perish, slavery might end, mansions might crumble, but as long as whites retained their dominance over blacks the Souths cause had not been lost.

Katharines effort to free herself from that legacy began in earnest when she encountered liberal Christianity and the social sciences at a small but vibrant womens college in her native region. She left the South briefly to study at Columbia University, returning in 1920 to spearhead the YWCAs campaign to build an interracial student movement in the face of Jim Crow. She left again five years later, eventually settling with her partner, the radical Smith College economist Dorothy Wolff Douglas, in Northampton, Massachusetts. Braving the job market in the late 1920s, just as professionalization and discrimination combined to stamp the social sciences as a masculine preserve, she experienced at first hand the dashed hopes of academic women, whose numbers declined steadily over the next forty years.