Copyright

Copyright 1941, 1969 by Arthur Bernon Tourtellot

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2014, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Farrar & Rinehart, New York, in 1941.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tourtellot, Arthur Bernon.

The Charles / Arthur Bernon Tourtellot ; illustrated by Ernest J. Donnelly.

p. cm.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-78947-7

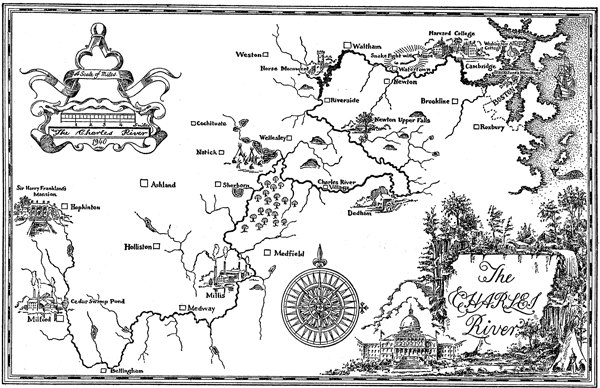

1. Charles River (Mass.) 2. Charles River Valley (Mass.)History. 3. MassachusettsHistory. I. Donnelly, Ernest J. (Ernest John),1973, illustrator. II. Title.

F72.C46T7 2014

974.4dc23

2013037150

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

49294X01 2014

www.doverpublications.com

The River of Life

I T was Ralph Waldo Emerson, the wisest man to walk in the valley of the Charles, who likened man to a river whose source is hidden and who moved, like the river, to eventual freedom. It was Emerson, too, who feared that, if the race of man ever died off, it would die of civilization. And if the calm ghost of Emerson has gone far back in time or come forward in this same valley, the years have proved his wisdom. For he would have encountered, in one direction, the simple, idyllic life of the Algonquins. But in the other, he would have come across a web of ideas and convictions that led to intricate philosophies that flourished for a while and then passed away. He would have seen top-heavy industries rise throughout the valley and then topple in the dust of depression. Yet through it all he would have seen freedom as the goal of the valleys history, the quest of the poets and philosophers, and the fixed star of tradesmen along the riverbank, of printers, grist-millers, shipwrights, and those who plowed the fields and hewed the trees.

Quineboquin, the Algonquins called the Charles, meaning circular, and that is the way mans life in the river valley has been, moving from the wild free dom of the Indian through the tragicomic quest of the white man, who brought with him all his crippling institutions and then went systematically about inventing other institutions to break them down. The way of the red man came to its end early, for the Indian failed when the test came, probably because he knew too little of the trick of organization. But the way of the white man in the valley goes on. Some things he has tried which, far from setting him free as he dreamed, have brought him tumbling back to earth, so that he has had to begin again. And other things, rooted in three centuries of living here in the valley, have grown strong and are achieving their missions: the colleges have endured, and so have the songs of the poets and the words of the philosophers, the stubborn and ceaseless rumbling of the press. The young still walk upon the riverbanks and dream; and the old walk slower and remember. The moon still rises, in some places shining down on deserted mills and converting the hard daylight tragedy of blind ambitions into the soft emptiness of shattered dreams, and in other places shining down on the waters of the river as they leap over the rocks with the maple and ash and oak their only witnesses still. This last is the river the poets knew and loved, the river that Lowell and Longfellow stood meditating over and up which the wry little physician Holmes rowed away from his patrician patients.

But the Algonquins knew it long before that, for to them it was the River of Life. They, too, had their poets and their philosophers; and if they did not know as much of the letter of Plato as those who came after them in the river valley, they knew more of Platos spirit. Through the years they evolved a host of legends which taught them the meaning of life, and they learned how to live. They sought the key of creation, too, in common with the prying curiosity of all mankind about things that do not concern them; and they came out of the whirlpool with a creed of passing wisdom.

In earliest times, the Algonquins believed, all the face of the earth was covered with water, and everything that lived floated about on a raft. Chief of all the animals was the Great Rabbit, who was the Great Spirit himself in mortal shape. After the raft had floated about aimlessly for a time, which might have been days or centuries, the animals were growing restless, so that the Great Rabbit saw clearly that there must be land to accommodate them and give point to their lives. So he called the beaver and sent him overboard into the depths, telling him to bring back with him a handful of earth. But the beaver went down and came up with nothing. Then the Great Rabbit called the otter and told him to go down and see what he could find. But the otter came up with nothing. Then the Great Rabbit considered the possible alternative measures he could employ to get hold of a little bit of earth and could light upon nothing of worth. As he sat in troubled silence there in the midst of the endless waters with the animals surrounding him and the raft floating impotently about, a little female muskrat came to him and offered to take a dive down into the deep. But the other animals, particularly the beaver and the otter, laughed at her and derided her, The Great Rabbit, however, gave her permission to try, and the little muskrat hopped off the edge of the raft and disappeared below the surface of the water. All that day and all that night and throughout the next day until evening, nothing was seen of the enterprising muskrat. Even the Great Rabbit had given her up as lost. But at the second twilight the body of the muskrat popped to the surface. They hauled her abroad the raft and found that the muskrat was unconscious; but in her paw she clutched a little ball of mud.

The Great Rabbit took the bit of mud and molded it in his hands. It grew larger and larger, first into an island, then a mountain and then the earth itself. The rabbit walks around and around it, looking to search out imperfections. He walks around it still, for it does not yet satisfy him. Thus, the Great Spirit envelops the earth forever.

The other animals meanwhile found homes for themselves, some in the hills, some in open fields, and some near the rivers in quiet nooks. Moreover, the Great Rabbit made trees by shooting his arrows into the earth and transfixing them with other arrows to form branches. Last of all, he rewarded the muskrat by taking her as his mate, and out of the union sprang the race of man. The Great Rabbit was the personification of the Great Spirit, and the muskrat the personification of earth. So the Algonquin saw his race as the creation of both spirit and matter; and if he recognized the earth as his mother, he recognized the spirit of eternity as his father. He conferred on the latter the name Missabos, which came from the same route as his words for Light, Dawn, and the East.