Longfellow in 1854, age 47. Engraving after a portrait by Samuel Laurence (courtesy National Park Service. Longfellow HouseWashingtons Headquarters National Historic Site, LONG 20579).

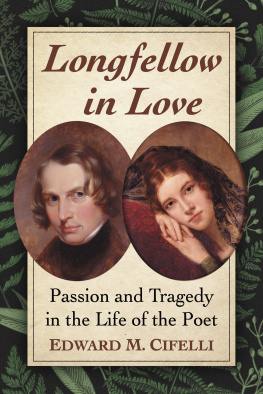

Longfellow in Love

Passion and Tragedy in the Life of the Poet

EDWARD M. CIFELLI

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3423-4

2018 Edward M. Cifelli. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

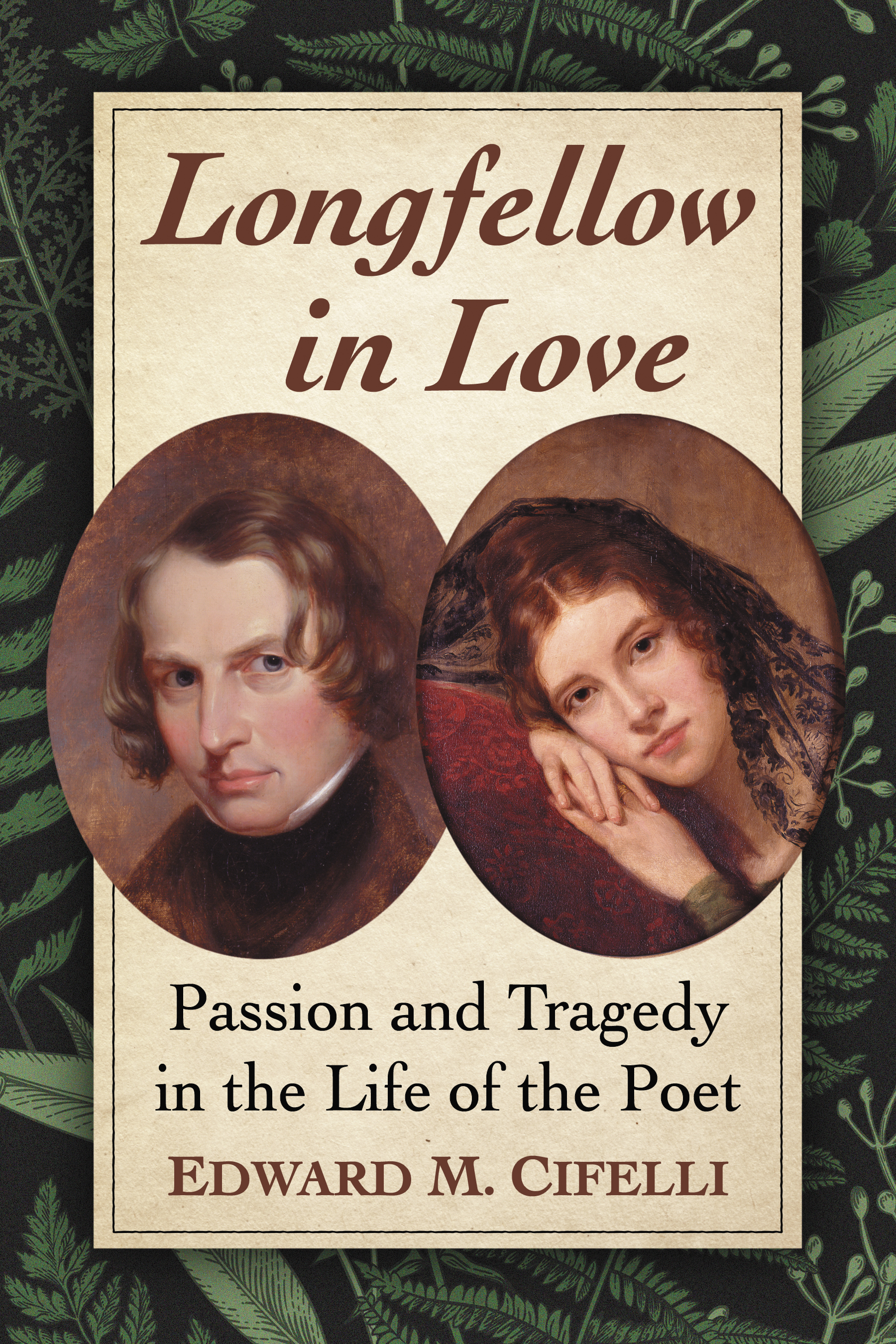

Front cover: (left) Henry W. Longfellow by Cephus Giovanni Thompson, 1840; (right) Frances Appleton by G.P.A. Healy, 1834 (both paintings courtesy of the National Park Service)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

I cannot overcome the passion. I cannot change my nature.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 18141843

My nature craves sympathynot of friendship, but of Love. This want of my nature is unsatisfied. And the love of some good being is as necessary to my existence as the air I breathe. To tell you the whole truthI saw in Switzerland and traveled with a fair ladywhom I now love passionately (strange, will this sound to yr. ears) and have loved ever since I knew her. A glorious and beautiful beingyoungand a woman not of talent but of genius! Indeed a most rare, sweet woman whose name is Fanny Appleton.

Letter to George W. Greene January 6, 1838

Acknowledgments

Scholarship on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow began in the middle of the nineteenth century and has continued, despite fluctuations in his reputation in the twentieth century, through to the current revived interest in the twenty-first. It is a privilege to single out a few scholars for special thanks, Andrew Hilen first and foremost for his six-volume Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Others include Samuel Longfellow, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Herbert S. Gorman, Newton Arvin, Edward Wagenknecht, and more recently, Dana Gioia, Charles C. Calhoun, and the scholar most responsible for the current Longfellow revival, Christoph Irmscher. It is harder to estimate the place of Louise Hall Tharp, the prolific popular biographer whose work on the Appleton family is exhaustive and readableand from what I can determine, mostly dependable. She was an amateur, not a professional, university-trained scholar, but in 1959 she received an honorary Doctorate in Literature from Northeastern University, a well-deserved honor to a scholar who learned her craft and professionalism on the fly. I am grateful for the work she left behind on the Appleton family. I apologize to the many authors not named here, but the list of Longfellow scholars is long and impressive, and the best I can do to suggest the breadth of their interests and the depth of their studies is my bibliography. To them all I owe a debt of thanks.

For specific help on particular problems, I would like to send along my deep appreciation to the following people and institutions: From the Houghton Library at Harvard University: Leslie Morris, Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts; also from Harvard, Reference Librarians James Capobianco and Susan Halpert; from Saint Leo University Library (Dade City, Florida): Cristina Martinez; from the Longfellow House: archivist Christine Wirth; from the Pejepscot Historical Society: Rebecca Roche (now at the Maine Maritime Museum); from the Maine Historical Society, Jamie Kingman Rice and Sofia Yalouris; from the New York Public Library: Lea Jordan; from the Archibald S. Alexander Library, Rutgers University: Stephanie Bartz; from the Special Collections Department of the University of Iowa Libraries: Denise Anderson; from the Mississippi Quarterly: Managing Editor Laura E. West; from the Boston Public Library: Reference Librarian Tonya Stafford; and from the Zephyrhills Public Library in Zephyrhills, Florida, a full team of professionals and volunteers: Director Andi Figart (now at the New Port Richey Public Library), Peggy Panak, Debbie Lopez, Victoria DeGeorge, and Dede Hammond. I am also obliged to Gilbert Muller for help with a Frances Bryant reference. For psychological insights into Longfellow, thanks go to Dr. Frank Ancona, professor of literature and psychology, and Dr. Larry Lentchner, clinical psychologist. A special thanks goes to Tracy Bernstein at the Signet Division of New American Library, who put this book in motion when she asked me in 2003 to write a new preface to Evangeline and Selected Tales and Poems. Last, thanks to Samantha Halsey for her expertise and tireless work as a copy specialist. And yet, despite all the collective good work of these fine people and many others who have helped me along the way, errors have no doubt crept in. They are mine, of course, and mine alone.

Finally and happily, thanks to my family, to my daughters Lisa and Laura, to their spouses, Heather Strout and Steven Stibich, and to six wonderful grandchildren: Elizabeth Louise, Julia Rose, Madeline Jill, Joseph Edward, David Robert, and Thomas Patrick. Most of all, I owe more than I can say to the lovely Roberta Louise, my wife and partner for fifty-one years now. I dont know how I got so lucky.

Preface

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote poetry for a huge audience that lined up to buy his books on their publication dates. He became in the process our first full-scale literary celebrity, signing autographs by the thousands and speaking patiently and politely to fans from all over the world that came to his door or stopped him when he was out walking. He even answered fan mail. He was not just admired, but beloved by readers who cared both for his tightly built poems and the morally secure universe they were set in. It was personalpeople liked him and his poems.

All that popularity might suggest to some that Longfellow had to make intellectual or poetic compromises in order to secure the readers favor and to achieve public acclaim, but that wasnt the case. He was in fact uncompromising when it came to connecting readers to the glories of European history and artthe same sort of literary cross-fertilization T.S. Eliot, part of the Modernist generation that replaced Longfellows, insisted on in his famous Tradition and the Individual Talent. This historical sense, Eliot maintained, involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presencewhich was Longfellows stock in trade. By connecting readers of his own time to works from the Western literary tradition in his translations and in his poems, and also by preserving complicated verse forms native to a half dozen European literatures, Longfellow lived historical tradition by embracing it, praising the past by putting it into his present.

The self, however, gets lost in this sort of poetry. Eliot thought that was only natural, commenting that poetry is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality. Private, reserved, and restrained, Henry Longfellow kept his personal life to himself, which, of course, separated him from most twentieth-century poets who came after him, in both senses of the termlike the self-absorbed Confessionals for example, or the formalist-bashing Beats. Twentieth-century literary critics smugly dismissed the extraordinary success of Longfellow as the less-than-worthy achievements of a poet-entrepreneur. They agreed that what he needed was more emotion and less craft, more America and less Europe, more poverty and less profit. They thought they were attacking Longfellows poetry from the unassailable moral high ground, which proved to be, however, an ungracious and ungenerous position to occupy.

Next page