Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by John William Babin and Allan Levinsky

All rights reserved

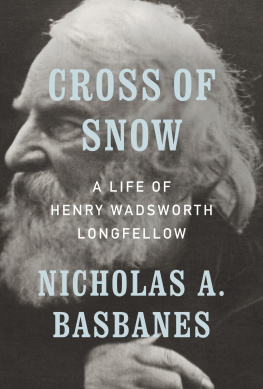

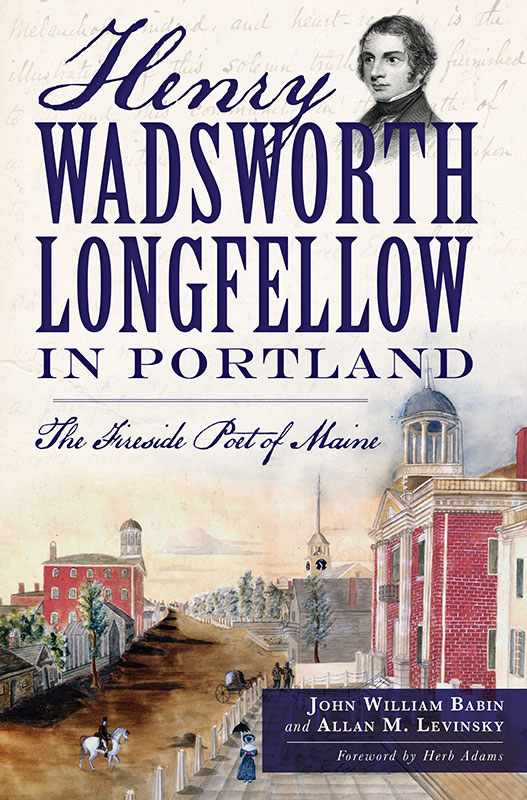

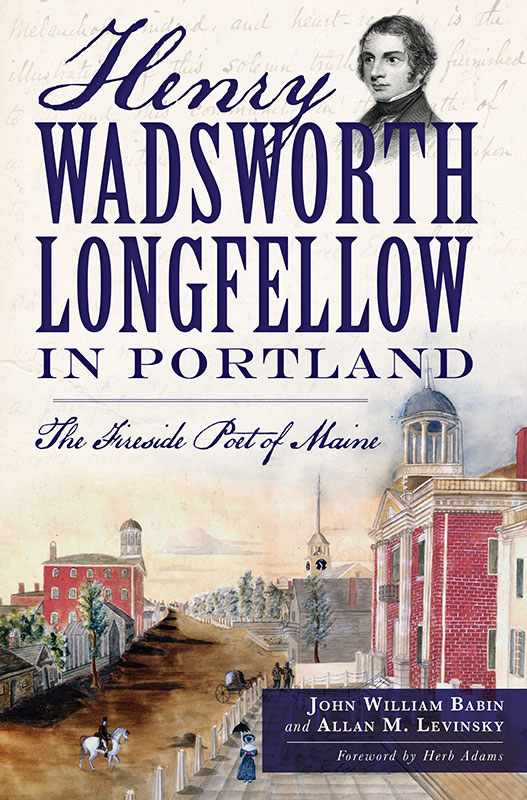

Front cover town image courtesy of the Collections of Maine State Museum and Maine Historical Society. Longfellow image courtesy of the George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine.

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.025.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015947041

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.499.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

As a teacher and tour guide, one of the best things about the Wadsworth-Longfellow House is that the family has never left it. No, not in the sense that spirits walk the hallsthough some say they do. In the sense that this was once a real home, a place of real personalities, of love, loss, tears and joys and a place where a family really lived real life. This aura lingersin that sense, the Longfellow house is uniquely a home, and a familys blessing still surrounds it.

All houses where people once lived, felt loss, knew joy and passed on are haunted houses, as wrote Longfellow in his older years. I have no doubt that he was thinking about the home he knew as a boy.

Portland and the Wadsworth-Longfellow House were born together, in 1786. That year, the tiny peninsula seaport separated from old Falmouth town and became infant Portland. Also that same year, cartloads of fresh brick were hauled uphill from local brickyards to the cellar site along the dusty back road out of town, where General Wadsworth was building a new home so far from the center of things that it was considered a folly. But it was different then, and it is different now.

As an old Atlantic seaport, Portland is blessed with several remarkable mansion homes. Visitors can still see the George Tate House in Stroudwater, the home of the kings last royal mast agent and the very last mast agents house still standing in America. In town, the Victoria Mansion still awes visitors with the no-holds-barred rococo Gilded Age oak, frescoes, stained glass and palatial gilding worthy of its builder, Mainer and hotel magnate Ruggles Morse. It is the best remaining example of high Victorian living left in America. Tate was an eighteenth-century millionaire and Morse a nineteenth-century multimillionaire. Their houses are meant to awe as symbols of status and grand mansions that still make for memorable visits. Yet one wonders: were there people here? Was this ever a hearth and a home?

Longfellows boyhood house was exactly thatand it still is. It was once a crowed place and still feels so. Parents, children, in-laws, maiden aunts and visitors filled its three floors. Its sloping floors and favorite spots still feel a bit battered and beloved; well-lived rooms have a sense of smiles and lives worn with tears. Family clutter sits where it should be. It is as if the family is still there, just out of sight in the snug kitchen, happy to be hosts, pleased with visitors. The halls are open now but never really empty. The world that cannot be stopped still rushes by outside, but here the present pauses and takes its hat off at the door.

On the great stone front doorstep, young Zilpah Wadsworth, the poets future mother, once blushingly presented silk banners to the city militia. In the great parlor inside, once the biggest room in Portland, family members married, balls were danced and Henrys favorite flute still sits atop the family piano. (In the then-distant twentieth century, the infant radio station WCSH broadcast patriotic tunes played on that very piano, probably Maines first piano to take to the novel airwaves.)

A favorite room for the family, and for visitors still, is the dining room, small and snug, handy by the warm smell of the kitchen. Here, by day, Stephen Longfellow, the poets father, taught law to young lawyers-to-be; by night, books aside, the family dined around the crowded table in the glow of lamps and love. Even now, in low light, the room feels of family.

And upstairs, in the back bedroom, young Anne Longfellow, the poets sister, widowed in her youth, once sat by her fireplace wrapped in blankets and wept. By her room, in the plaster wall of the stairs to the third floor, a tiny girls handprint remains. Her nameElizastill exists above it in childish handwriting. She died young; it is all that is left of her.

Her nephew, Henry, passed by it every night of his young life climbing to his boyhood bedroom. As an old man, his shoulders brushed by it every night on visits as he mounted narrow stairs to his favorite adult bedroom above. What did he think about the long-lost aunt he never knew?

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, by then the most famous man in America, climbed those stairs the last summer of his life while visiting in 1881. By the spring of 1882, he had passed on. It fell to Anne, his younger sister, to hold the memories of the house until the twentieth century, when she left it to us. She changed nothing, and nothing since has changed inside.

Once, from her front windows, you could see Portland Head Light flashing far down the coast. From the back windows, one could hear waves washing against the shores of Back Cove. Now the city has hemmed everything inincluding the memories, safely inside. We need a few places like this. America is a very young country, as the world goes, and has a long trail ahead. Homes like this carry the musing visitor forward, as much as back, in thought.

The Freudians may drill Longfellow and come up dry. The poet wrote about an America he loved for a world he believed in, and he spared in his verses none of the personal pain life dealt him (and it dealt him plenty) nor any of the sentimental optimism about mankind that hasty cynics dismiss as all of him. They are wrong.

When Longfellow passed on in 1882, the elderly Ralph Waldo Emerson, sweet but senile, was led up to view his old friend one last time. That man has a beautiful face, sighed Emerson, but I have quite forgotten his name.

America has never forgotten Longfellow, and he never forgot the Portland homea home, in every sensethat framed his life and made his memories warm. The family called the house the Old Original. Thoughtful workers here are lucky people. Visitors can still find the past, but also the future, if they look quietly enough.

And all, in many ways, will find this one ancient home that is never alone or empty.

HERB ADAMS

Maine Historian

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my mom, Gloria Ann Latini Babin: thanks, Mom! Ill never forget the first time you brought me to the Longfellow House when I was but a wee lad. I still have the same feeling today as I did as a child walking up the stairway to the second floor. Some things you never forget! To Sofia Yalouris, image services coordinator for the Maine Historical Society: without your hard work and guidance, this book would have never been done.

Next page