Sufism and American Literary Masters

SUNY series in Islam

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, editor

Sufism and American Literary Masters

Edited by

Mehdi Aminrazavi

Foreword by

Jacob Needleman

Cover art from Fotolia

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Diane Ganeles

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sufism and American literary masters / edited by Mehdi Aminrazavi ; foreword by Jacob Needleman.

pages cm. (SUNY series in islam)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5353-8 (hc.: alk. paper)

1. American poetryIslamic influences. 2. Sufi poetry, AmericanHistory and criticism. 3. Sufism in literature. 4. Muslims in literature. 5. Islam in literature. 6. Mysticism in literature. I. Aminrazavi, Mehdi. II. Needleman, Jacob.

| PS166.S85 2014 |

| 810.9'382974dc23 | 2014028931 |

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Mitra, my daughter for her resilience and courage in light of adversity

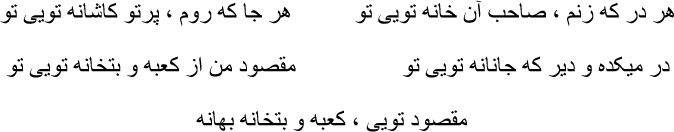

Thou art the dweller of every house on whose door I knock,

Whereever I sojourn, Thou art the Light of the door way.

Be it tavern or monastery, Thou art its soul of souls.

In praying to the Kabah or the house of idols, I have Thee in mind,

The purpose is Thou, the Kabah and the idol house are but an excuse.

Baha al-Din Amili

Contents

Jacob Needleman

Mehdi Aminrazavi

Leonard Lewisohn

Mansur Ekhtiyar

Marwan M. Obeidat

Parvin Loloi

Farhang Jahanpour

Mahnaz Ahmad

Massud Farzan

Arthur Versluis

John D. Yohannan

Phillip N. Edmondson

Mehdi Aminrazavi

Alan Gribben

Foreword

The essays in this book offer fascinating revelations concerning the correspondences between Islamic mysticism and the work of such quintessentially American writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, and Mark Twain. As such, this book is likely to take an important place in the academic fields of American studies and comparative literature. But its significance transcends the limits of academia and touches on the deepest and most troubling questions of our present era. And in so doing, it reminds us of the noble purpose of literature in the development of the mind.

Our world its seems exists mainly under influences that inevitably lead to division and conflict, even as on the surface of events globalization and advancing technology often inspire dreams of a united human family. It has become clear that in our contemporary civilization, despite all hope to the contrary, fear, anger, and avarice, the ancient devils that set human beings against each other, remain the real lords of life, to appropriate an Emersonian phrase. The essential question, which is now a literal matter of life and death, therefore remains: Where and what are the forces that can lead individuals, peoples, and nations toward an acceptance of each other in fact as well as in dreams, and inspire an awareness of the ultimate oneness and value of life? The themes of the following essays hold fundamental clues to the answer to this question.

Those clues reside in the juxtaposition of the words Sufism and the names of some of the most iconic American writers of the nineteenth century. Sufism is generally understood as both a doctrine and practice embedded in the religion of Islam. These essays taken as a whole posit that somewhere behind the historical, geopolitical, and philosophical incommensurabilities that now seem so harshly to separate Islam from the views of mainstream America, there remain significant traces of a philosophical convergence that resonates in some of the most American poetry in existence. A study of these traces not only opens a new avenue of mutual understanding between the Islamic and American souls, but will provide a springboard for a deeper understanding of the opportunities that literatures provides as a medium for reconciling seemingly intractable differences.

Ralph Waldo Emersons 1844 essay The Over-Soul remains one of the most eloquent examples of nineteenth-century transcendentalisms explication of Indian spirituality. Of particular influence was the doctrine of Atman, or Higher Self, which forms the essence of the human Self and is inseparable from Brahman, which forms the corresponding essence of the universal Self. Part of Emersons genius was his ability to reconsider such prototypical American values as the emphasis on pragmatism and individual agency in the light of spiritual, even esoteric reinterpretations of these values. Another case in point is Self-Reliance (1841), which opens with a dynamic characterization of the American ideal of individualism and self-determination and closes having reinterpreted such models as mere facets of the Higher Self within.

This kind of work constitutes philosophy, and indeed literature itself, at the height of their power: serving as reminders of humanitys higher identity, which is continually forgotten in the necessary life of action in the world. Through great ideas greatly expressed, literature enables readers to function, and even grow, in a cultural milieu that relies on a worldview and explanatory model that tend to reductionist absolutism, relativism, titillation, and the provocations of subjective morality.

Visionary works of philosophy and literature are among the cultural forces necessary to open our minds to the possibility of transforming human beings, by nature dangerously gifted animals, into instruments of conscience and compassion; yet open-mindedness is not in itself enough, and here the meaning of Sufism can perform an essential task. Sufism is indeed a system of ideas rooted in the great perennial vision of man and reality that lies at the heart of all the worlds spiritual traditions, but the contemporary, albeit modest, awakening interest in Sufism is directed mainly to its status as a practice leading to a higher state of Being. In short, Sufism is a Way. What is meant by that term is a guided inner struggle, in which a man or woman strives to emerge from a state of egoism, submitting to a supreme Goodness that is both idea and energy.

When the influence of Indian spiritual tradition was first appearing in nineteenth-century America, any information was almost entirely limited to purely philosophical content, with only fragmentary and speculative practical applications. In general, the discipline, the full practice of the Way, was known haphazardly, if at all. Even Hinduism, which mainly influenced the transcendentalists and contains the idea of the practice of a Way at its heart, was seen as pure philosophy with no central place in the day-to-day lives or writings of the American Transcendentalists.