AMERICAN RENAISSANCE

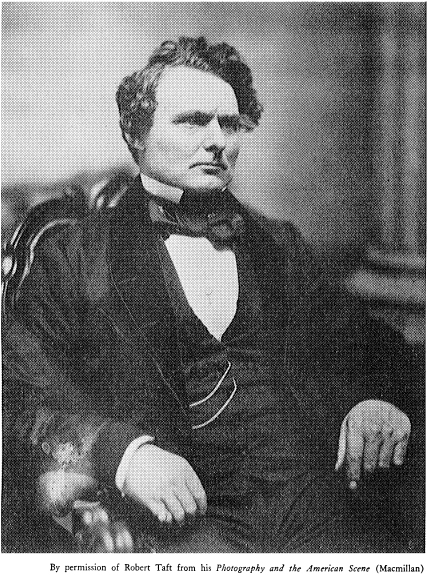

DONALD McKAY, Builder of the Flying Cloud, the Sovereign of the Seas, the

James Baines, and the Lightning.

DAGUERREOTYPE BY SOUTHWORTH AND HAWES (Boston)

American Renaissance

ART AND EXPRESSION

IN THE AGE OF EMERSON AND WHITMAN

F. O. MATTHIESSEN

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Oxford London Glasgow

New York Toronto Melbourne Wellington

Nairobi Dar es Salaam Cape Town

Kuala Lumpur Singapore Jakarta Hong Kong Tokyo

Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi

Copyright 1941 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

First published by Oxford University Press, New York, 1941

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1968

printing, last digit: 20 19 18 17 16

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FOR

HANNS CASPAR KOLLAR, formerly of Vienna,

and HARRY DORMAN, of Santa Fe, New Mexico,

WHO HAVE TAUGHT ME MOST

ABOUT THE POSSIBILITIES OF LIFE IN AMERICA

There is a moment in the history of every nation, when, proceeding out of this brute youth, the perceptive powers reach their ripeness and have not yet become microscopic: so that man, at that instant, extends across the entire scale, and, with his feet still planted on the immense forces of night, converses by his eyes and brain with solar and stellar creation. That is the moment of adult health, the culmination of power.

-EMERSON, Representative Men.

Men must endure

Their going hence even as their coming hither:

Ripeness is all.

marked by Melville in

his copy of King Lear.

METHOD AND SCOPE

THE starting point for this book was my realization of how great a number of our past masterpieces were produced in one extraordinarily concentrated moment of expression. It may not seem precisely accurate to refer to our mid-nineteenth century as a re-birth; but that was how the writers themselves judged it. Not as a re-birth of values that had existed previously in America, but as Americas way of producing a renaissance, by coming to its first maturity and affirming its rightful heritage in the whole expanse of art and culture.

The half-decade of 1850-55 saw the appearance of Representative Men (1850), The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of the Seven Gables (1851), Moby-Dick (1851), Pierre (1852), Walden (1854), and Leaves of Grass (1855). You might search all the rest of American literature without being able to collect a group of books equal to these in imaginative vitality. That interesting fact could make the subject for several different kinds of investigation. You might be concerned with how this flowering came, with the descriptive narrative of literary history. Or you might dig into its sources in our life, and examine the economic, social, and religious causes why this flowering came in just these years. Or you might be primarily concerned with what these books were as works of art, with evaluating their fusions of form and content.

By choosing the last of these alternatives my main subject has become the conceptions held by five of our major writers concerning the function and nature of literature, and the degree to which their practice bore out their theories. That may make their process sound too deliberate, but Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman all commented very explicitly on language as well as expression, and the creative intentions of Hawthorne and Melville can be readily discerned through scrutiny of their chief works. It has seemed to me that the literary accomplishment of those years could be judged most adequately if approached both in the light of its authors purposes and in that of our own developing conceptions of literature. The double aim, therefore, has been to place these works both in their age and in ours.

In avowing that aim, I am aware of the important books I have not written. One way of understanding the concentrated abundance of our mid-nineteenth century would be through its intellectual history, particularly through a study of the breakdown of Puritan orthodoxy into Unitarianism, and of the quickening of the cool Unitarian strain into the spiritual and emotional fervor of transcendentalism. The first of those two developments has been best sketched by Joseph Haroutunian, Piety versus Moralism: The Passing of New England Theology (1932). The whole movement will be genetically traced in Perry Millers monumental study of The New England Mind, the first volume of which (1939), dealing with the seventeenth century, has already extended the horizons of our cultural past. Another notable book could concentrate on how discerning an interpretation our great authors gave of the economic and social forces of the time. The orientation of such a book would not be with the religious and philosophical ramifications of the transcendental movement so much as with its voicing of fresh aspirations for the rise of the common man. Its method could be the one that Granville Hicks has inherited from Taine, and has already applied in The Great Tradition (1933) to our literature since the Civil War. An example of that method for the earlier period is Newton Arvins detailed examination (1938) of Whitmans emergent socialism.

The two books envisaged in the last paragraph might well be called The Age of Swedenborg and The Age of Fourier, Emerson said in 1854, The age is Swedenborgs, by which he meant that it had embraced the subjective philosophy that the soul makes its own world. That extreme development of idealism was what Emerson had found adumbrated in Channings one sublime idea: the potential divinity of man. That religious assumption could also be social when it claimed the inalienable worth of the individual and his right to participate in whatever the community might produce. Thus the transition from transcendentalism to Fourierism was made by many at the time, as by Henry James, Sr., and George Ripley and his loyal followers at Brook Farm. The Age of Fourier could by license be extended to take up a wider subject than Utopian socialism; it could treat all the radical movements of the period; it would stress the fact that 1852 witnessed not only the appearance of Pierre but of Uncle Toms Cabin; it would stress also what had been largely ignored

But the age was also that of Emerson and Melville. The one common denominator of my five writers, uniting even Hawthorne and Whitman, was their devotion to the possibilities of democracy. In dealing with their work I hope that I have not ignored the implications of such facts as that the farmer rather than the businessman was still the average American, and that the terminus to the agricultural era in our history falls somewhere between 1850 and 1865, since the railroad, the iron ship, the factory, and the national labor union all began to be dominant forces within those years, and forecast a new epoch. The forties probably gave rise to more movements of reform than any other decade in our history; they marked the last struggle of the liberal spirit of the eighteenth century in conflict with the rising forces of exploitation. The triumph of the new age was foreshadowed in the gold rush, in the full emergence of the acquisitive spirit.

Next page