American Metempsychosis

Emerson, Whitman, and the New Poetry

John Michael Corrigan

Fordham University Press

New York 2012

Copyright 2012 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Corrigan, John Michael.

American metempsychosis : Emerson, Whitman, and the new poetry / John Michael Corrigan. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8232-4234-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. American literature19th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Self-consciousness (Awareness) in literature. 3. National characteristics, American, in literature. 4. Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 18031882Criticism and interpretation. 5. Whitman, Walt, 18191892Criticism and interpretation. 6. Transmigration in literature. I. Title.

PS217.S44C67 2012

810.9353dc23

2011042866

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1

First edition

A book in the American Literatures Initiative (ALI), a collaborative publishing project of NYU Press, Fordham University Press, Rutgers University Press, Temple University Press, and the University of Virginia Press. The Initiative is supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more information, please visit www.americanliteratures.org.

Contents

I have benefitted from the support and friendship of numerous people while writing this bookand I would have been unable to persevere without them. I begin by thanking Alan Ackerman for his sure-sighted counsel and steadfast belief in this project; Malcolm Woodland whose warm words of confidence and encouragement I will not forget, coming as they did in times of difficulty and transition; and John Reibetanz whose fidelity to poetry has been an inspiration throughout. I also thank the faculty and administration of the English Department at the University of Toronto and acknowledge the funding of the Ontario government.

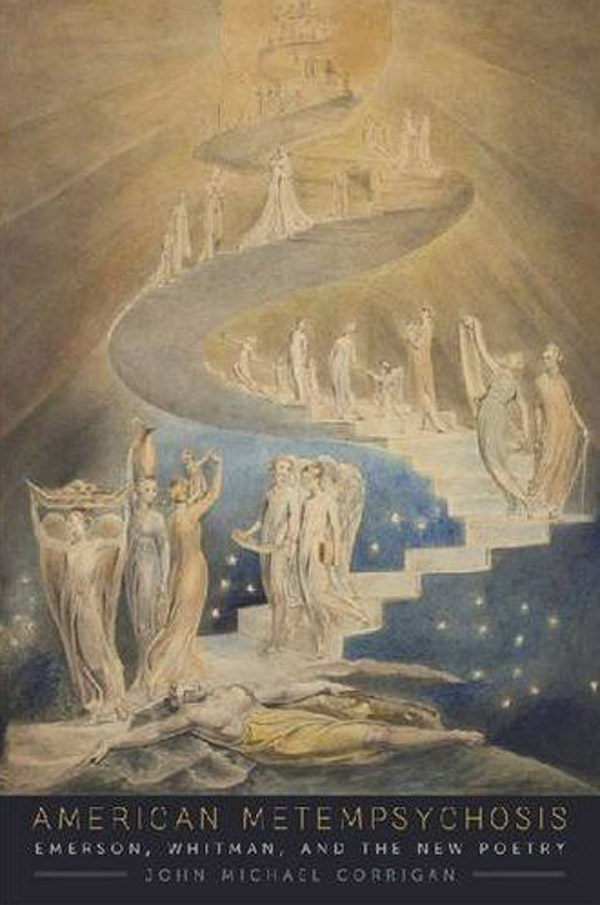

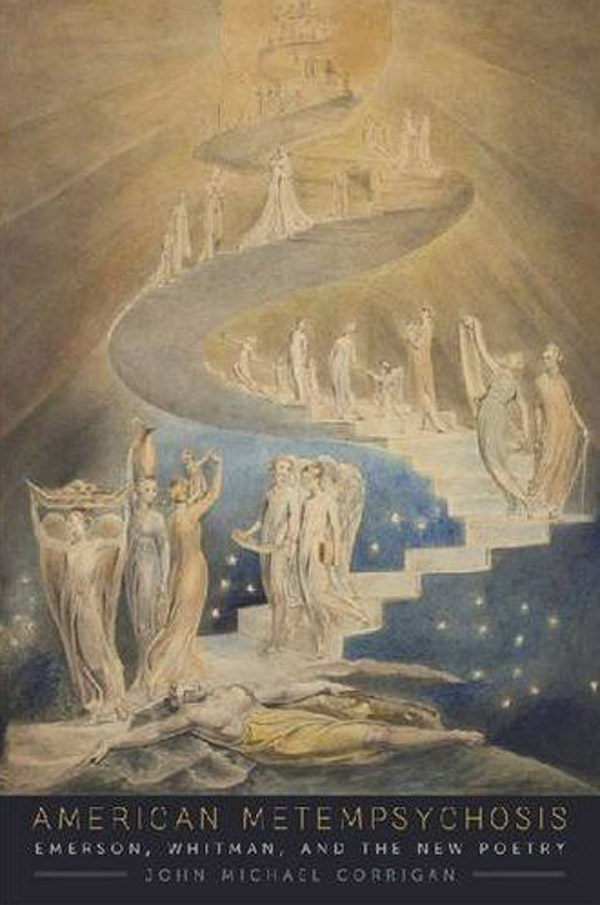

Portions of this book have appeared previously: sections of Chapters 4 and 5 in the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review (2011); parts of Chapter 1 in the Journal of the History of Ideas 71.3 (July 2010); and one section of Chapter 2 in Dionysius (2009). I gratefully acknowledge their permission to reprint. For the use of William Blakes Jacobs Ladder for the cover art, I thank the British Museum.

I thank Fordham University Press and the American Literatures Initiative, particularly Helen Tartar, Thomas C. Lay, Kathleen Sweeney, Tim Roberts, and Alex Giardino. I am also indebted to many others, Tony Brinkley, Betsy Erkkila, Jay Bregman, Elspeth Brown, Robert Berchman, Kodolnyi Gyula, and Sally Wolff-King.

To my parents, Kevin and Elena Corrigan, I owe a deepest debt of gratitude; my brother Yuri for his friendship and the many hours he spent reading and editing my writing; Maria and Sarah Corrigan for their love and support; and Jesse Archibald-Barber, a true friend. I would also like to thank Greg Glazov, Francis and Tess Corrigan, and their families. To my uncle Jamie Glazov, whose brotherhood has made me a better man, and to my grandmother Marina Glazov, our familys poet, I am truly grateful. Peggy Lee, who stayed by my side at the close of this project, thank you for your love and support.

I dedicate this work to my family, both the Corrigans and the Glazovs, and particularly to the memory of my grandfather Yuri Glazov.

In the painting Jacobs Ladder (1800), William Blake illustrates the nature of the Romantic reconception of human consciousness. At the bottom of the canvas, Jacob lies sleeping, his head resting by the foot of a spiral stair that circles upward through the star-filled sky and finally into the sun itself. Upon the stairway, the souls of angels and human beings pass each other, either descending to earth or ascending to heaven. In the Book of Genesis (28: 1122), Jacobs dream is a divine revelation: And, behold, the LORD stood above [the ladder], and said, I am the LORD God of Abraham thy father, and the God of Isaac: the land whereon thou liest, to thee will I give it, and to thy seed. Informed by centuries of mystical practice, Blakes ladder is not only an epiphanic event; it is a figurative map of the human psyche. Indeed, Blake foregrounds Jacobs sleeping body; in the background behind Jacobs head, the staircase rises upward, becoming in its climb the focal point of the watercolor. Jacob reclines, moreover, in the posture of crucifixion, the horizontal plane of the material body intersecting with the vertical dimension within or behind consciousness, which the ladder is intended to represent. Here, upon the ancient architecture of ascent, Blake plunges a whole spiritual cosmology into the internal life of consciousness, powerfully demonstrating the extent to which mysticism underpins the development of the modern self.

Blakes painting also exhibits a decisive Platonic influence, for his ladder is explicitly a ladder of love, much like the ladder of ascent from Platos Symposium. Midway on Blakes staircase, two lovers meet face to face, ascent and descent, the way up and the way down, united in their mutual embrace. By placing the lovers so centrally on the ladder, Blake underscores a whole tradition of ascent, which viewed the ladder as a structure of metempsychosis or reincarnation.

Where Blake followed certain esoteric and alchemical forms of thought by clothing spiritual mysteries in secret symbolism, Ralph Waldo Emerson made these mysteries not simply available to a wider audience;

In History, the leading essay of the First Series of Essays (1841), Emerson declares that the transmigration of souls is no fable,

In Self-Reliance, the essay that immediately follows History, Emerson writes that power resides in the moment of transition from a past to a new state, in the shooting of a gulf, in the darting to an aim (W 2: 40). Harold Bloom remarks that nothing is more American, whether catastrophic or amiable, than that Emersonian formula concerning power, to analyze the emergence of pragmatism and American literary modernism. Yet contemporary criticism has largely ignored the fact that Emersons very depiction of power as the souls transition from a past to a new state resides explicitly within a metempsychotic purview. Emersons attempt to collapse a whole mystical cosmos into the individual mind is not as unlikely an intellectual preoccupation as it might seem. New Englands Unitarian movement in the early part of the nineteenth century prepared for it by championing the domain of a new spiritual self capable of recognizing the God within through daily activity and self-reflection.

In his most famous sermon, Likeness to God (1828), William Ellery Channing, the most prominent voice of New England Unitarianism, argues that to grow in the likeness of God we need not cease to be men. This likeness does not consist in extraordinary or miraculous gifts, in supernatural addictions to the soul, or in anything foreign to our original constitution; but in our essential faculties, unfolded by vigorous and conscientious exertions in the ordinary circumstances assigned by God. Here, Reed anticipates Emersons metempsychotic mind in his depictions of how the self witnesses its own cognitive succession and comes to enact death and rebirth in the process.

Next page