C OMMENTARY

HENRY JAMES

ROBERT FROST

MATTHEW ARNOLD

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

HENRY JAMES

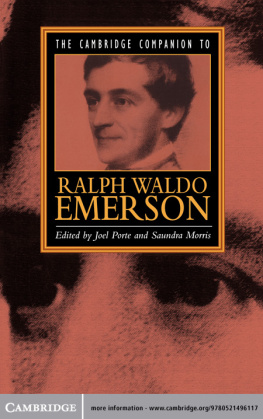

[Emerson] did something better than anyone else; he had a particular faculty, which has not been surpassed, for speaking to the soul in a voice of direction and authority. There have been many spiritual voices appealing, consoling, re-assuring, exhorting, or even denouncing and terrifying, but none has had just that firmness and just that purity. It penetrates further, it seems to go back to the roots of our feelings, to where conduct and manhood begin; and moreover, to us to-day, there is something in it that says that it is connected somehow with the virtue of the world, has wrought and achieved, lived in thousands of minds, produced a mass of character and life. And there is this further sign of Emersons singular power, that he is a striking exception to the general rule that writings live in the last resort by their form; that they owe a large part of their fortune to the art with which they have been composed. It is hardly too much, or too little, to say of Emersons writings in general that they were not composed at all. Many and many things are beautifully said: he had felicities, inspirations, unforgettable phrases; he had frequently an exquisite elegance.

From Partial Portraits (London: Macmillan and Co., 1888)

ROBERT FROST

I suppose I have always thought Id like to name in verse someday my four greatest Americans: George Washington, the general and statesman; Thomas Jefferson, the political thinker; Abraham Lincoln, the martyr and savior; and fourth, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the poet. I take these names because they are going around the world. They are not just local. Emersons name has gone as a poetic philosopher or as a philosophical poet, my favorite kind of both. I am disposed to cheat myself and others in favor of any poet I am in love with. I hear people say the more they love anyone the more they see their faults. Nonsense. Love is blind and should be left so.

From On Emerson, Daedalus: Journal of

the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 88.3 (Fall 1959)

MATTHEW ARNOLD

Emersons systematic benevolence comes from what he himself calls somewhere his persistent optimism and his persistent optimism is the root of his greatness and the source of his charm. One can scarcely overrate the importance of thus holding fast to happiness and hope. It gives to Emersons work an invaluable virtue. As Wordworths poetry is, in my opinion, the most important work done in verse, in our language, during the present century, so Emersons Essays are, I think, the most important work done in prose

In this country it is difficult not to be sanguine. Very many of your writers are over-sanguine, and on the wrong grounds. But you have two men who in what they have written show their sanguineness in a line where courage and hope are just, where they are also infinitely important, but where they are not easy. The two men are Franklin and Emerson. These two are, I think, the most distinctively and honourably American of your writers: they are the most original and the most valuable.

From Emerson, Macmillans Magazine 295 (May 1884)

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES

Those who lost themselves in the pages of Nature will find their way clearly enough through those of The American Scholar. It is a plea for generous culture; for the development of all the faculties, many of which tend to become atrophied by the exclusive pursuit of single objects of thought.

This grand Oration was our intellectual Declaration of Independence. Nothing like it had been heard in the halls of Harvard the young men went out from it as if a prophet had been proclaiming to them, Thus saith the Lord. No listener ever forgot that Address, and among all the noble utterances of the speaker it may be questioned if no one ever contained more truth in language more like that of immediate inspiration.

From Ralph Waldo Emerson

(New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1885)

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

The following is an entry in Thoreaus journal, believed to have been recorded in 1847.

[Emerson] seeks to realize a divine life; his affections and intellect equally developed. Has advanced farther, and a new heaven opens up to him. Love and Friendship, Religion, Poetry, the Holy are familiar to him. The life of an Artist; more variegated, more observing, finer perception; not so robust, elastic; practical enough in his own field; faithful, a judge of men. There is no such general critic of men and things, no such trustworthy and faithful man. More of the divine realized in him than any. A poetic critic, reserving the unqualified nouns for the gods.

Emerson has special talents unequalled. The divine in man has had no more easy, methodically distinct impression. His personal influence upon young persons greater than any mans. In his world every man would be a poet, Love would reign, Beauty would take place, Man and Nature would harmonize.

From The Heart of Thoreaus Journals, Odell Shepard, ed.

(New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1927)

READING GROUP GUIDE

Oliver Wendell Holmes called The American Scholar our intellectual Declaration of Independence. How does Emersons speech mirror our forefathers call for personal liberties? What does intellectual liberty entail and what kind of revolution does Emerson promote? What is his call to arms?

How is American historythe history that Emerson was living, witnessing, and documentingreflected in his observations and concerns? How might Emerson be reacting to the expansion of the American West, industrialization and its effect on both the landscape and rural society, and the rising tensions that would give way to the Civil War?

In a biography on Emerson, Robert D. Richardson hailed him as a prophet of individualism, an autarchist (a governor of the self) rather than the anarchist many thought him to be. Emerson said that a man can free himself only by obedience to his own genius. How is Emerson obedient to his own genius? How do his works reflect his individualism, and how does his message and his writing style break with those of many of his contemporaries?

Why should we not also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Emerson asks in the first paragraph of Nature. He seems to advocate a new American style in literature rather than the adoption of European style and thought. How would you define the American style that was developing at the time? How has the definition changed in the years that followed?

Many of Emersons essays were delivered as speeches or lectures (most notably, The American Scholar). How does this influence our reading of them? Based on his impassioned, instructive, and often inspirational bent, what assumptions can you make about Emersons audience?

Emerson began his career as a minister but later left the church and founded and embraced transcendentalism. To what degree do religion and spirituality inform Emersons prose, directly and indirectly, and how does Emerson differentiate the two?

Mary Oliver, in her Introduction, speaks of Emersons references to both Nature and nature. How does Emerson make this distinction? How would you? Are the two uses almost interchangeable? To which connotation is Emerson referring when he writes of the American Scholar, Therein [nature] resembles his own spirit, whose beginning, whose ending, he never can findso entire, so boundless.?

In his journal, Thoreau writes, there is no such general critic of men and things Emerson has often been categorized as a critic as much as he is a writer. How does Emerson critique his agethe literature, religion, politicsand what advice does he proffer?