ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As with all my writings, I am greatly beholden to my generous husband David Dunfield for his support and assistance throughout this project, including his careful reading of manuscript drafts and for his photography. I am very thankful to the many private collectors, artists, museum curators, and friends who arranged for me to use photographs at little or no charge, especially Colin MacKenzie and Stacey Sherman of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Thanks are also due to the many people with whom I had discussions about this project over many years, who helped in the procurement of photos and graciously allowed me to view and photograph their collections: Joan Baekeland, Cynthea Bogel, John Carpenter, Bill Clark, Sue Clark, Ellen Conant, Gerald and Alice Dietz, Bob and Betsy Feinberg, David Frank and Kazukuni Sugiyama, Hollis Goodall, Philip Hu, Junko Isozaki, Lee Johnson, Janice Katz, Yoshi Munemura of Koichi Yanagi Oriental Fine Arts, Rob Mintz, Andreas Marks, Julia Meech, Joan Mirviss, Halsey and Alice North, Beth Schultz, Fred Schneider, Joe Seubert, Takishita Yoshihiro, and Matthew Welch. Lastly, I want to acknowledge Eric Oey, publisher at Tuttle, for his insightful suggestions for text revisions, and his editors, Cal Barksdale, Sandra Korinchak, and June Chong, for making this book a reality. Carol Morland served as a perceptive and enthusiastic reader of a preliminary draft of the entire manuscript, and Mary Mortensen again, ably, prepared the index. I dedicate this book to my Mom, Ruth, and in memory of my Dad, Arthur Graham, with gratitude.

Emerging from the devastation of World War II, Japan entered an intense period of reconstruction in the 1950s. By the early 1960s, the countrys economic ascension was assured, propelled in large part by international successes in design-related industries. At that time, Japans long engagement with fine design and its sophisticated aesthetic concepts were attracting the interest of scholars, journalists, and museum curators in the West, who consistently used Japanese aesthetic terminology to describe the subject in books, popular magazines, and engaging exhibitions. This trend continues today. Usage of these Japanese words has proliferated for several reasons: many of the post-war foreign authors possess deeper knowledge of Japanese culture and linguistic competence than most of their predecessors; they have close connections with leading individuals in Japanese design communities; or they conduct research in collaboration with Japanese scholars who write about design issues.

This new post-war spirit of international cultural cooperation is nowhere more evident than in the mission of the International House of Japan, a non-profit organization headquartered in Tokyo. The I-House, as it is affectionately known, was founded in 1952 with support from the Rockefeller Foundation and other groups and individuals to promote cultural exchange and intellectual cooperation between the peoples of Japan and those of other countries.

This chapter introduces the most important and frequently deployed expressions describing Japanese design principles. It begins with a discussion of the omnipresent influence of the Katsura Imperial Villa in the early post-war period. Subsequent sections on individual words describe the history and continued evolution of their usage, introduce several overarching frameworks to help make sense of Japans wide variety of design principles, and offer a visual primer of contemporary arts that encapsulate the principles of these terms.

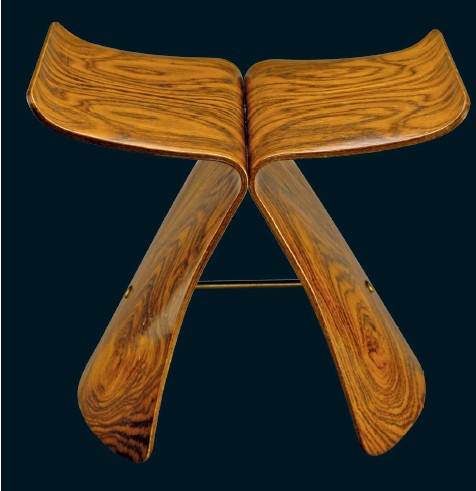

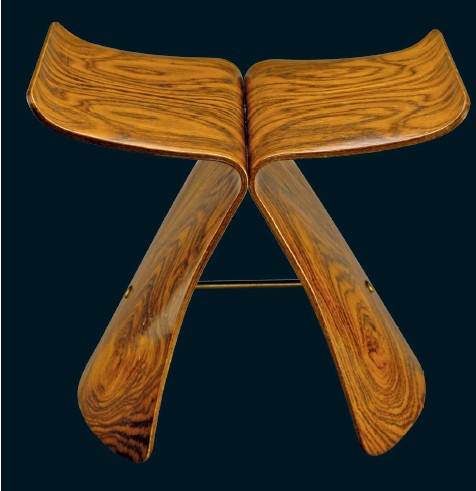

Plate 1-1 Butterfly Stool , 1956 . Designed by Yanagi Sri (19152011); manufactured by Tendo Mokko Co., Tendo, Japan. Plywood, rosewood, and brass, 37.9 x 42.9 x 31.8 cm. Saint Louis Art Museum. Gift of Denis Gallion and Daniel Morris, 82: 1994. This iconic stool epitomizes the melding of East and West design sensibilities in the early post-war years. The stool form and its material (bentwood plywood) are Western in derivation but the elegant, arching shape derives from a Japanese proclivity for fluid, playful forms. Its designer, Yanagi Sri, was the son of Yanagi Setsu (see page ), founder of the mingei movement. Like his father, he championed the beauty of functional, everyday objects.

Plate 1-2 Soy sauce container , 1958. Designed by Mori Masahiro (b. 1927); manufactured by Hakusan Porcelain Company, Hasami-machi, Nagasaki, Japan. Glazed porcelain, height 8 cm. Although a traditionally trained potter, Mori, in 1956, joined Hakusan Co. and embarked on a career that revolutionized the design of functional, mass-produced tableware. This classic soy sauce container, with its clean lines and graceful shape, remains in production today.

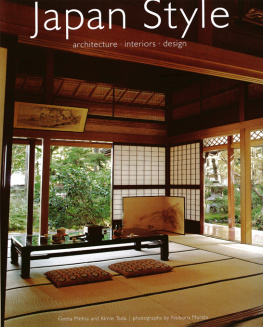

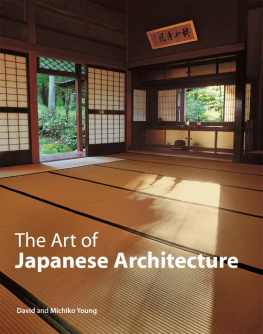

Plate 1-3 International House of Japan, Tokyo, Japan . Designed by Maekawa Kunio (19051986), Sakakura Junz (1901 1969), and Yoshimura Junz (19081997); originally completed in 1955; expanded in 1976 using Maekawas design; extensively restored and updated in 2005 by Mitsubishi Jisho Sekkei Inc. Photo courtesy of the International House of Japan. The adjacent garden, which predates the building, was completed in 1929 by famed Kyoto garden designer Ogawa Jihei VII (18601933), also known as Ueji, for the building that formerly sat on the site, a Japanese-style mansion built by samurai feudal lords of the Kyogoku clan. The 1955 building, although constructed of modern materials, was designed, in the spirit of pre-modern Japanese residences to harmonize with its garden. One of its most unusual features is its green rooftop, plantings that integrate the garden and the building.

KATSURA

REFINED RUSTICITY IN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

), it is undoubtedly the finest and the best preserved because of its association with the imperial court.

Plate 1-4 Central gate at the Katsura Imperial Villa , complex completed ca. 1663. Photo: David M. Dunfield, December 2007. The rustic rush and bamboo fence that leads to a humble looking thatched gate was probably once the compounds main entrance.

Beginning in the 1930s, both Japanese and foreign architects who adopted modernist design principles began to appreciate traditional Japanese residential design. Publications and lectures at that time by Bruno Taut (18801938; see page ) promoted it as the archetype of traditional Japanese residential architectural design. These architects particularly admired the flexibility and compactness of its spaces, the finely crafted details and structural elements made from natural materials, the modular design of building parts, the integral relationships between the buildings forms and their structures and between the buildings and surrounding gardens.

It was not until the immediate post-war period, however, that appreciation for Katsura truly took hold, largely through photographs in a seminal English language publication of 1960, jointly authored by architects Walter Gropius (18831969) and Tange Kenz (19132005). Ishimoto first visited Katsura in 1953 when he was accompanying Arthur Drexler (19261987), architect and long-time curator of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, on a fact-finding trip to Japan in preparation for a landmark exhibition of Japanese architecture at MoMA in 1955. For that exhibition, Yoshimura Junz, one of the architects of the International House of Japan, who accompanied Ishimoto and Drexler to Katsura, was commissioned to design a traditional Japanese residential building for MoMAs courtyard (the building, Shofuso, now resides in Philadelphias Fairmount Park), funded by John D. Rockefeller, III.