Shizen by itself means nature or natural. When the term is applied to arts and crafts, including modern designs, it also encompasses things that are made to look like they were made by nature.

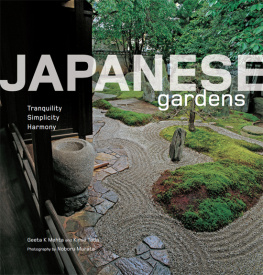

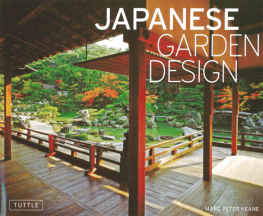

As is well known, one of the special skills that have long distinguished the Japanese is their ability to apply shizen characteristics, or the characteristics of nature, to the things they make, with landscaped gardens being one of the most conspicuous examples.

The obvious idea behind basing designs on shizen principles is that nature is the original designer and nature-made things are inherently appealing to human beings on both a conscious and subconscious level. We instinctively recognize that we have a physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual connection to nature; the more closely a product relates to certain aspects of nature, the more attractive it is to people. This especially applies to building materials, household furniture, utensils, and interior decorations. The Japanese learned this bit of wisdom a long time ago.

Shizenbi

(She-zane-bee)

Natures Standard of Beauty

The Spirit of Nature

Shizenbi means natural beautysomething that is at the core of Japanese aesthetics. Since the early Japanese believed that all things in nature had spirits and were spiritually connected, they were especially attuned to the appearance, character, and life of natural things.

The climate of the islands was temperate enough that it was conducive to a fairly comfortable lifestyle. And just as important, the scenic beauty of the islands was so sublime, so inspiring, that it had a fundamental influence on the sensibilities of the Japanese that was to have farreaching effects on the culture they developed over the millennia.

Among other things, the spiritual and physical relationship the Japanese had with nature led them to adopt both the outward beauty and the inner essence of nature as guidelines in their earliest arts and crafts.

Artists and craftsmen not only viewed the materials that they shaped into utilitarian objects as having spirits, they also treated their tools with extraordinary respect, not only in keeping them well maintained but also in handling them.

This spiritual attitude and behavior was significantly enhanced from the twelfth century on, when samurai warriors became the ruling class and administered all of the affairs of the country until 1868.

It was no great stretch for the samurai, already culturally instilled with the concept of material things having spirits, to begin regarding their swords as virtually sacred, and to treat them with the kind of respect generally associated with revered religious objects. (See Katana. )

Because the influence of the philosophical and ethical codes of the samurai gradually seeped into the common culture, the ancient Shinto concept of all things having spirits and deserving respect became even more deep-seated in the Japanese mind-set, and ensured that it would survive into modern times.

In present-day Japan master artists and craftsmen continue to consciously follow the ancient precepts of Shinto, and more traditional old-line companies continue to conduct Shinto rituals on special occasions in order to keep the spirits on their side.

Designers, engineers, and other professionals who do not consciously adhere to any of the old Shinto rituals in their day-to-day behavior nevertheless continue to be influenced by Shinto precepts in their work.

Wa

(Wah)

Harmony in All Things

The Law of the Land

Wa, the Japanese word for harmony, is now known by many people around the world, but what most people probably do not know is that the concept of harmony was so important in the traditional culture that it was one of the seventeen articles that are often described as Japans first constitution, written in A . D . 604. This law stated that all behavior was to be conducted in a harmonious mannernot only social behavior but business and political behavior as well.

The importance of harmony in Japanese life was to have a profound influence on every aspect of the culture, from the nature and use of the language to the daily etiquette of the people. Eventually, wa became the prime directive in Japanese behavior, often taking precedence over both logic and common sense.

Wa also played an equally important role in Japans arts and crafts. An incredible amount of time and effort were expended in making sure that all of the elements of the objectthe material, shape, surface, ornamentation, and so onwere absolutely harmonious.

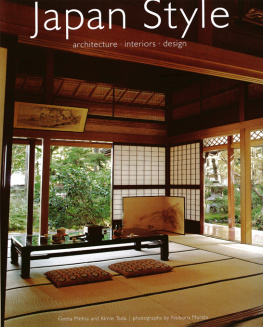

This physical expression of harmony is especially key to the appeal of Japanese gardens and to the interior design and decoration of traditional Japanese-style buildings, particularly private homes, ryokan inns, and ryotei restaurants.