Contents

Guide

Contents

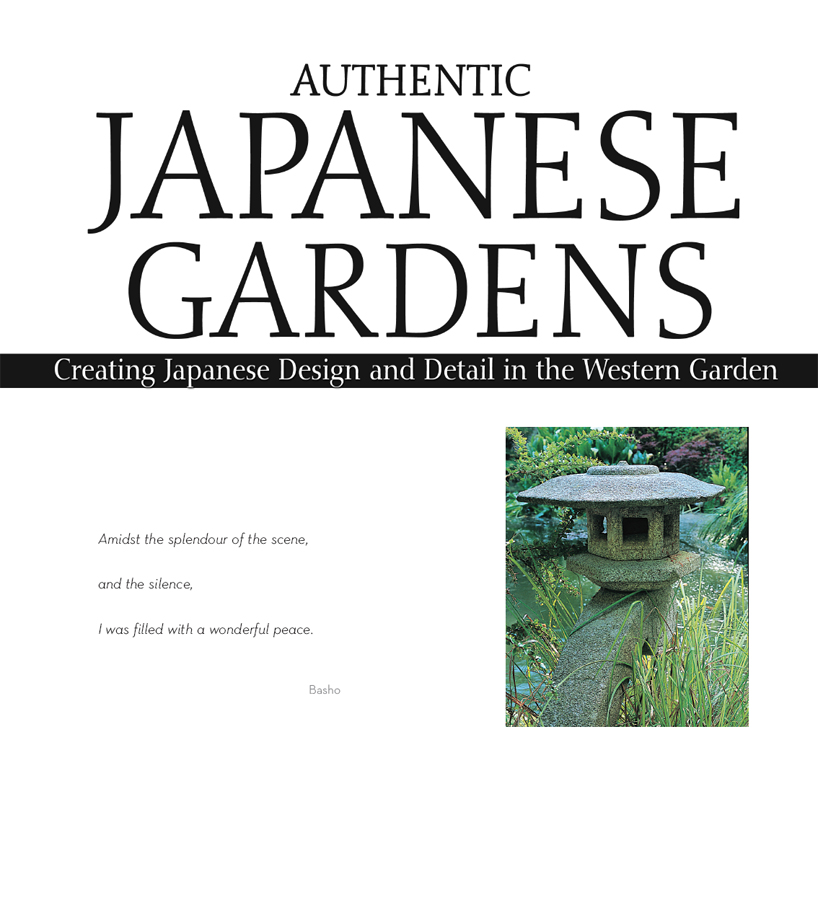

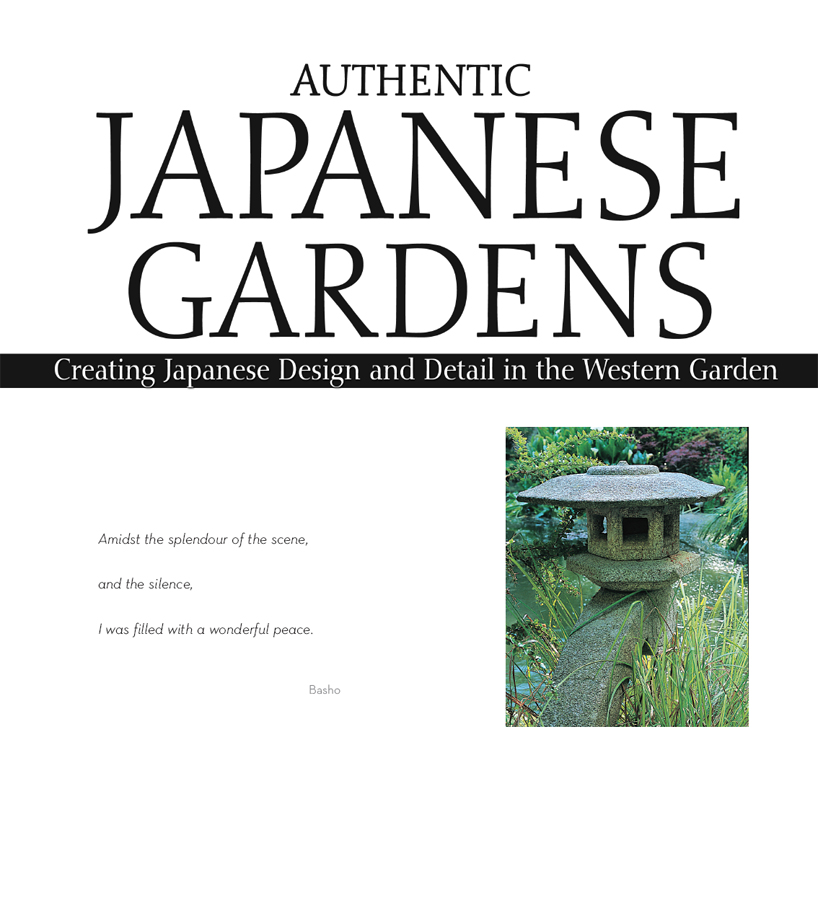

A kasuga-style lantern stands watch over a teahouse built in a secluded dell at Tatton Park, in Cheshire.

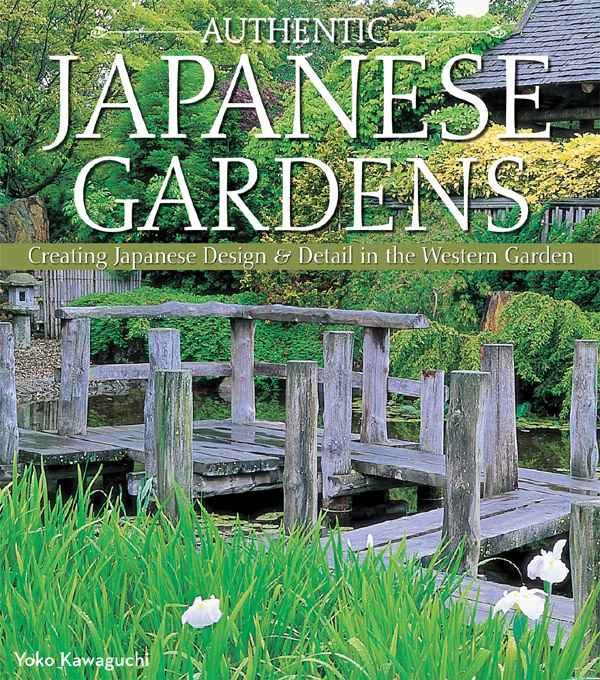

All over the world people are attracted to Japanese gardens, usually because they provide a tranquil environment, designed to give the impression of a natural landscape at its most serene. They possess a unique aura of calm, which derives from an economical, almost minimal use of materials, whether for building or planting.

A garden in the Japanese style is intended to offer peace and quiet contemplation, with restraint, order, harmony and decorum as the guiding design principles. It is an expression of love for living things, acceptance of the transience of Nature reflected in the changing seasons, and an inspired vision of the eternal.

From the tiniest courtyards to the grandest parks, Japanese gardens invite one to linger and savour their timeless quality.

Japanese-style gardens first became popular in the West in the second half of the nineteenth century. They were part of a craze for all things Japanese that swept Europe and America for about fifty years after the country first became more accessible. Until then, Japan had kept her doors tightly shut against the rest of the world with a brief exception in the seventeenth century, after which only a small group of Chinese and Dutch merchants, confined to a tiny island outside Nagasaki, were allowed to continue trading. The Dutch East India Company sent back to Europe Japanese porcelain and lacquered (japanned) chests and cabinets. What most people knew of Japan were the flowers, birds, pine-trees and islands painted on these household objects.

Rounded mountains, lushly forested, rise up out of a lake, forming a contrast with the austere elegance of Mount Fuji. For centuries, Japanese garden designers have sought to re-create the smooth lines and sinuous curves of the Japanese landscape. A vermilion torii gate marks the entrance to a Shinto shrine.

At first, it was the idea of Chinese rather than Japanese gardens that captured the imagination of Europeans, following the well-established fashion for Chinese motifs on porcelain, furniture and fabrics. When the first western accounts of real Chinese gardens began to appear in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, they sparked a vogue for mock-Chinese garden houses, which began in Britain and quickly spread to France and other countries. Pavilions and pagodas were used instead of classical temples, by then an established feature of English landscape gardens. In the western imagination, Chinese gardens were idyllic pleasure-grounds where languid ladies and gentlemen spent their time amusing themselves, drinking wine and playing musical instruments. When travellers returning from the Far East described real Chinese gardens as lacking the symmetry of European ones of the time (most of Europe was still under the influence of the French formal style), this apparent lack of constraint was welcomed by those eager to throw off the chains of French tradition. The charm of the Chinese style was thought to lie in the variety of scenery contained in one garden. Sir William Chambers (172396), the designer of the Chinese Pagoda and other buildings in Kew Gardens, felt that Lancelot Capability Brown (171583), the great eighteenth-century English landscape gardener, was going too far to a natural style of open landscape. In his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1772), Chambers proposed a greater use of contours, a more informal and varied style of planting shrubs, especially flowering ones, and the use of buildings to add diversity to the landscape. His theories were presented as though they were the tastes of the Chinese.

Angular rocks can be dynamic; these also reflect the shape of the native fir trees that surround this dry garden designed by Terry Welch in Seattle, Washington.

Japanese gardens were also seen through a haze of preconceptions about the luxuriant, sensual East. They were considered to be as highly artificial as Chinese ones, but while Chambers believed that a careful use of artifice enhanced a garden, Japanese gardens were often described as mannered and affected. In other fields of art, Japanese styles did not produce such doubtful reactions. Once Japan began to open her doors, more screens, fans, silks and wood-block prints than ever were exported to the West, with an immediate effect on artists and other people. While painters experimented with unfamiliar Japanese techniques, shops started catering to the taste of the British and French for exotic objets dart. In 1875, Arthur Lasenby Liberty launched his first shop in London selling Japanese silks. Operas and operettas on Japanese themes soon appeared on the stage in London and Paris, among them Camille Saint-Sans La Princesse jaune (1872) and Gilbert and Sullivans The Mikado (1885). Both of these made Japan a land of fantasy, though Gilbert actually visited a Japanese village at an exhibition in Knightsbridge about the time The Mikado went into rehearsal. This village employed craftsmen, dancers, musicians and acrobats brought over from Japan; there was also a tea house and a garden with serving maidens whom Gilbert photographed.

Images of Japan

The theatre had a growing pool of sources to draw on. Many travel books were published between 1870 and 1890, recording the experiences of the first intrepid visitors. Novels soon followed, often romantic tales about Japanese women and western men, set in a decadent, sensual Japan. Pierre Lotis Madame Chrysanthme (1888), based on his experiences as a naval officer in Nagasaki, was made into an opera by Andr Messager in 1893, and both forms had some influence on Giacomo Puccini when he came to compose Madame Butterfly (1904). Lotis central character arrives in Japan expecting to see tiny paper houses surrounded by flowers and green gardens. Though he thinks nothing of this culture, he looks forward to seeing his ideas of Japan realized, but after some time there his prejudices turn into a deep dislike for what he interprets as Japanese artificiality. Lotis novel helped to spread the image of miniature gardens with misshapen pine-trees, diminutive bridges and minute waterfalls a landscape inhabited by flitting, child-like women with butterfly sleeves, glimpsed beneath the curving eaves of a tea house.

Another popular western image of Japan was of a land smothered in flowers. At the end of the nineteenth century, one of the greatest hits on the London stage was a musical extravaganza called