Acknowledgments

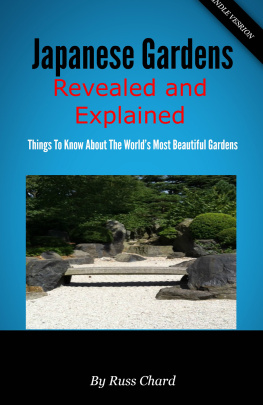

My greatest appreciation goes to all the gardeners who today continue to carry this centuries-old tradition of creating and maintaining some of the worlds most beautiful landscapes. The world owes thanks to all who labor to reshape the land into a piece of beautyfrom the early artists who created theory and design, to the humble many who stoop daily to gently nudge free a weed from the carpet of moss and who skillfully sculpt a shrub into an exquisite shape.

Marc Keanes book Japanese Garden Design is a masterful work that educates the reader about all the concepts that are integrated into a culture that has transformed this land as no other country has. His translation of Sakuteiki is essential to understanding the historical ideology behind Japanese gardens. I am most grateful to have his scholarship to refer to.

Terry J. Allen has lent her considerable editorial skills to bring precision and grace to abstract, aesthetic concepts. Her knowledge of Japanese culture complements her ability to glean and elucidate my thoughts and organize them into a most readable text.

I credit Allan Mandell with the phrase the art of seeing whereby the gardens become a guide to learning to understand the concepts of emptiness within harmony.

June Chong is the editorial supervisor who very patiently and gently herded these chapters into an impressive whole.

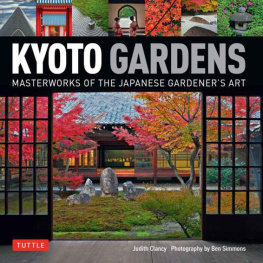

Lastly, the inspired photography of Ben Simmons presents the eternal beauty of Kyoto, and infuses it with a power and presence that is as genuine this century as it has been for millennia past. His eye is unerring in teaching the viewer what and how to see.

JUDITH CLANCY

It has been my great pleasure and good fortune to collaborate with Judith Clancy and Eric Oey for this special projectKyotos gardens are a unique treasure of concentrated beauty and spirit found nowhere else.

For their kindest support and invaluable assistance, I am indebted to June Chong, Chan Sow Yun, Terry J. Allen, Yuichi Kurakami, Yuri and Takuji Yanagisawa, Isamu Nishida, Tomoyo Yasuda, Yoko Yamada, Shiro Nakane, Mira Locher, Julia Nolet, Teiko Seki, Katharine Markulin and Koichi Hama, Kate Klippensteen, Barry Lancet, Robert Hancock, Takeshi Setogawa, Don Morton, Rumiko Honma, Naoto Ogo, Atsuro Komaki, Tomoko Minami, Hiroshi Tanaka, Mechtild Mertz, Karin Swanson, Machi Horie, Miyuki Ikeda, Masanobu Kanda, Toshifumi Owa, Kathryn Gremley, Marvin Jensen, Kraipit Phanvut, Dennis Bones Carpenter, Will Taylor, Richard Cheatham, Sarah and Greg Moon, Deborah and Vince Collier, Rebecca and Joe Stockwell, George McCarten, Bill and Julie Hope, Kenji Sakai, Shaun Heffernan, Sarah Auman, Yuki Hashimoto, Karen and Stan Andersen, Evon Streetman, Jerry Uelsmann, Bill and Pat Crosby, Sandy and Gary Jobe, Jay Phyfer, Rieko Matsumoto, Florinda Angeles, Ryoko Tsujimura, Yukie Suzuki, Reina Ogawa, Sonny and Rie Satoh, Robert Kulesh, Lourie Travis, Hans Krger, Noriko Yamaguchi, Kyoko Matsuda, Keiko Odani, Tatsuhiko and Rika Tanaka, Caroline Parsons, Pamela Pasti, Miwako Takagi, Thomas Ward, Wanrudee Buranakorn, Dom Giovannangeli, Kazuhiko Miki, Philip Rosenfeld, Ninomiya Takahashi, Fukuo Nagase, Natsuko Tanaka, Chiaki and Yoshihumi Nishida, and my friends at Myoren-ji. Heartfelt thanks to you all!

BEN SIMMONS/PHOTOGRAPHER

Bibliogaphy

Clancy, Judith, Exploring Kyoto , Stone Bridge Press, 2008

Keane, Marc P., Japanese Garden Design , Charles E. Tuttle, 1996

Keane, Marc P., Songs in the Garden, MKP Books, 2012

Kinoshita, June and Palevsky, Nicholas, Gateway to Japan, Kodansha, 1990

Mertz, Mechtild, Wood and Traditional Woodwork in Japan, Kaiseisha Press, 2011

Richie, Donald, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics , Stone Bridge Press, 2007

Takei, Jiro and Keane, Marc P., Sakuteiki, Visions of the Japanese Garden, Tuttle Publishing, 2001

Treb, Marc and Herman, Ron, The Guide to the Gardens of Kyoto, Shufunatomo, 1993

A winter seiyobou camellia comes into bloom beside Bashos hut in Konpuku-ji.

CHAPTER 1

Gardens of Central and Eastern Kyoto

At the very heart of Kyoto lies the former Imperial Palace. The emperors and courtiers who lived in the complex were subject not only to the vagaries of politics and intrigue, but to the dangers of fire and war. Each new court brought its own architectural and landscape design elements, but all were consistent with literary and artistic precepts, and most importantly, with the dictates of geomancy and ritual.

From the 6th century onward, geomancy was used to determine auspicious dates: when travelers might move or occasions should be scheduled, and even to decide the layout of a residence and, of course, its garden. The strictures included not only what physical demarcations would reshape and regulate the land, but also abstract superstitious constraints imported from China and Korea.

The divination of all these beliefs was complex and required consulting specialists, which the ritual-obsessed court did assiduously.

As the city took shape, the land was reconfigured to adhere to geomancy-determined rituals and beliefs. The system gave structure to personal lives and conferred a lasting legacy on the shape and spirit of Kyoto.

A flattopped cone of sand at Ginkaku-ji. Visitors to Kennin-ji. Inner gardens flank a corridor in Nanzen-ji. A young pine in the garden of Tenju-an. Waiting for inner stillness.

KYOTOS OLD IMPERIAL PALACE GARDEN

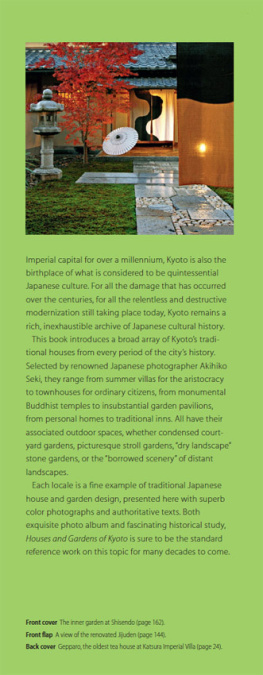

The city of Kyoto underwent an immense transition in 1868 when the imperial court was moved to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo (eastern capital). Only fifteen years earlier, Commodore Perrys black ships had opened the country to an array of Western thought and tastes that would infiltrate politics and the arts and spark deep transformations.

The old Imperial Palace and its gardens were not immune to change. The present complex was moved to Kyoto in 1788, but required considerable new construction after fire damage in 1855. Rather than an authentic reconstruction of the original buildings and gardens (better seen at Heian Shrine), the current grounds reflect an accumulation of traditional landscape concepts.

Garden views were an integral part of all but the most humble abodes, and even today, gardens provide highly desirable access to light and fresh air.

Nobles estates, conceived on a splendid scale, conjured grand scenery: Gardens echoed distant shorelines marked by jetting rock outlines and evoked cloud-shrouded mountain scenes depicted in ancient Chinese poetry and painting. The garden was a visual reinforcement of learned aesthetic concepts beloved by the court.

The old Imperial Palace gardens remain some of the countrys loveliest displays of landscape architecture. Their gardeners attract the best pupils of the art as well as the finest specimens of flora and rocks. Retaining its centuries-old design, the courtyard is a span of white, raked gravel that evokes the yuniwa (a sacred space) at shrines. Two flowering trees, a cherry and trifoliate orange, accent the quiet expanse. The area served as a site for religious ceremonies related to the court and was presided over by the emperor, once viewed as a divine descendant of the Sun Goddess. The limited grounds open to visitors are rich with moss, low sculpted pine and cedar, and other horticultural masterpieces.