Spaces in Translation

PENN STUDIES IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

John Dixon Hunt, Series Editor

This series is dedicated to the study and promotion of a wide variety of approaches to landscape architecture, with special emphasis on connections between theory and practice. It includes monographs on key topics in history and theory, descriptions of projects by both established and rising designers, translations of major foreign-language texts, anthologies of theoretical and historical writings on classic issues, and critical writing by members of the profession of landscape architecture.

The series was the recipient of the Award of Honor in Communications from the American Society of Landscape Architects, 2006.

Spaces in Translation

Japanese Gardens and the West

CHRISTIAN TAGSOLD

Copyright 2017 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tagsold, Christian, author.

Title: Spaces in translation : Japanese gardens and the West / Christian Tagsold.

Other titles: Penn studies in landscape architecture.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2017] | Series: Penn studies in landscape architecture

Identifiers: LCCN 2017005515 | ISBN 9780812246742

(hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Gardens, JapaneseEuropeHistory20th century. | Gardens, JapaneseNorth AmericaHistory20th century. | Gardens, JapaneseDesignPhilosophy.

Classification: LCC SB458 .T33 2017 | DDC

712/.60952dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005515

Contents

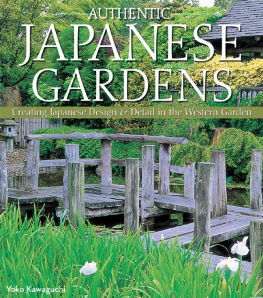

Japanese gardens are a global phenomenon, and nearly every major city in the world has at least one. We find them in New York, San Francisco, Berlin, London, and Paris and also in Buenos Aires, So Paulo, and Singapore. It is certainly not surprising that there are many Japanese gardens in Tokyo, Osaka, and especially Kyoto, and many tourists travel to Japan to visit them. However, the abundance of Japanese gardens around the globe might seem puzzling at first glance.

Why are Japanese gardens so popular? A search on the Internet produces among others the following interesting answer, on a website called Meditations on the Japanese Garden: The Japanese garden finds its main roots in an aesthetic that gives the garden an intrinsic value of its own, as a means of representing the natural world in an idealized state for contemplation, as a way of expressing the relationship that humans have to the natural world and its elements. Perhaps what most fascinates the Western viewer when first seeing photos of Japanese gardens, is that they seem to be paintings, using natural materials in three dimensional space.

This explanation is backed up by popular as well as scholarly literature. However, this statement creates more questions than answers. Surely contemplation and meditation are popular in the West. But perhaps the fact that Japanese gardens look like paintings is so fascinating to people because everyone desires one of his or her own? And would this not be true for Chinese gardens as well? In fact, in the eighteenth century, Chinese gardens were also described as picturesque, conducive to contemplation, and close to nature, much closer, in the minds of Enlightenment thinkers, than gardens in the artificial French or Italian styles. Yet in spite of these similarities, Japanese gardens massively outnumber their Chinese counterparts outside their

Why then, and under what circumstances, have Japanese gardens become so widespread? This question focuses on the process of their global dispersion and its history. Differences are obvious when comparing even just a few of the gardens. While New Yorks exemplar in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden is more than a hundred years old, the Japanese garden in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston was built three decades ago. Cologne, Germany, has two gardens to offer, one of which is about nine decades old while the other is some fifty years younger. Japanese gardens in the West have a history that stretches back about 150 years, and new ones are built each year.

These are just some of the central questions about Japanese gardens worldwide that are hard to answer simply by pointing out the gardens intrinsic qualities; many others could be asked. There was and probably is still a certain mystification involved in achieving this special global status for Japanese gardens. Until the last three decades most scholarly accounts of Japanese gardens reinforced the mystic qualities ascribed to them. While the first accounts of Japanese gardens at the end of the nineteenth century often had a very analytic point of view, romantic visions were also prominent. But even he lacked the theoretical tools for a more critical account. And in contrast to Lancaster, Western and Japanese authors alike more often than not offered interpretations resembling the earlier quote from the Internet. The popularity of this garden type was more mystifying than explainable.

Only in the last years have garden designers like Wybe Kuitert or specialists of East Asian art like Kendall H. Brown started to demystify some aspects of Japanese gardens. Behind this question was Yamadas confession that he himself was not convinced of the stone gardens beauty.

My personal opinion on Japanese gardens is a little bit different, but my uneasiness is nevertheless quite similar. I do enjoy visiting Japanese gardens, be it in New York, my hometown of Dsseldorf, or Kyoto. In that respect working on this book has been a wonderful experience. My research has led me to visit many public parks and gardens and to look for their Asian-inspired additions. I tried to obtain archival material concerning the gardens I wanted to use as examples: I have always wanted to know how the gardens feel and work as representational spaces. This has meant visiting about ninety Japanese gardens in ten countries over the years. In addition I asked friends around the world to send me information on gardens in their cities and countries. Finally, I read many papers dealing with individual Japanese gardens, or Japanese gardens in certain regions or countries, which helped complete the picture.

But the research has not only been about having fun and enjoying the gardens. I never accepted the commonplace and essentialist explanations for why people find them fascinating. Nor have I enjoyed how most of these gardens are presented to the public through informational boards and strict rules of use; it is as though the admonishing fingers of members of park commissions are trying to educate me, to remind me as a visitor all the time that these gardens are meant for meditation, that I am not free to enjoy them as I choose. Sometimes real-life guardians were in attendance and warned me not to step on pebbles or raise my voice beyond a whisperand this happened more than once. Ascribing special qualities to Japanese gardens not only has theoretical consequences; these qualities are sometimes enforced literally. Interestingly enough, the only time that garden attendants not only allowed but even urged me to step on the green beyond the path was in a garden in Fukuoka, Japan. This practical mystification of Japanese gardens added to my questions about them. Japanese gardens are not only objects of discourse. They are also very concrete spatial ensembles.