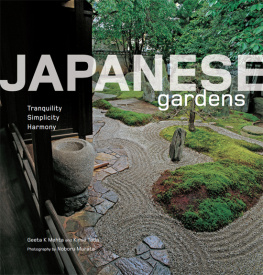

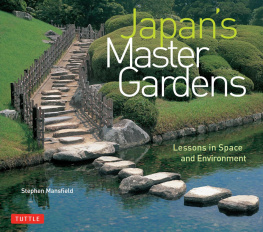

JAPANESE GARDENS

STEPHEN MANSFIELD

Preface

The title for this book was inspired by a fondness among Japanese artists, writers and the general public for compendiums of one hundred, celebrated examples being the twelfth century anthology One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, Utagawa Hiroshiges One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, Hokusais One Hundred Ghost Stories and, more recently, Fukada Kyuyas One Hundred Mountains of Japan. The Japan Environment Agency even went to the trouble of registering one hundred quintessentially Japanese sounds, from the tolling of a bronze bell in a fire tower to the cracking of ice floes in sub-Arctic Hokkaido and the flapping of crane wings in southern Kyushu, all in the hope that they could be preserved when the substance no longer exists.

The inaccuracy of ranking gardens according to their assumed merits, a method that is subjective at best, is obvious. While I have selected Japanese gardens as celebrated as the landscapes of Capability Brown or Humphry Repton, designs as imprinted on the collective mind as the geometric formalism of Vaux-le-Vicomte, there are also little visited gardens, works deserving of more attention.

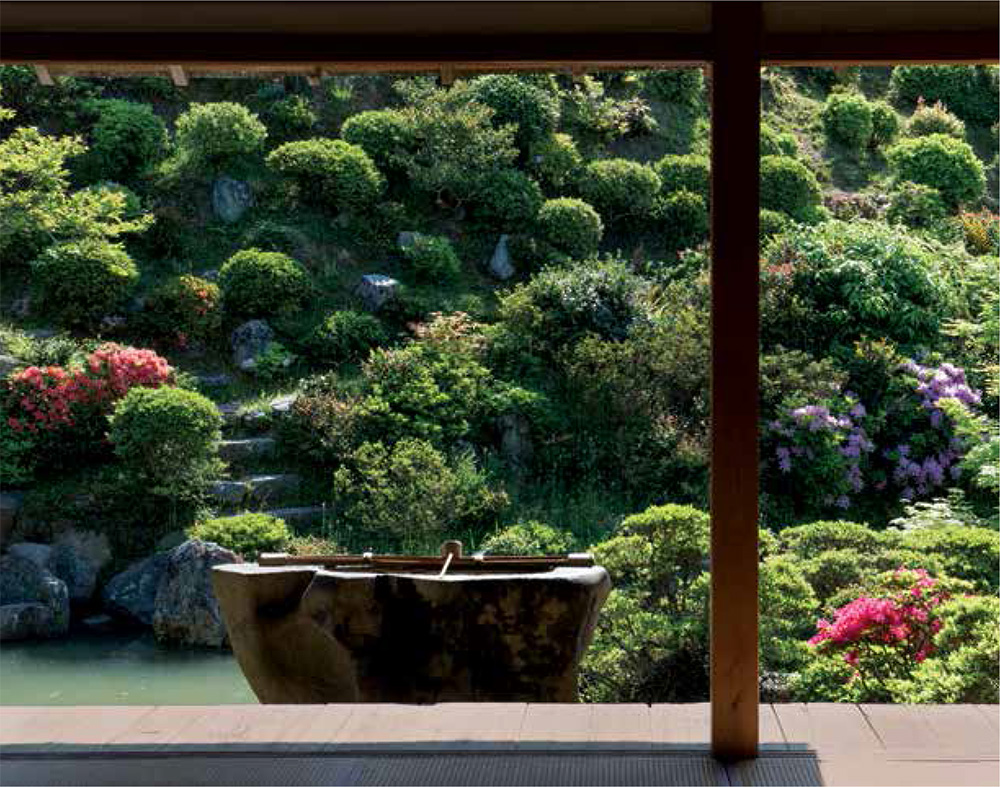

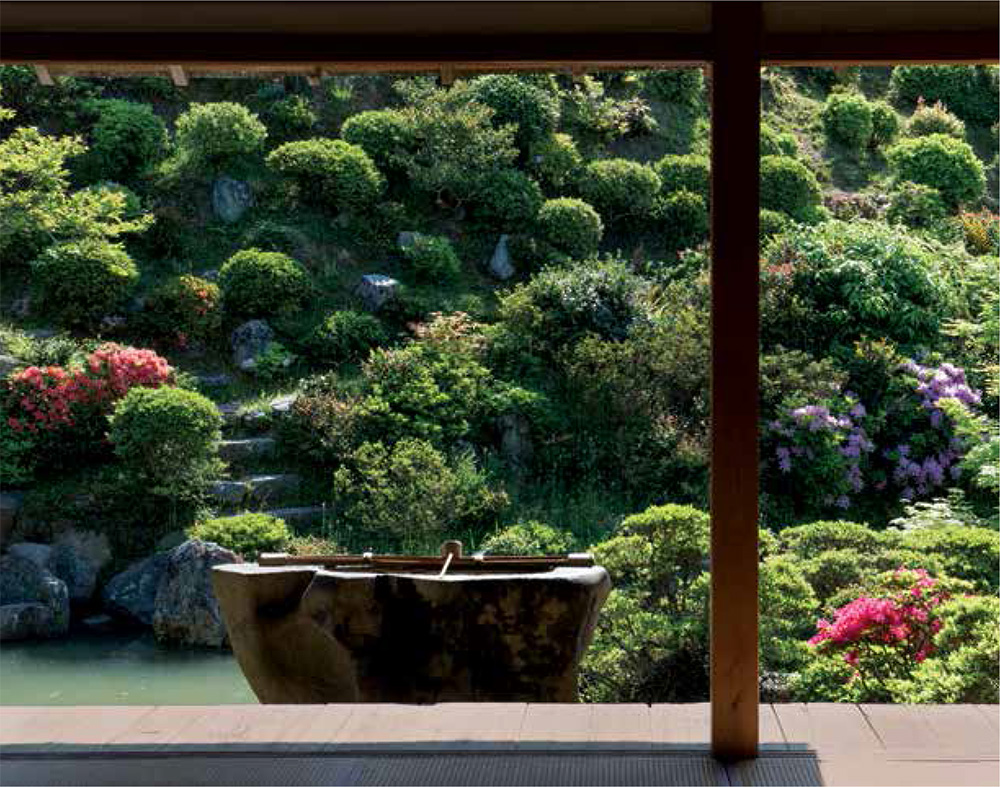

A garden perspective from the second floor of the Kiun-kaku residence.

The criteria for selecting these landscapes was how well they represented the various Japanese garden forms. Inevitably, these include stroll, stone, tea and courtyard gardens as well as works created for the early noble families of Edo (present-day Tokyo), imperial gardens, and later designs commissioned by wealthy entrepreneurs. There are a number of experimental, contemporary gardens that defy easy classification. The book also includes a small sampling of herbal and medicinal gardens and flower viewing sites. The book concludes with a set of images from Okinawa, where the Chinese influence on its private and royal gardens is strongly felt.

The rock groupings at Kongobun-ji Temple on Mount Koya represent authority rather than subtlety.

Not intended as a guide book per se, it can, nonetheless, be used as a selective guide to the gardens of Japan and as a sight companion to visiting wellknown locations. For obvious space reasons, some very fine gardens are not included here. Readers are encouraged to explore Japanese gardens beyond the confines of this numerically extensive but not finite book.

The gardens have been placed in cardinal clusters, the Kyoto and Tokyo groupings in an approximate north, south, east and west order, regional gardens starting in the sub-Arctic northern island of Hokkaido and terminating in the southernmost, sub-tropical region of Okinawa. Residents of large cities such as Osaka, Kobe or Kagoshima might not appreciate the term regional, with its implications of provinciality, but for my purposes this simply refers to gardens in places other than Kyoto and Tokyo.

As with all nature photography, a degree of patience is required to capture the right light, changing hues and climatic conditions. At other times, images almost seem to compose themselves. All the photographs in this book were taken on digital cameras. When processing and editing images, rather than attempting to super-enhance them I have tried to reproduce the same colors, tones and textural qualities seen with the eye. None of the compositions are cropped.

Entrance fees for the gardens have been ranked according to yen symbols:

= 600 or less

= 6001000

= Over 1000

Historical Periods

Nara 710795

Heian 7941185

Kamakura 11851333

Muromachi 13331568

Momoyama 15681600

Edo 16001868

Meiji 18681912

Taisho 19121926

Showa 19261989

Heisei 19892019

RIGHT The pond garden of Tenryu-ji, a living manifestation of Buddhist tenets.

Japans Incomparable Gardens

If Westerners occasionally see the hand of God in the slants of light piercing the tall, cathedral-like trees of their forests, the early Japanese, making clearings in their woodland glades, created actual places of worship.

Pre-Shinto and Buddhist natives of Japan, without shrines, temples or religious reliquaries, sought out features of the natural world as manifestations of divinity. Large rocks, known as iwakura, were placed in forest clearings, beside waterfalls and along stretches of pebbly beach. Conductors through which the gods could be petitioned, these natural altars and ritual spaces, characterized by a deliberate and aesthetically pleasing sculptural arrangement of stones, were not gardens in the strictest sense but they did prefigure the later centrality of rocks in Japanese landscape design.

The fringes of a pond skillfully planted with ferns, moss, grasses and other plants to soften the rocks and frame the pond.

When it became known that Chinese Taoists visualized paradise as a land mass known as the Islands of the Immortals, Japanese garden designers began to place rock arrangements symbolizing aspects of this mythology in their gardens, just as the Chinese had. When a Japanese emissary returned home in 607 with a detailed account of Chinese garden methods, Empress Suiko had a garden designed that was inspired by Mount Sumeru, the Buddhist center of the universe. The turtle and crane, Chinese symbols of longevity, were also incorporated into Japanese landscapes. One of the delights of visiting these gardens is trying to spot these forms, which are not always immediately visible.

This stone water laver at Chishaku-in adds foreground interest and stabilizes the framing of the garden.

By the Heian period, gardens had already begun to incorporate rock groupings, plant arrangements and islands understood by the literate as references to subjects found in both Chinese and Japanese literature. Symbolism came to be used not only to add depth and erudition to gardens but, through an unfolding of associations, to expand the spatial aspects of the mind.

Integral to the building process itself, it was entirely natural that gardeners should begin to integrate meanings into the design. A singular stone might be named Fudo-myoo, after the Buddhist divinity of fire; other groupings were set to evoke desolate mountain ranges and shorelines, or through their colors, tones and cardinal alignments to satisfy the demands of Chinese geomancy. In this way, primordial sculptural forms were imbued with sophisticated concepts whose provenance was both cultural and spiritual.

BELOW A wooden gate at Okochi Sanso hints at the gardens rustic aspirations.

The induction of Chinese geomantic principals and land patterns into Heian period garden designs, with their cognitive notions of interdependence, intuitive natural science and rational cosmology, are not easily grasped. But there was also a lighter, playful element in the early aristocratic and imperial gardens. Banquets, boating and poetry competitions took place within the precincts of these generously proportioned gardens. Stages set on small islands provided platforms for dance performances. Poetry competitions called

Next page