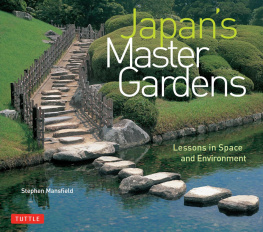

Japans

Master

Gardens

Lessons in Space

and Environment

Stephen Mansfield

TUTTLE Publishing

Tokyo | Rutland, Vermont | Singapore

Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Text copyright 2011 Stephen Mansfield

Photos copyright 2011 Stephen Mansfield

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mansfield, Stephen.

Japans master gardens: lessons in space and environment/Stephen Mansfield.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0852-3 (ebook)

1. Gardens, Japanese--History. 2. Gardens--Japan--Design--History. I. Title.

SB458.M36 2012

712.0952--dc23

2011019342

Distributed by

North America, Latin America & Europe

Tuttle Publishing, 364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 USA

Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993

info@tuttlepublishing.com; www.tuttlepublishing.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing, Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor

5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032

Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171, Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755

sales@tuttle.co.jp, www.tuttle.co.jp

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12, Singapore 534167 Tel: (65) 6280-1330, Fax: (65) 6280-6290

inquiries@periplus.com.sg; www.periplus.com

15 14 13 12 1111EP

5 4 3 2 1

Printed in Hong Kong

TUTTLE PUBLISHING is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

|

| contents |

|

|

|

chapter 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chapter 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chapter 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chapter 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chapter 5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PREFACE

Garden nature, like human nature, requires care and nurturing if it is not to lead to a kind of inanition.

Pondering the fate of the Japanese garden, the Meiji era writer Lafcadio Hearn wrote: These are the gardens of the past. The future will know them only as dreams, creations of a forgotten art. In this respect, thankfully, he was wrong.

How is it possible, though, to enjoy peace and tranquility, to savor Japanese gardens as healing, regenerative spaces when they have become so popular? Victims of their own success, whatever mystic or higher qualities they once had are at risk of being drowned out by the din of over-patronage. Japanese master gardens, however, may still offer alternative models for environmental enhancement. The purifying sensation one experiences on entering a garden affirms its power to promote a healthy emotional and spiritual life. In mirroring our yearning for stability and peace, our search for a settled place, its paths return us to our original nature.

In exploring the garden, we are making renewed contact with Japanese culture. Once we have understood one form, we may more readily appreciate another. In appropriating differing elements of Japanese culture, the Japanese garden prepares us for an examination of other arts and practices. Japanese aesthetics, the fine-tuning of taste, the development of connoisseurship through the appreciation of beauty, came later than the proto-gardens of the pre-Shinto era, but the transition from divine nature to art was relatively seamless. And yet, the revisualization of nature that takes place through the filtration of art in the Japanese garden is often quite different from what we are accustomed to. Disarmed, for example, by the vision of compositions purporting to be landscape works but made entirely of stone and gravel, we are forced to reconsider the place of nature in the garden, where appearances can be deceptive. The painter David Hockney, whose photomontages of the Ryoanji garden in Kyoto are playful reinterpretations of time and space, recognized this when he wrote: Surface is an illusion, but so is depth.

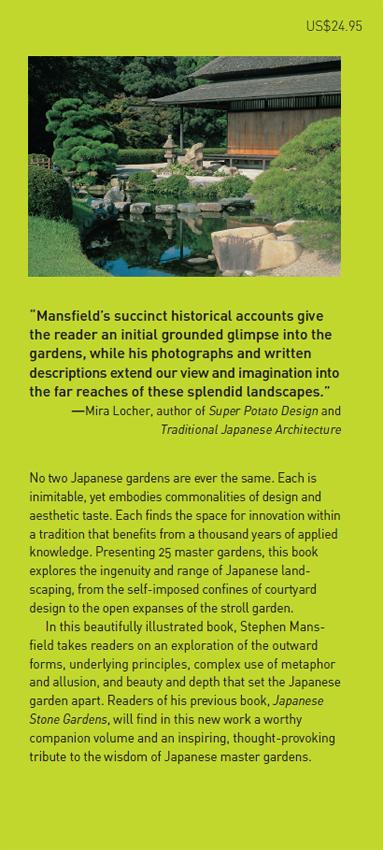

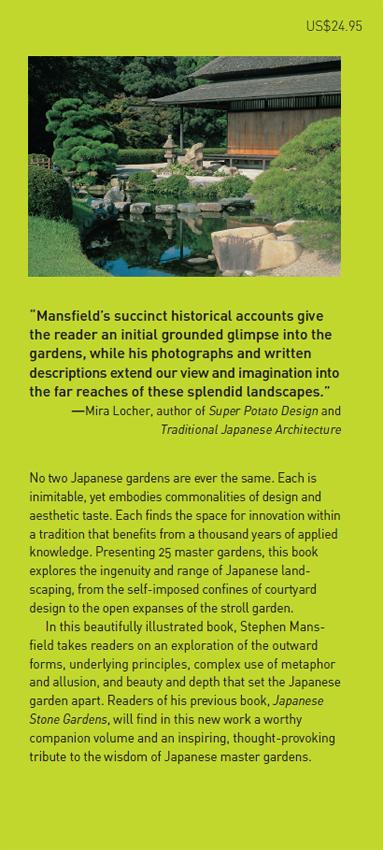

As a photographer, I am forced to view and analyze the Japanese garden through a lens. While shying away from discussing the variations in approach between Japanese and Western photographers, there do appear to be differences in the way their garden books are illustrated. It may be a case of suggestion and inference versus definition. When the light in a garden is flat, the Western photographer is apt to reject the image as dull, even lachrymose. Japanese photographers, on the other hand, who are masters of the tripod and long exposure, will exult in the muted tones. In this book, I have tried to steer a middle course, one that nonetheless instinctively embraces light that can turn gardens into scenes as radiant as stained glass.

In photographing these gardens, I opted to work with only 50 mm and 24 mm lenses, ones that closely conform to what the eye sees, and to use a very slow slide film, one that captures rather better the warmth and texture of gardens than the super-heated, manipulated colors of digital imagery.

So rich in detail are even the simplest of gardens that although we may never entirely comprehend their full meaning, we never tire of them; they can be visited time and again, always revealing something new. Preconceived, concisely framed, the Japanese garden may be an artifact but it reflects the dual characteristics of nature: vitality and serenity. In an age of hyper-materialism and excess, gardens offer an alternative vision. Restricted in space but boundless, transfixed in time yet temporal, the garden sanctuary, its changes as slow as those of a sundial, enables an unhurried contemplation of the beauty of the earth. In creating a state in which time is decelerated, gardens soothe our restlessness, freeing the mind from its habit of perpetual motion.

Sanctuaries have always been places where people retreat to find themselves, approach nature, their own gods. Here, we recognize that the gardens balanced, harmonious environs are similar to what we seek in our own lives. A point of departure, a confrontation with memory or the self, the garden is not a final destination. It occupies a transitional, intermediate space through which we pass, emerging rejuvenated, better able to cope. Gardens may not change our life, but they can improve it immeasurably.

Next page