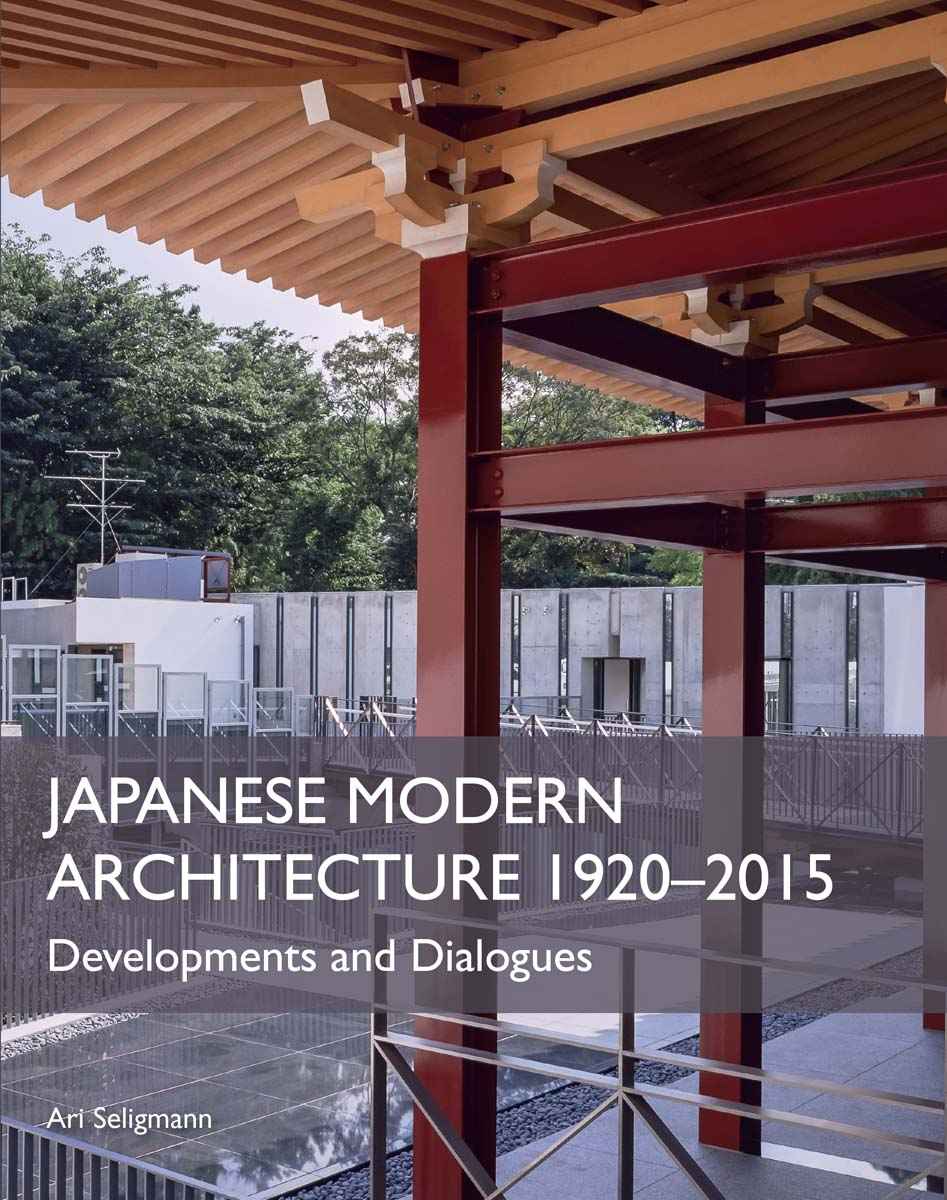

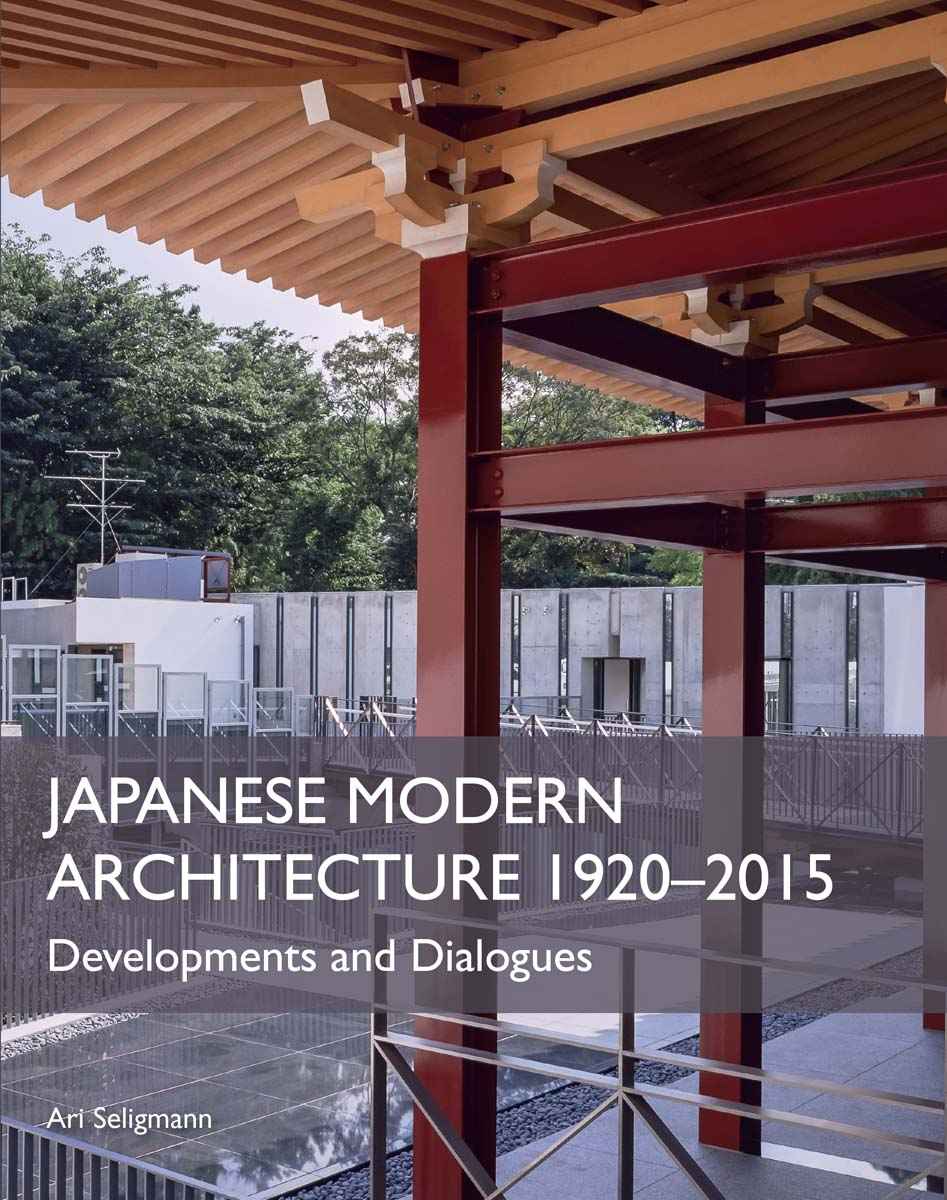

JAPANESE MODERN ARCHITECTURE 19202015

Developments and Dialogues

Ari Seligmann

First published in 2016 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

Ari Seligmann 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 249 6

Frontispiece: Umbrella House interior. (Courtesy of Shinichi Okuyama, photo by Osamu Murai)

Contents

Acknowledgements

L IKE ARCHITECTURE, PUBLICATIONS RESULT from multiple contributions and influences that are too voluminous to acknowledge individually. Therefore, I have elected to recognize some general clusters encompassing diverse people and a few select individuals. Without them all, the book would not have been possible. I would like to thank Crowood for the invitation and opportunity to prepare this book, which emerges from over twenty-five years of engagement with Japanese architecture as a designer, a historian and a critic. I am grateful to the broad range of architects and scholars who have influenced my approaches and understandings over the years. I am particularly indebted to Richard Wilson for helping me find this path and to Terunobu Fujimori for continually providing support in the journey along it. I am also grateful to David Stewart, Botond Bognar, Jonathan Reynolds and Ken Oshima, who sowed seeds for the fertile field of English-language scholarship on Japanese architectural developments. I am most appreciative of the vital contributions of all the architects and their offices: they provided content as well as context for illuminating the rich panoply of architectural developments. I am particularly grateful to Itsuko Hasegawa, Toyo Ito and Ryoji Suzuki for their continued support and influence. I would also like to acknowledge all of the architectural photographers, who play a critical role in how we see Japanese architecture. Most importantly, words cannot express my appreciation of my partner Shimako Iwasaki and her unwavering support. Finally, I am sincerely thankful for the academic and financial support provided by the Monash University Faculty of Art Design and Architecture, and for the efforts of my Japan Project students at Monash, who helped formalize the synoptic diagrams within this volume and were a sounding board for the book. I sincerely hope that it will resonate and contribute to further dialogues on Japanese architecture.

Introduction

T HIS BOOK TRACES ALMOST 100 YEARS OF architectural production, outlining and exemplifying ongoing issues and concerns influencing architecture in Japan. Setting a context for subsequent considerations, the introduction examines the key categories composing the title and articulates the aims of the book. The following identifies aspects of Japanese and modern that combine in the construction and curation of Japanese modern architecture.

What Constitutes Japanese Architecture?

Is Japanese architecture something from the built environment of Japan? Is it a building designed by someone born in Japan or to Japanese parents regardless of location? Is it composed of projects that represent national identities or ideals? Does it represent particular techniques or sensibilities? While Japanese architecture may include all of these, and more, with increasing globalization and transnational exchanges simple national, ethnic and geographical categorizations have become increasingly complicated.

Although the contemporary contours of Japanese architecture may be less clear, the origin of architecture in Japan can be clearly identified. Architecture began in Japan in the Meiji period (18681912) as a foreign practice intimately connected to modernization. The profession of architecture, which institutionalized a division between architect and builder/craftsmen, was established in 1876 when Josiah Conder, who was a government-sponsored oyatoi (honourable alien employee) from London, founded the Architecture Department within the Engineering School at Tokyo Imperial University. Conder had a large influence on shaping architecture in Japan. His multifaceted appointment involved imparting theories and skills to Japanese students to enable them to produce Western-style buildings and producing commemorative buildings for the government, concretizing the ideals of Meiji modernization in built form.

From the outset of institutionalizing architecture in Japan, information exchange and international study tours were important components providing firsthand access and platforms for incorporating global developments. Upon graduation in 1879, the first class of Western-trained Japanese architects received travelling scholarships from the government to go to Europe and advance their studies. For example, Kingo Tatsuno, who was the top student, went to study with Conders mentor Roger Smith at London University and worked for William Burges. Tatsuno returned to Japan in 1883. In 1888 he embarked on a study tour of bank buildings in Brussels, New York, Chicago, London and Paris in preparation for the Bank of Japan in Nihonbashi (1896), as well as subsequent bank branches in Osaka, Kyoto, Nagoya, Kanazawa, Hakodate and Hiroshima. Dallas Finn, an expert on Meiji architecture, upheld Tatsunos resulting Bank of Japan as the first important Western building designed by a Japanese architect. Western-style Imperial Household Museums in Nara (1894) and Kyoto (1895) as well as the Akasaka Detached Palace (1909) for Crown Prince Yoshihito (the Taisho Emperor).

A hundred years later, by the 1980s, international engagements with Western architectural developments had transformed into transnational dialogues and exchanges, leading Reyner Banham to note the Japanization of world architecture. Banham confirmed Japans global status as a fruitful source of alternatives propelling modern and postmodern architectural developments. Contemporaneous with Banhams claims and the 1980s peak of economic prosperity, there was a flood of international architects working in Japan and Japanese architects undertaking commissions across the world. All of the resulting projects can be considered Japanese architecture and fed the Japanization of architecture around the globe.

Narrowing the large volume of potential content, this book selectively brackets Japanese architecture, examining projects located within the Japanese archipelago designed by native Japanese architects. The volume edits out important works in Japan by Conder, Ende and Bockmann, Frank Lloyd Wright, Antonin Raymond, Klein Dytham, Herzog & DeMeuron, OMA and FOA, as well as valuable projects by Fumihiko Maki, Arata Isozaki, Kisho Kurokawa, Yoshio Taniguchi, Toyo Ito, SANAA, Shigeru Ban and Sou Fujimoto in other countries. The book focuses on constructions in the Japanese context, while recognizing that Japanese architecture is not a singular construct. Like Japanese culture, religion and cuisine, its architecture is a fluid hybrid of domestic and international influences and regional variations.