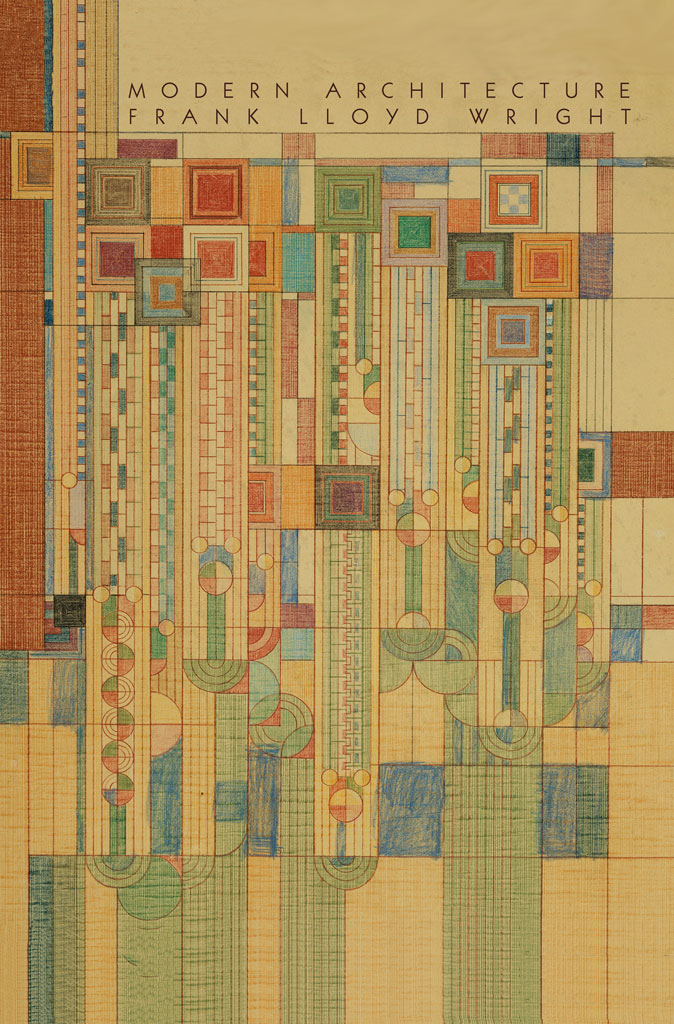

MODERN ARCHITECTURE

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

PRINCETON MONOGRAPHS IN ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY

MODERN ARCHITECTURE

BEING THE KAHN LECTURES FOR 1930

BY FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY NEIL LEVINE

PUBLISHED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF

ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF PRINCETON

UNIVERSITY

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 1931 Princeton University Press

Copyright renewed 1959 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

New introduction Copyright 2008 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

First published, 1931

Facsimile edition, with a new introduction by Neil Levine, 2008

Library of Congress Control Number 2007940601

ISBN 978-0-691-12937-2

eISBN 978-0-69123-253-9 (ebook)

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

press.princeton.edu

R0

DEDICATED TO YOUNG MEN IN ARCHITECTURE-F.L.W.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

PREFACE

1: MACHINERY, MATERIALS AND MEN

2: STYLE IN INDUSTRY

3: THE PASSING OF THE CORNICE

4: THE CARDBOARD HOUSE

5: THE TYRANNY OF THE SKYSCRAPER

6: THE CITY

INTRODUCTION

NEIL LEVINE

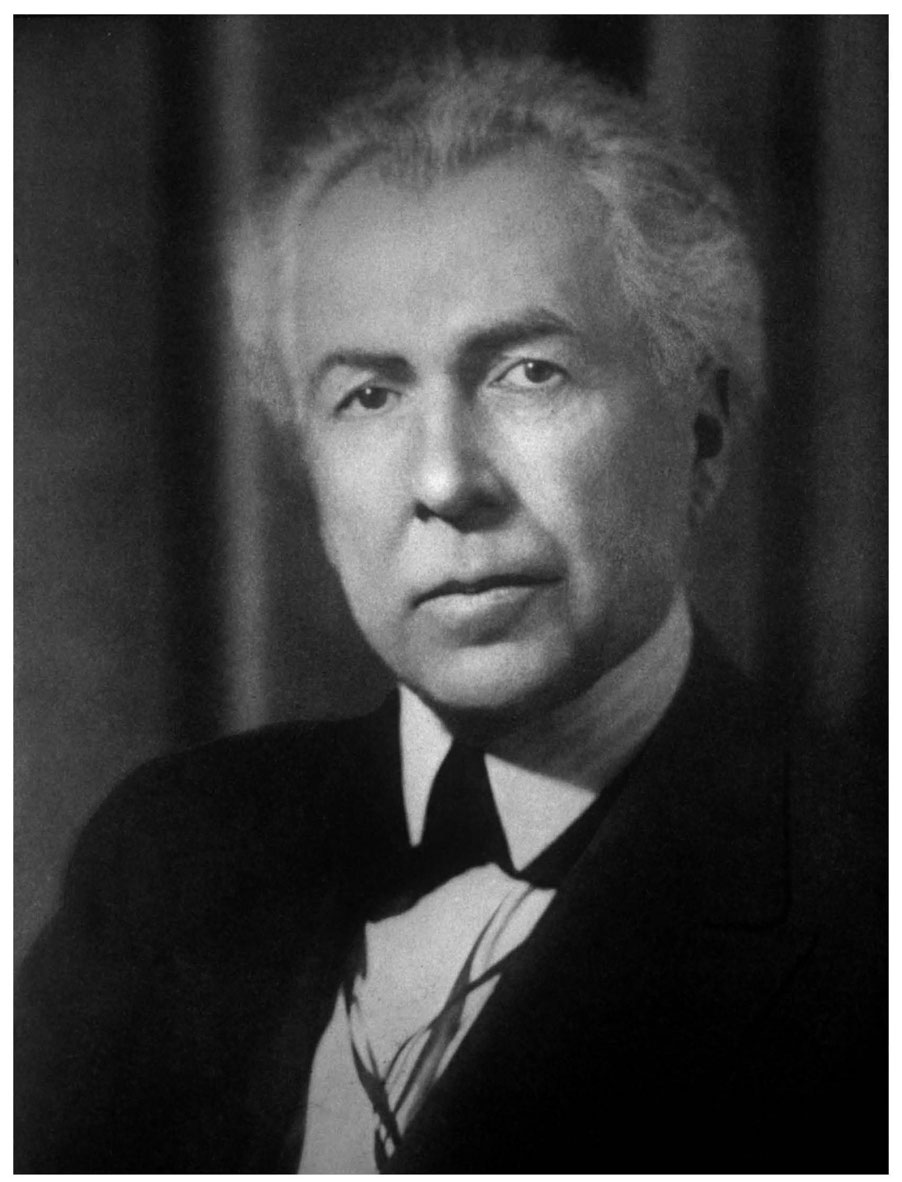

In a review in the New Republic in July 1931, just three months after Frank Lloyd Wrights Modern Architecture: Being the Kahn Lectures for 1930 was originally published, the brilliant young critic and early devotee of European modern architecture Catherine Bauer described it as the very best book on modern architecture that exists. A future leader in social housing and community planning, Bauer wrote this neither out of ignorance of the field nor out of personal sympathy with the authors position in it. She had spent the year 1926-27 and the summer and early fall of 1930 in Europe, where she met many of the important figures in the modern movement and studied the work being done. Ernst May and J.J.P. Oud, both deeply engaged in the area of housing, along with her mentor and lover Lewis Mumford, whom she met in 1928, were particularly instrumental in shaping her thinking on the social and collective purposes of architecture.

Bauer began her review of the Wright book affirming her belief that architecture is intrinsically an unsatisfactory field of expression for the individual poet-genius. A new architecture, she continued, "depends primarily on the careful establishment and strict acceptance of an idiom that has its roots in the social and economic structure of the time. Acknowledging that Wright was without doubt the most brilliant individual architect of our time, she deplored the fact that he only wants to express his own personality and thus concluded in the reviews preamble that his way was not the way of the future. The future, she stated, lay in the hands of men like Oud in Holland, Gropius and Stam and May in Germany, who have worked to strip architecture to its essentials, [and] who have suppressed their differences in the interests of the unit and the

At this point, Bauer stopped and declared: So much for the convictions of the reviewer. . . . [Bauers ellipses] and then went on to exclaim: Exuberant, confessedly romantic, insistently individualistic, at times even florid and rhetorical, [this book] is still (and I say it, who fought my rising enthusiasm at every turn of a page) the very best book on modern architecture that exists. After summarizing and analyzing its contents, she finally concluded:

I am, still, in active disagreement with about a third of the book. I still would really rather live in a workingmans house in Frankfurt [by Ernst May] than in one of Mr. Wrights handsome prairie mansions. I still believe that symbolic variations cannot be invented cold on a drafting board, that they must evolve in time out of the functional forms themselves or not at all. But, fundamental as this criticism may sound, it detracts very little from my perplexing enthusiasm. . . . [Parts of this book are] so rich in sound observation, trenchant comment and philosophic purity that architecture itself takes on a new dignity, a fresh social importance. And Frank Lloyd Wright emerges as one of the most interesting figures that America has yet

In its exceedingly direct and honest assessment, Bauers review reveals both the enormous significance of Wrights book as well as the complex and ambiguous status it bears in relation to the evolving history of modern architecture in what is usually considered to be its heroic stage.

Culminating a period of intense development and radical change since the beginning of the century, four books were published in English between 1929 and 1932 under the general title Modern Architecture. The one by the German architect Bruno Taut attempted to explain the "principles of the new movement mainly through its production on the European continent and under the influence of the new material, social, and economic conditions of the industrial The other three texts all carried subtitles. The young architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcocks Modern Architecture: Romanticism and Reintegration, which also came out in 1929, was the first comprehensive historical account and analysis in English of the movement, locating its origins in the breakdown of the classical system in the later eighteenth century and the ensuing eclecticism and technological advances of the following

Hitchcock was also directly involved, along with Philip Johnson, Alfred Barr, and Lewis Mumford (who was assisted by Bauer) in the last of these books to appear, Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, which served as the catalogue for the show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that took place in the early months of 1932 and that introduced the American audience to the architecture that the authors referred to as the International Style. Intending neither to trace the history of the movement nor to outline its social and industrial sources or implications, the exhibition catalogue focused on the formal characteristics that defined modern architecture as a genuinely new style. One of the architects given a featured place in the exhibition, along with Oud, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier, was their architectural uncle Frank Lloyd Wright. This was not, as Barr wrote, because he is intimately related to the Style nor merely a pioneer ancestor," but because, as a passionately independent genius whose career is a history of original discovery and contradiction, his work had to be seen as the embodiment of the romantic principle of individualism that remains a challenge to the classical austerity of the style of his younger

Wrights Modern Architecture appeared the year before the International Style exhibition. In its focus on the role of the individual in the creation of a spiritually liberated form of modern, democratic design along with its opposition of the idea of an organic architecture to one based on a collective machine aesthetic, Wrights book stands as his first major public pronouncement on the subject of how his architecture fits into the development of the modern movement. It is the first actual book he ever published and thus represents the beginning of a determined effort on his part to bring his views on modern architecture into the public domain, an effort that soon saw the appearance of An Autobiography and The Disappearing City (both 1932) followed by numerous other books over the next twenty-seven While laying out the groundwork for a conception of a modern architecture grounded in nature and eschewing the mechanistic and functionalistic stereotypes of the 'machine aesthetic, Wrights Modern Architecture also foreshadows the new world of decentralized living the architect was soon to call Broadacre City, a world that was to offer all the advantages of modern technology without any of the disadvantages of the urban congestion and blight that many recognized at the time as a major consequence of modernity.