As a scholar of gender and race, I have no business writing about Frank Lloyd Wright, the quintessential representative of dead white male architecture. I never had any ambition to do so, nor, before this project, had I thought much about his work. Like most people, I loved Fallingwater, but his other work did not interest me. Some of it I dont even like; I would be perfectly happy never to set foot in Wingspread again. And, from a scholarship perspective, is yet another book on Wrights work really necessary? What more is there to say?

Putting together the proposal for this book turned me around completely. After a disastrous experience at a small Catholic college, I was looking for new opportunities when a call for book proposals from Routledge, Taylor & Francis, came my way. The topic of their call was not in my wheelhouse, but, emboldened by said disastrous experience, I decided to offer a counter proposal. I heard nothing and figured that nothing would come of it.

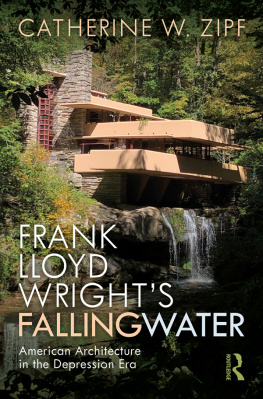

Six months later, however, I did hear back. The press did not want to pursue my proposal, but one piece of it had triggered their interestwould I care to submit a proposal for a book on Fallingwater? If so, might that book consider its Depression-era context? Yes, I was interested, and as I researched the proposal, I discovered to my surprise that precious few books had been written about Wrights Depression years. Most historians use the Depression to divide his career into early and later phases, thereby interrupting the story right in the middle. Further, no scholar had compared Wright to other architects of that era to fairly assess his level of productivity. Suddenly, this book became not only necessary but urgent. My sincerest thanks to Wendy Fuller and Genevieve Aoki of Routledge, Taylor & Francis, for their guidance in formulating the proposal and their assistance in its acceptance.

Our view of Wrights career as consisting of two phases, one before Fall-ingwater and one after, shields us from understanding how low he was in his career during the Depression years. Most textbooks teach that Wrights first career began with his early designs for the Ward Willits House, continued with the Robie House, and ended with Midway Gardens. Then, his second career picked up, maybe with the Hollyhock House but certainly with Fall-ingwater, and carried through to the Guggenheim. As I progressed through the scholarship, it was clear that most basic surveys simply didnt know how to handle the diversity or breadth of his work; he fits into too many places in the chronology. Nor did anyone really discuss those middle years, one or two scholars excepted.

In fact, those middle yearsthose years where the scholarship breaks continuitywere disastrous for Wright. After leaving his wife, Catherine, in 1909, his career vacillated from very high ups to very low downs. Up: building Taliesin and settling in with his new love, Mamah Borthwick (Cheney) to a new, albeit smaller, set of clients. Down: surviving Borthwicks murder by Wrights servant Julian Carlton, who burned Taliesin almost to the ground. Up: getting several new commissions in booming Los Angeles. Down: abandoning his work in Los Angeles and retreating to Taliesin with his mentally unstable second wife, Miriam Noel. Up: Writing a series of articles for Architectural Recorddesigned to attract new clients. Down: fleeing from Taliesin with his soon-to-be third wife, Olgivanna Hinzenberg, amid an outpouring of press drummed up by the said second wife, and then watching the bank foreclose on Taliesin because he could not pay his mortgage. And so on. At the time, it must have been difficult to see a scenario in which Wright could reemerge from this multi-year chaos. How did he do it? What path did he chart through the Depression specifically? What obstacles did he overcome to achieve success? As an architectural historian, these questions are among the first I ask about women and non-white architects, but it had never occurred to me that they also needed to be asked about Wright. Suddenly, this project fell squarely into my wheelhouse.

Digesting three very large bodies of scholarshipon Wright, on the Depression, and on the New Dealwas a challenge, to say the least. I am grateful to the scholars whose work helped me understand this enormously complex period in American history. I now consider you all to be my close friends (even those of you who are dead). To the Wright scholars in particular, I extend heartfelt thanks and my deepest appreciation for your work: Anthony Alofsin, H. Allen Brooks, Jeffrey Chusid, Richard Cleary, David De Long, Mary Jane Hamilton, Thomas Hines, Donald Hoffman, Donald Leslie Johnson, Paul Kruty, Neil Levine, Shirley du Fresne McArthur, Robert McCarter, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Terence Riley, Gail Satler, Robert Silman, Kathryn Smith, Paul Sprague, Franklin Toker, Robert Twombly, Lynda Waggoner, Robert Wojtowicz, and many others. Without your careful and thoughtful analyses, I would never have been able to complete this book.

The rise of this project occurred alongside the decline of my fathers health. I am so grateful to everyone at Routledge, Taylor & Francis, for their understanding and patience with the significant delays that caring for him caused. Special thanks go to Trudi Varcianna, Kalliope Dalto, Julia Pollacco, and Christine Bondira for their assistance in helping me set schedules that would still allow me to manage his needs.