Table of Contents

Remembering Ethel

I conceived a love of you quite beyond the ordinary relationship of client and Architect. That love gave you Fallingwater. You will never have anything more in your life like it.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT to Edgar Kaufmann

Make something, and die. IAN MCEWAN, Amsterdam

A FALLINGWATER TIMELINE

1909 E. J. Kaufmann discovers Bear Run; marries his cousin Liliane the same year.

1910 Kaufmann takes control of family department store in Pittsburgh; his son Edgar Junior born.

1916 Kaufmann rents Bear Run as a camp for his employees.

1926 Kaufmanns Department Store buys the 1,600 acres at Bear Run.

1933 Kaufmann seeks CCC status for Bear Run; when that fails, he buys the property in Lilianes name.

1934 E. J. proposes huge jobs in Pittsburgh to Frank Lloyd Wright; Edgar Junior goes to study with Wright at Taliesin; E. J. and Liliane follow; Kaufmann commissions Wright to build Fallingwater December 18.

1935 Edgar Junior leaves Wright; Wright conceives Fallingwater in July, draws it out September 22, presents drawings to family in Pittsburgh in October.

1936 Engineers caution Kaufmann not to build Fallingwater; working drawings ready by May; construction begins in June; Walter Hall joins as builder in July; cantilevers begin to crack.

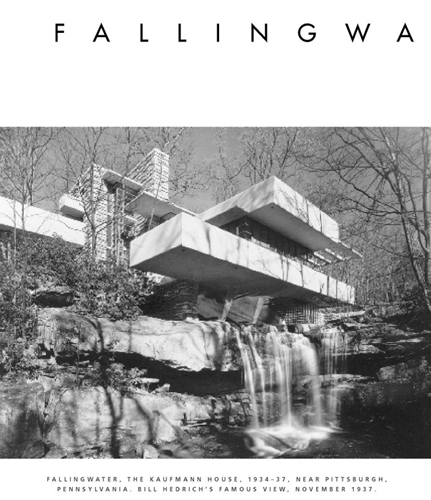

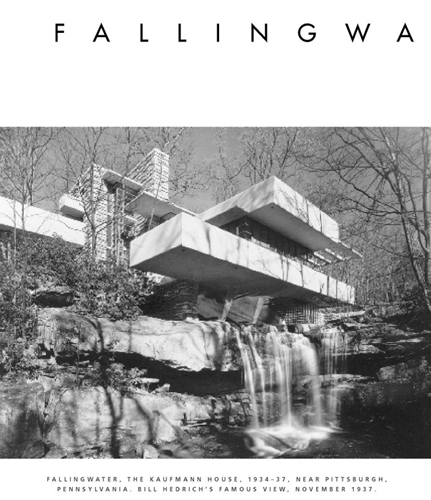

1937 Architectural Forum offers to publish Wrights new work; Bill Hedrich photographs Fallingwater in November; Kaufmanns occupy Fallingwater in December.

1938 Fallingwater featured at MoMA, in Architectural Forum, Time, and Life, in hundreds of newspapers and periodicals worldwide.

1939 Guesthouse added.

1952 Liliane dies; her tomb begins to rise at Bear Run the next year.

1955 E. J. Kaufmann dies.

1963 Edgar Kaufmann Jr. gives Fallingwater to Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

1989 Edgar Kaufmann Jr. dies.

1997 Engineers detect failure in the cantilevers; Fallingwater shored with steel girders.

2002 Post-tensioning restores cantilevers to health.

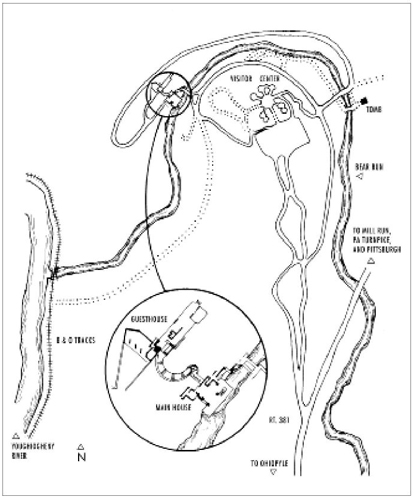

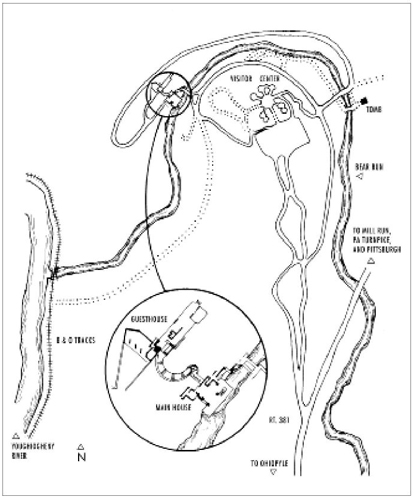

Fallingwater, with its approach bridge and the guesthouse further uphill

PROLOGUE

APPROACHING FALLING WATER

These two houses [Fallingwater and the Willey house] show Frank Lloyd Wright at the top of his powers, undoubtedly the worlds greatest living architect.

LEWIS MUMFORD, The New Yorker, 1938

Frank Lloyd Wright, the greatest architect of the 20th Century.

Time, 1938

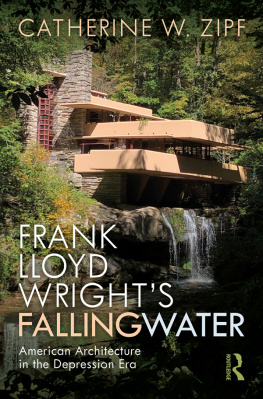

There are two ways of seeing, the seventeenth-century French painter Nicolas Poussin would always insist, with the eye and with the mind. We will need both those powerful instruments as we approach Frank Lloyd Wrights Fallingwater. Actually, you are already approaching Fallingwater in your mind. You probably recognize Wrights name, and quite possibly you have heard of Fallingwater, or would recognize it when shown a picture of a house perched over a waterfall. You may have encountered the description often applied to Fallingwater: unquestionably the most famous private residence ever built.

A monument of such fame beckons us to make a pilgrimage, which itself is a journey of the eye and of the mind. A pilgrim dreams half his life about visiting a site, then moves heaven and earth to get there. So even before setting out to western Pennsylvania, we can picture ourselves alongside the waterfall on the Bear Run stream. But we cannot flutter to Fallingwater like Tinkerbell: to begin with, there is no public transportation, which obliged one German student to hike the twenty-three miles from the nearest bus stop at Uniontown.

There is a second problem if we go by car, and that is aesthetic. Both the hour-long car trip from Pittsburgh and the passage of several hours from Washington, D.C., feature soothing hills but not much else to cheer about visually. A New Yorker may feel momentarily at home on seeing IRWIN GREENSBURG as the first Pennsylvania Turnpike exit east of Pittsburgh, but the sign proves to be shorthand for the two Revolutionary-era communities nearby: one founded by Colonel John Irwin, the other named for General Nathanael Greene. Southwestern Pennsylvania looks little changed from the hardscrabble country it was in the eighteenth century. Except for the Mellon holdings at Ligonier, this is deer-hunting country, not the foxhunting estates of old Virginia.

The honky-tonk that greets us at the turnpikes Donegal exit, nineteen miles north of Fallingwater, offers cultural dislocation of another sort. The first half-mile of local roadway brings us Exxon, Sunoco, BP, Hardees, Pizza Hut, Days Inn, Caddie Shak, vegetable stands, an artificial waterfall selling something, Eclipse Exotic Dancers (as the sign says), go-karts, astrologers, bingo, and Holistic Physical Therapy. The ammunition shops, ski rental huts, and chiropractic services lining our route arrange themselves in a near-perfect 1:1:1 ratio. The billboard-heralded Mountain Pines Resort turns out to be a vast and soggy trailer park, as we should have guessed.

Farther south, Routes 711 and 381 take us through a Pennsylvania Bible Belt: Baptist, United Methodist, Assembly of God, Church of God congregations, the County Line Church of the Brethren, and Stepping Stones Christian Bookstore, followed by the Normalville Rod & Gun Club. The billboards drop away somewhat when we reach the village of Mill Run, which serves as a gateway to Fallingwater. After a final pitch for Yogi Bears Jellystone Park, a GO IN PEACE sign sounds the first hopeful note in miles, and we get some decent views of nature on the margins of the Youghiogheny River valley. Fields look better tended here. Two more churches, then the woods thicken and the road dips down to a dwarf bridge that carries us over the stream called Bear Run. Signs discreetly inform us that it is time to turn for Fallingwater.

Fallingwater and other buildings at the Kaufmann estate of Bear Run

We enter darkly wooded grounds, drive a moment, halt at a ticket kiosk in the witty disguise of a Victorian outhouse, park the car, and park any children under the age of six at child care in the visitor center. For a minute or so we descend through a thicket of rhododendron via a stately wooden ramp into the perfect quiet of a lush glen. Alongside the ramp is the exposed sandstone wall of the ravine, its ledges recalling the photographs of Fallingwaters walls that hang in the visitor center. On the valley floor we encounter a forest of such virginal purity that we walk through it as though enchanted. Now the sound of Bear Run reaches us with almost oceanic intensity. A clearing in the woods reveals the stream, a concrete bridge, and a corner of Fallingwater.

In the old pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, the bedraggled faithful coming over the last Spanish hill would jostle one another to see who first could shout I see the towers! But our brother-pilgrims to Fallingwater hold back. Our first glimpse of the house brings us to a stop, and total silence.

Next page