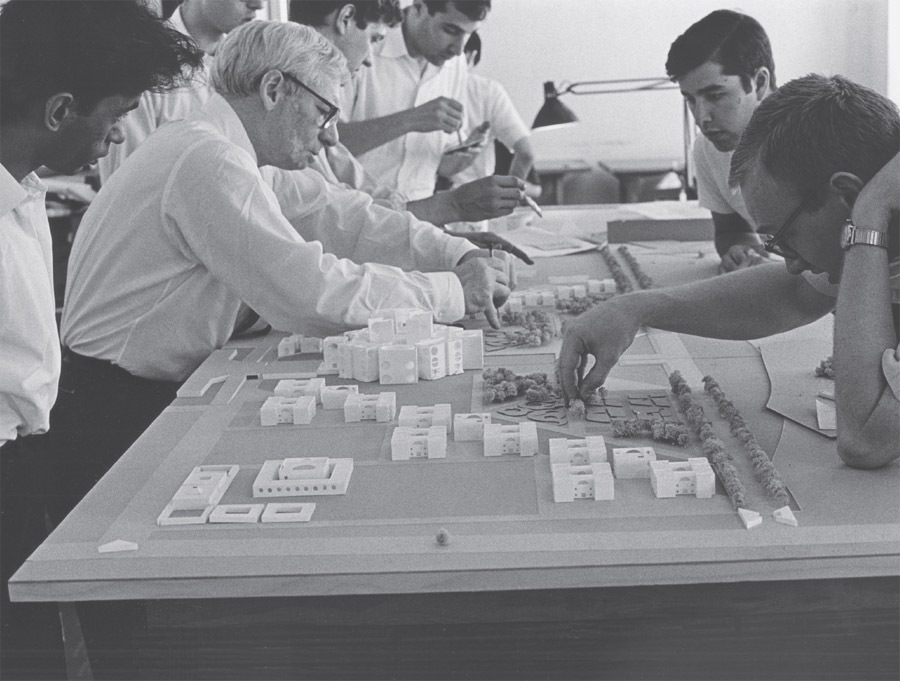

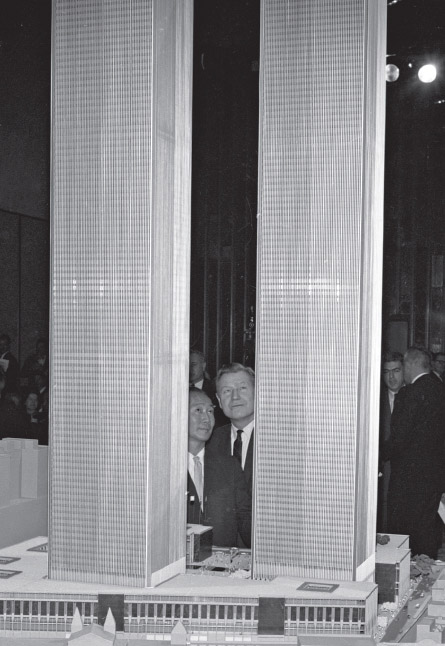

Louis Kahn and staff at work on a site model of the capitol building of Bangladesh, the Sher-e-Bangla Nagar of 19621983 in Dhaka, in his Philadelphia office, May 10, 1964. The most revered architectural educator of his time, he often used students to help develop his designs.

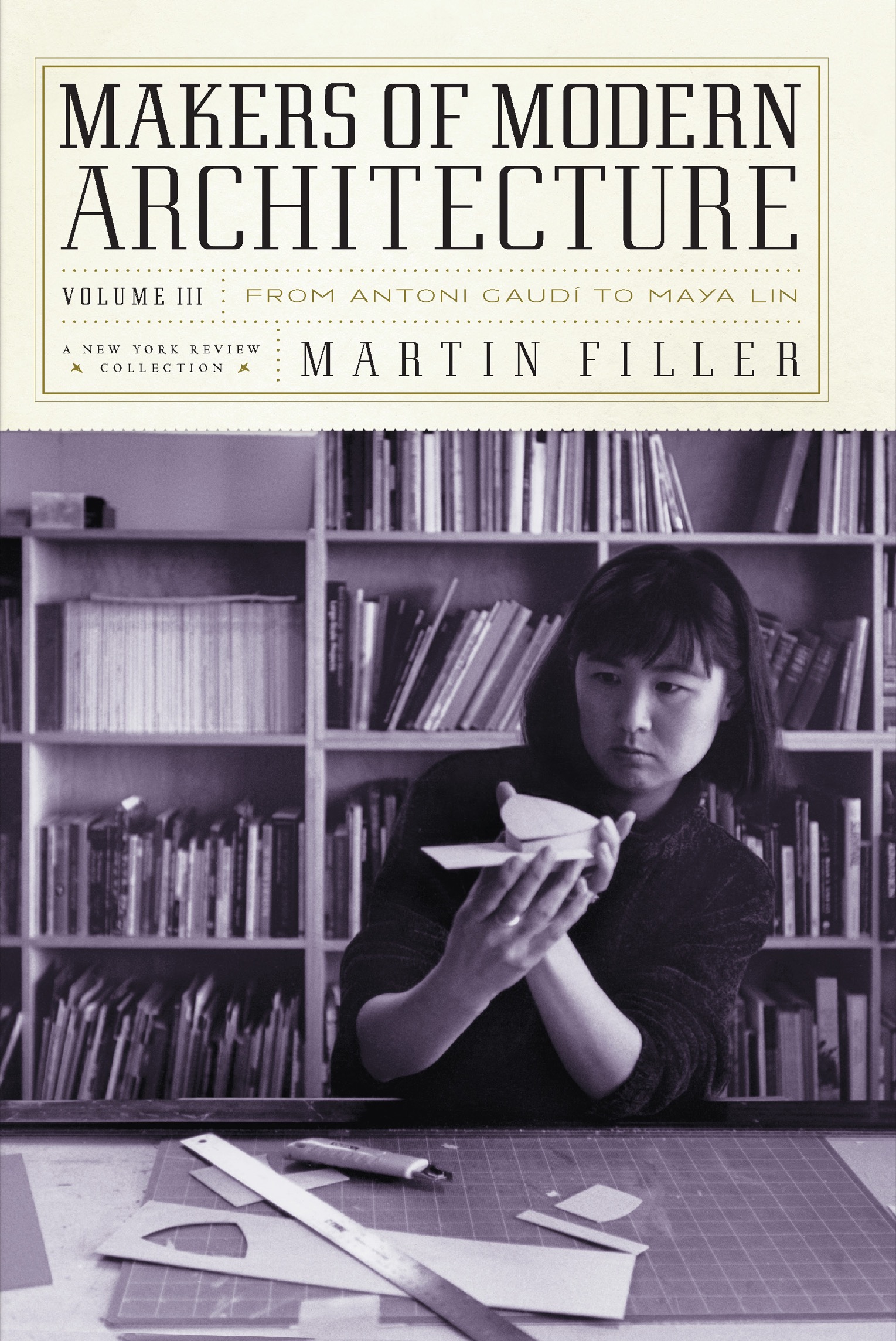

Makers of Modern Architecture

Volume III

Martin Filler

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

Publication of this book was made possible in part by a generous grant from Elise Jaffe + Jeffrey Brown.

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

MAKERS OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE VOLUME III

Copyright 2018 by Martin Filler

Copyright 2018 by NYREV, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Cover design: Louise Fili Ltd

Cover photo: Maya Lin, courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Filler, Martin, 1948

Makers of modern architecture / By Martin Filler.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59017-227-8 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-59017-227-2 (alk. paper)

1. Architecture, Modern 20th century. I. Title.

NA680.F46 2007

724'.6dc22

2007004176

ISBN 978-1-68137-303-4

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

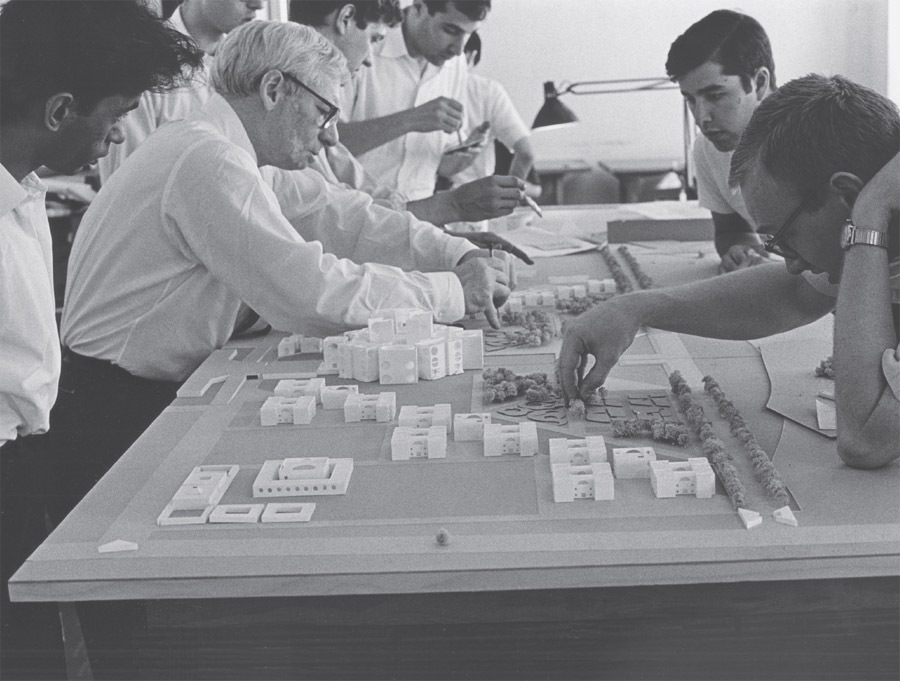

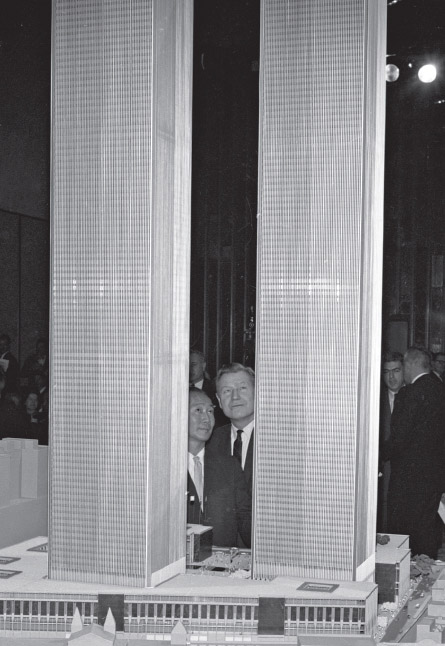

Governor Nelson Rockefeller looking at a model of the World Trade Center with its architect, Minoru Yamasaki, at the New York Hilton Hotel, Manhattan, January 19, 1964; photograph by John Campbell (New York Daily News/Getty Images)

Contents

Acknowledgments

THE DEATH OF Robert Silvers on March 20, 2017, at the age of eighty-seven, brought to an end the career of the greatest literary editor of modern times, and deprived me of the most important figure in my development as a writer. This third collection of my pieces for Bobfourteen of its nineteen chapters began as articles he commissioned and editedcontinues an idea he had in the 1980s when he suggested that I embark on a series of reassessments of major modern architects, both historical masters and contemporary practitioners, which could eventually be assembled into a book. Thus my Makers of Modern Architecture (2007) and Makers of Modern Architecture, Volume II (2013) came into being, and our thirty-two-year collaboration culminates with this collection.

Bobs work ethic was the stuff of literary legend. As many of my fellow New York Review contributors attested in the outpouring of tributes prompted by his death, Bobs fearsome mental acuity stayed astonishingly intact until the very end. Well into old age he could exhaust successive teams of young assistants during his prodigious weekend marathons, edit copy with flabbergasting speed and laser-like incisiveness, and come back to the office after a dinner party or a night at the opera and resume his labors until the small hours of the morning. But it was in the concluding weeks of his life that Bobs superhuman dedication to one all-consuming taskputting out the next issue (a total of 1,127 in his fifty-four years as editor)assumed heroic proportions. Early in 2017 he edited my last two pieces for him, on the redevelopment of New Yorks World Trade Center site (chapter 17) and, finally, Louis Kahn (chapter 10), even though he was emotionally shattered and very ill following his return to New York after the death in Switzerland of his beloved companion of four decades, Grace Dudley. This devoted couple now lie in Lausannes verdant Cimetire du Bois-de-Vaux.

A large part of Bobs genius stemmed from his ability to personalize the editorial process to a degree I have never experienced with anyone else. Employing a technique that I and others have likened to the patient/therapist transference in psychoanalysisan odd analogy, perhaps, given the amount of editorial space he gave over the years to one famously outspoken critic of FreudBob would patiently, expansively, and insightfully talk his contributors through the topic at hand (he knew a very great deal about everything) and draw from us thoughts we were not yet fully conscious that we held.

Those exhilarating consultations on a Sunday afternoonwhen I usually would hear from himrank among the peak experiences of my life. (My wife has said that she always knew when I was talking to Bob on the telephone because my voice went up one octave and I spoke very loudly.) But far from trying to impose his own point of view, Bob was intent on motivating us to think at our sharpest, write at our clearest, and produce what he knew could be our best, even if we were not so sure.

In time Bob became so synonymous with the Review that it was increasingly difficult to imagine its existence without him. The extent to which my colleagues shared this apprehension became clear to me at a gathering after his memorial at the New York Public Library, when a fellow contributor forlornly said to me, I dont know who to write for now. To my surprise I found myself instantly replying, Well, I do, because even though hes not going to be reading it, I will always write for Bob. This was the first realization Id had that what I call my Inner Bob did not depend on his being alive, and that I would be able to go on without him, wrenching though his death has been.

Rather than encouraging a personality cultdespite the intense devotion of his writerswhat now seems evident to me is that Bob methodically built an institution that would not only survive him but could thrive after he was gone if the high standards he set were maintained. Here principal credit must go to the Reviews publisher since 1984, Rea Hederman, whom Bob designated the executor of his estate, which added further to his burden as he steered the paper through an unprecedentedly difficult period, to say nothing of an even darker phase in our nations history.

However, the steadfastness Rea demonstrated throughout this dreaded transition came as no surprise to me, given the calm resolve he manifested in the five months following August 2014, when the Review and I were sued for libel by Zaha Hadid over an article in which I mistakenly claimed, because of a fact-checking lapse, that a large number of workers had died on the construction site of a project of hers that had not yet begun to be built, for which we quickly issued a retraction and an apology.

Throughout this difficult episode and the tsunami of unwelcome publicity it unleashed, Rea extended to me without hesitation the full legal representation of the Reviews law firm, Satterlee Stephens Burke & Burke. The partner in charge of our case, Mark A. Fowler, Esq., was a wise and judicious presence throughout, and a source of sound advice on matters large and small. (My friend and fellow writer Michael Z. Wise had gallantly offered to organize a legal defense fund on my behalf, but under the circumstances it was not needed.)

To Reas wife, Angela Hederman, I owe a debt of gratitude for her having suggested, in 2006, that a compendium of my essays from the preceding two decades would make a worthwhile addition to the New York Review Collections, published by New York Review Books. That imprints editor and the