THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

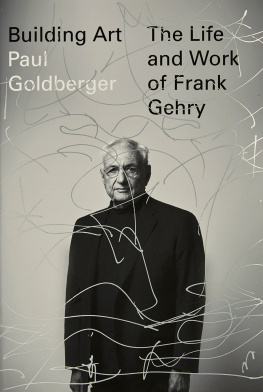

Copyright 2009 by Barbara Isenberg

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of the chapter Mixing It Up with Geniuses originally appeared in somewhat different form in Esquire.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Isenberg, Barbara (Barbara S.)

Conversations with Frank Gehry / Barbara Isenberg.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95972-0

1. Gehry, Frank O., 1929 Interviews. 2. ArchitectsUnited StatesInterviews.

I. Gehry, Frank O., 1929 II. Title.

NA 737. G 44 A 35 2009

720.92dc22 2008047616

v3.1

I never thought I was going to be who I am now. I never presumed anything.

FRANK GEHRY

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A few years ago, Frank Gehry was told he needed to have a brain scan, and he dutifully submitted to forty-five minutes in the cramped, claustrophobic confines of an MRI diagnostic chamber. As machines thumped and hammered, he slipped into himself and his imagination.

Afterward, the doctors had their MRI, which showed nothing unusual. Architect Gehry, on the other hand, had the preliminary design for the Louis Vuitton Foundation for Creation, a unique, glass-encased museum destined for the Bois de Boulogne in Paris. I focused on it the whole time I was in the machine, thinking about it, fantasizing and designing it, Gehry says. I retreat into my own world a lot when Im driving or in an airplane, too. My father used to call me a dreamer, which he didnt mean as a compliment, and he was right. He just underestimated the power of dreaming.

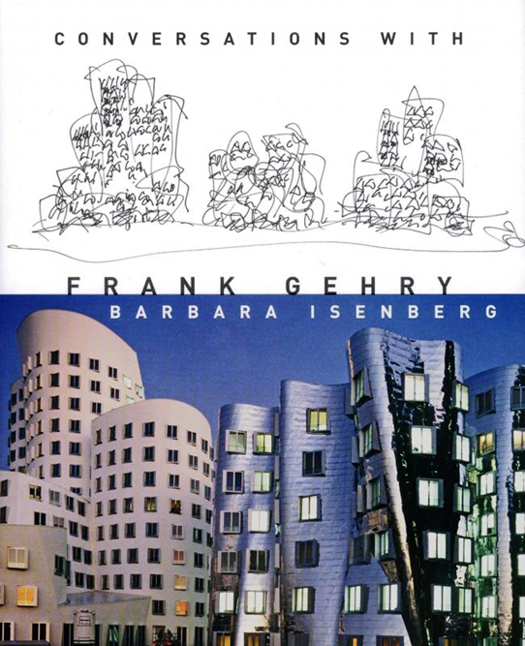

Gehrys preliminary design for the Louis Vuitton Foundation for Creation in Paris began life in an MRI diagnostic chamber. ()

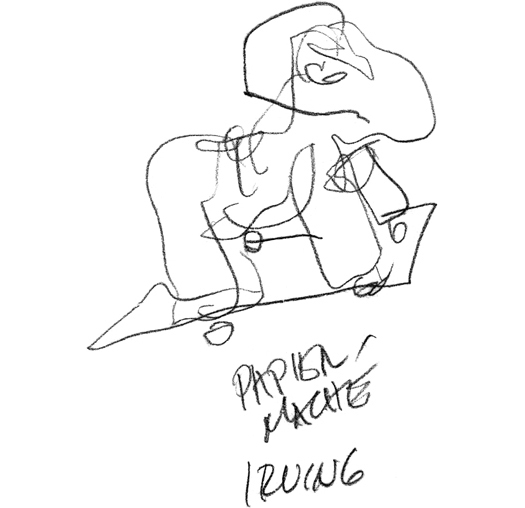

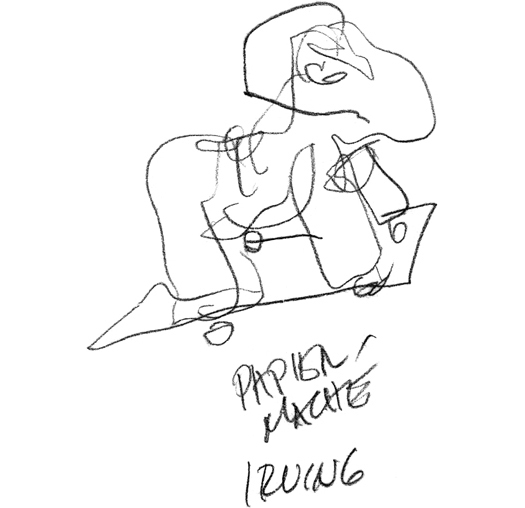

A Gehry drawing of a papier-mch hobbyhorse his father, Irving, once made ()

Few dreamers have so captured the publics imagination as Frank Gehry, widely considered among the most important and influential architects of his time. He has won dozens of awards from the American Institute of Architects alone, the coveted Pritzker Architecture Prize, the very first Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, his countrys National Medal of Arts, and innumerable international honors. His Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which led to that citys economic rebirth, has been called the worlds most celebrated new building by The New York Times, while the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles is similarly considered a visualand acousticmasterpiece. Projects from Las Vegas to Abu Dhabi are in design or development, under construction or preparing to open.

Ive written about many of those endeavors, interviewing Gehry again and again for newspapers, magazines, and books since the 1980s. A few years ago, he asked me if I would help him organize his memories through an oral history. I was immediately drawn to the idea, having enjoyed our many earlier interviews, and what began as an oral history soon evolved into the conversations Ive edited here. Since December 2004, Gehry and I have met regularly at his Los Angeles office and Santa Monica home, over restaurant breakfasts and conference room lunches. Weve talked about the family he was born into and the families he created, who he wanted to be and who he became, what architects do generally and what he does specifically, always coming back to the family, cultural, and geographic forces that have shaped his aesthetic.

Most of these talks have taken place at the worktable in his studio. At the far end of the table is usually a visual inventory of work most on his mind that day: a building model hes thinking about, a product prototype, perhaps a stack of construction photographs from an ongoing development. At an early visit, the table held a lightweight white paperlike lamp, which would later be called the Cloud. A possible wood container for the lamp appeared on the table a few weeks later, and soon came an elegant bracelet, harbinger of the Gehry Collection for Tiffanys. Another time, we took a break to look at a steel chair that wasnt quite finished; would I try sitting in it and tell him if it was comfortable?

We would sit at the near, uncluttered end of the worktable, with drawing paper and pen nearby. When Gehry talks, he draws. Our initial conversations about his childhood, for instance, were punctuated by breaks to draw such things as the papier-mch hobbyhorses his father made, the first Toronto neighborhood he remembers, the first house he lived in as a child. His is a visual memory, and the best way to describe where he grew up or a building he admires or even a building he designed is to re-create it in a sketch, not verbally.

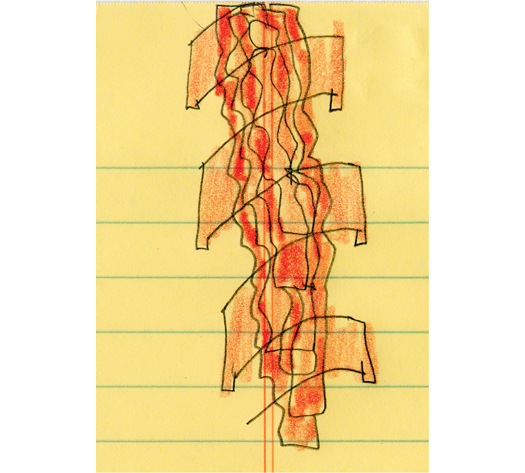

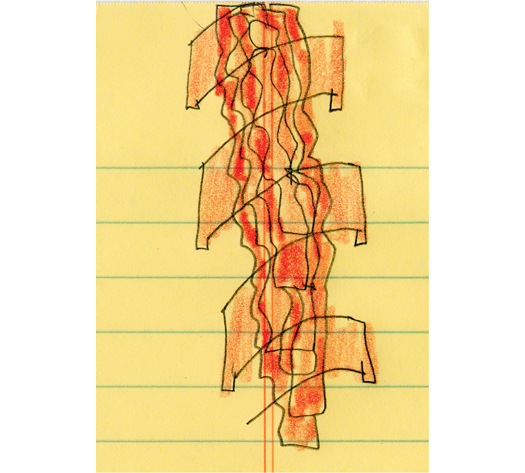

Gehry draws doodles while speaking on the phone. ()

He draws, too, when hes on the phone, making doodles on pages of the lined yellow pad he uses to take notes. Some he frames and gives to his wife, Berta, as presents. Others he stuffs in a drawer; at one visit, he opened a drawer of his desk and pulled out maybe two dozen pieces of yellow lined paper of various sizes, looked at them almost in wonder, and remarked, And thats just this week.

Sketchbooks follow him everywhere, including into the airplanes and hotel rooms he constantly inhabits. Gehry is almost childlike as he draws, concentrating intensely on something he so clearly enjoys. He is basically shy and occasionally seems awkwardand with large crowds, uneasyas people rush to meet him.

He is clearly most at home at Gehry Partners sprawling Los Angeles office complex. In a cavernous onetime industrial space, dozens of architects, designers, model makers, and other staff, mostly young, work on projects in various stages of development all over the world. The workplace is broken down by project, and as each grows or shrinks in terms of office time, so does the office space allotted to it. At one point, table after table was covered with models, photos, and plans for Atlantic Yards, his enormous redevelopment project in Brooklyn. And when design was most intense on expansion of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, models of it abounded in various scales.

Dozens of )

Gehry is both separate from and part of all that activity, working out of a semiprivate office with enough glass on three walls that he has an excellent view of what everyone else is doing. Windows slide open on two of those walls so he can talk with his executive assistant, Amy Achorn, on one side and his chief of staff, Meaghan Lloyd, on the other. Gehrys cell phone seems always at hand, usually just vibrating but sometimes ringing out Aaron Coplands Fanfare for the Common Man.